Macedonia referendum: PM vows to go ahead with name change

- Published

These young voters backed a Yes vote, holding up placards for a "European Macedonia"

Macedonia's Prime Minister Zoran Zaev has vowed to push ahead with plans to change the country's name to North Macedonia.

More than 90% backed the name change in a non-binding referendum on Sunday, but only a third of Macedonians took part, rendering it invalid.

The name change is aimed at ending a dispute with Greece, which has its own region called Macedonia.

To ratify the result, Mr Zaev needs the support of two-thirds of MPs.

What happens now?

Mr Zaev has threatened to call early elections if MPs do not support the proposal. He and his coalition partners will need at least a dozen opposition MPs to back the move.

"More than 90% of the total votes are 'Yes', so now it is parliament's turn to confirm the will of the majority," Mr Zaev told Agence France-Presse.

"I am determined to take Macedonia into the EU and Nato. It is time to support European Macedonia."

But opposition leaders claim the proposal to change the name failed. The leader of the main conservative opposition party, Hristijan Mickoski, told reporters the referendum was "deeply unsuccessful", and the government had "lost its legitimacy".

The Greek parliament must also give its approval for the change to go ahead, under a deal signed by Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and Mr Zaev in June.

What has the reaction been?

Athens had agreed to end its objections to Macedonia's EU and Nato membership bids if the change was passed.

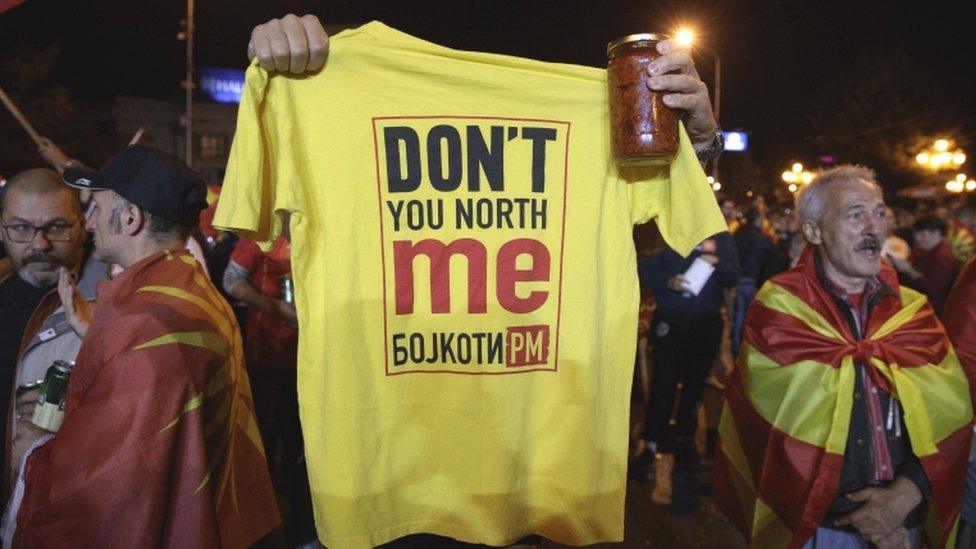

Opponents of the name change protest in Skopje

Mr Tsipras praised the "determination and courage" of Mr Zaev to "complete the implementation of this agreement", a government source said.

The European Union has called for all sides to respect the result. The EU's foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, said politicians must act "beyond party political lines".

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said on Twitter that the name change represented a "historic opportunity", adding: "Nato's door is open."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In Washington, the US state department urged Macedonia's lawmakers "to rise above partisan politics", and "secure a brighter future for the country as a full participant in Western institutions".

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said he hoped the situation would unfold "within the framework of the law".

Within the county, Macedonian opposition-leaning media outlets described the low turnout as a sign of the public's unwillingness to support the initiative, calling on Mr Zaev to resign.

Pro-government media have focused on the fact that the overwhelming majority of those who did vote supported the name change.

A victorious boycott?

Analysis by Guy Delauney, BBC Balkans correspondent

Adding the word "North" in front of "Macedonia" was never going to be simple. Now the issue has been plunged into a swirling vortex of complications.

All this has been ushered in by the somewhat surreal sight of people who had not even voted celebrating a victory. The campaigners to boycott the referendum had correctly worked out that the best way to undermine the agreement with Greece was not to vote against it, but stay away from the polls completely.

Some of this opposition was a heartfelt expression of the right to self-determination. But there was a large dollop of domestic politics, with the opposition VMRO-DPMNE party delighting in discomfiting Mr Zaev.

Now he faces the considerable challenge of finding a two-thirds majority in parliament to make constitutional changes. At least he has the support of Nato and the EU, both of which have urged Greece and Macedonia to press forward with ratification.

Why vote on a name change?

When Macedonia declared independence during the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, Greece objected to its new neighbour's name.

Present-day Macedonia and northern Greece were part of a Roman province called Macedonia. And both claim the heritage of Alexander the Great two centuries earlier.

Greece's objections forced the UN to refer to the new country as "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia".

Athens also vetoed Macedonia's attempt to join Nato in 2008 - and blocked its EU membership ambitions.

Prime Minister Zoran Zaev pushed for a Yes vote for a future in the EU and Nato

What was the proposed solution?

The addition of one word to Macedonia's constitutional name: North.

Since 1991, many suggestions have been proposed, then rejected.

But last year's change of government in Macedonia finally brought the start of serious negotiations.

- Published12 June 2018