Macedonia and Greece: How they solved a 27-year name row

- Published

Thousands of protesters gathered late on Thursday to denounce the agreement with Macedonia

After years of talks and protests, Greece's parliament has backed a landmark deal to rename its neighbour the Republic of North Macedonia.

Despite its widespread unpopularity, MPs voted by a majority of seven in favour of the agreement, which has already been ratified by Macedonia.

Greeks have rejected Macedonia's name since its independence in 1991, because of their own region of the same name.

Polls suggest up to two-thirds of Greeks are unhappy with the deal.

There were clashes outside the parliament building the night before the vote as police fired tear gas to disperse protesters throwing flares and firecrackers.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Protesters displayed banners that declared "Macedonia is Greek" and inside parliament far-right Golden Dawn MPs shouted "traitors" as other MPs voted Yes.

Why did the deal take so long?

Macedonia has long existed as a northern region in Greece that includes second city Thessaloniki. Then along came a new nation, born out of the collapse of Yugoslavia, taking its name in 1991.

Greeks, fiercely proud of the ancient heritage of Alexander the Great and his father Philip II of Macedon, were infuriated and suspected their neighbour had territorial ambitions.

Police guarding the parliament building in Athens clashed with opponents of the Macedonia renaming plan

For years US diplomat Matthew Nimetz searched for common ground. Resolving the name was a big part of his job, as Greece thwarted its neighbour's bids to join Nato and the EU, and Macedonia retaliated.

Eventually governments changed and a new mood emerged, culminating in the deal signed on the banks of Lake Prespa in June 2018, external by Greek PM Alexis Tsipras and Macedonia's Zoran Zaev.

The two prime ministers (Mr Tsipras on the left) shook hands on the shores of Lake Prespa last June

Macedonians backed the deal, first in a September referendum in which only a third of voters took part and then in parliament.

Now that the deal has been backed by the Greek parliament, the Athens government will send its neighbour a verbal note and Macedonia will then inform the United Nations.

Mr Tsipras welcomed the new name shortly after parliament voted.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

For Macedonia itself, the name change will become final once Nato ambassadors have signed its accession in Brussels and the Greek parliament has then ratified that protocol.

What will change?

Under the historic Prespa agreement, everyone will have to use the new name.

The Republic of North Macedonia, or North Macedonia in short, will replace the existing title of Macedonia, which is formally called Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (or Fyrom) at the United Nations.

The language will continue to be known as Macedonian and its people known as Macedonians (citizens of the Republic of North Macedonia). In Macedonian the name will be Severna Makedonija. Greeks will know it as Voria Makedonia.

As well as backing its Nato accession, Greece will also be required to back its EU membership bid.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The two countries also agree:

"On the need to refrain from irredentism and revisionism in any form" - seen as dealing with Greek fears that the Macedonians might have designs on their territory

To tackle state propaganda and incitement and agree to set up an expert panel to consider an objective interpretation of history

"The terms 'Macedonia' and 'Macedonian' refer to a different historical context and cultural heritage" - and that one is Southern Slavic and not related to ancient Greece

The new Republic of North Macedonia will "review the status" of any public buildings or monuments that refer to ancient Greek history

Is the name-change unpopular?

Greeks broadly do not like it, with recent polls suggesting at least 60% are unhappy.

The Greek prime minister has lost his right-wing coalition partner, Independent Greeks, because of it. Mr Tsipras, who leads the left-wing Syriza party, is facing elections later this year.

Opposition New Democracy MP Giorgos Koumoutsakos said the deal ignored the majority of Greeks and was a "stab in the soul of the nation".

But the number of protesters recently has not been as big as in previous years, says Prof Dimitris Christopoulos of Panteion University, who backs the agreement.

Greek Orthodox clergy have been bitter opponents of the name change

"The rally's major political message that Macedonia is one and Greek is extremely nationalist," he says, unlike the mainstream opposition whose problem is recognising the language and nationality of their neighbours as Macedonian rather than North Macedonian.

For Macedonians it will be a question of getting used to a new name, and there is no love lost there either.

"We will have to work on our identity," says Prof Goran Janev of Sts Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje.

"Nobody can be happy about doing something because of blackmail by the international community. They allowed the Greek side for three decades to behave like spoilt brats."

Is the name row really about Alexander the Great?

Partly, yes.

Greece argues that Macedonia is an intrinsic part of Hellenic heritage, external. The ancient capital of Aigai is close to the modern Greek town of Vergina, while Alexander's birthplace is in Pella.

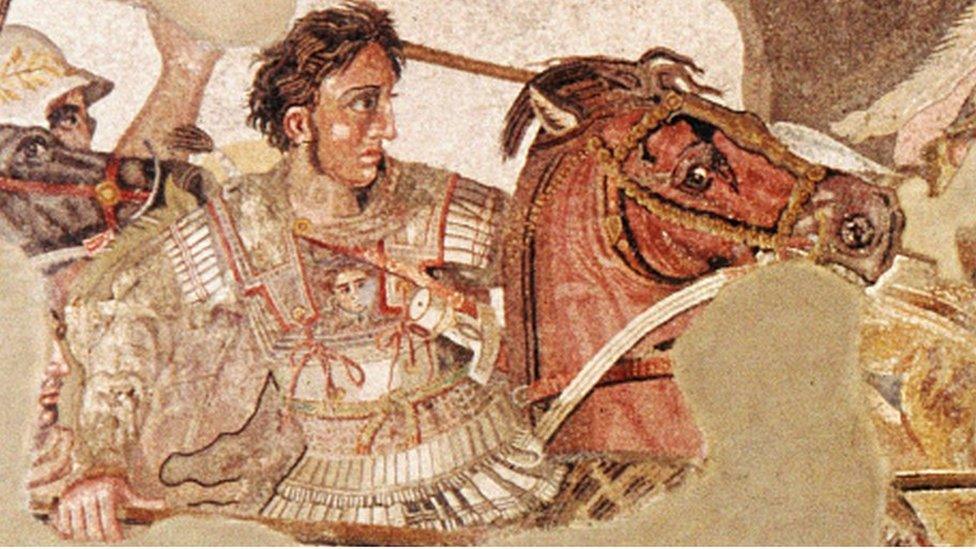

Alexander the Great ruled over Greece and created a vast empire in the ancient world

The new state of Macedonia did not help matters when it named the main airport in its capital, Skopje, after Ancient Greek hero Alexander the Great, as well as a key motorway running from the Serbian to the Greek border, which in Tito's Yugoslavia was known as the Brotherhood and Unity highway. An array of neo-classical buildings shot up, as Skopje sought a proud past.

That has stopped. The airport was renamed "International airport Skopje" last year, the Alexander the Great motorway is now simply "Friendship" (Prijatelstvo in Macedonian), and the buildings will be reviewed under the Prespa deal.

But while Alexander remains a powerful symbol, there are bitter memories from the more recent past.

When the Ottomans were driven out of the broad region known as Macedonia during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, it was split up, mainly between Greece and Serbia, but a small part went to Bulgaria.

In World War Two, Greek and Yugoslav Macedonia were occupied by Bulgaria, an ally of Nazi Germany and Italy. Communists from both Yugoslavia and Bulgaria played a part in the Greek civil war that followed.

Macedonians too remember the expulsion of tens of thousands of citizens after World War Two.

Is there much hope for the future?

Much of the agreement is about future co-operation - on road, rail, sea and by air - as well as in industry and tourism.

And much of that already goes on on both sides.

"The biggest investor in Macedonia, despite everything, is Greece so it's already there," says Dimitris Christopoulos. "The Greek banks are still the biggest investors there. So Macedonian Greece already have rational relations and this will accelerate.

One of the big ambitions of the deal is for the establishment within a month of a "Joint Inter-Disciplinary Committee of Experts" who will investigate whether school textbooks, maps and historical atlases need revising in both countries.

"It's difficult because we never had this truth and reconciliation processes. So many things were put under the carpet," says Prof Janev.

- Published8 February 2018

- Published30 August 2014