Greek general election: Five things that swung the vote

- Published

Left-wing leader Alexis Tsipras (left) and centre-right leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis

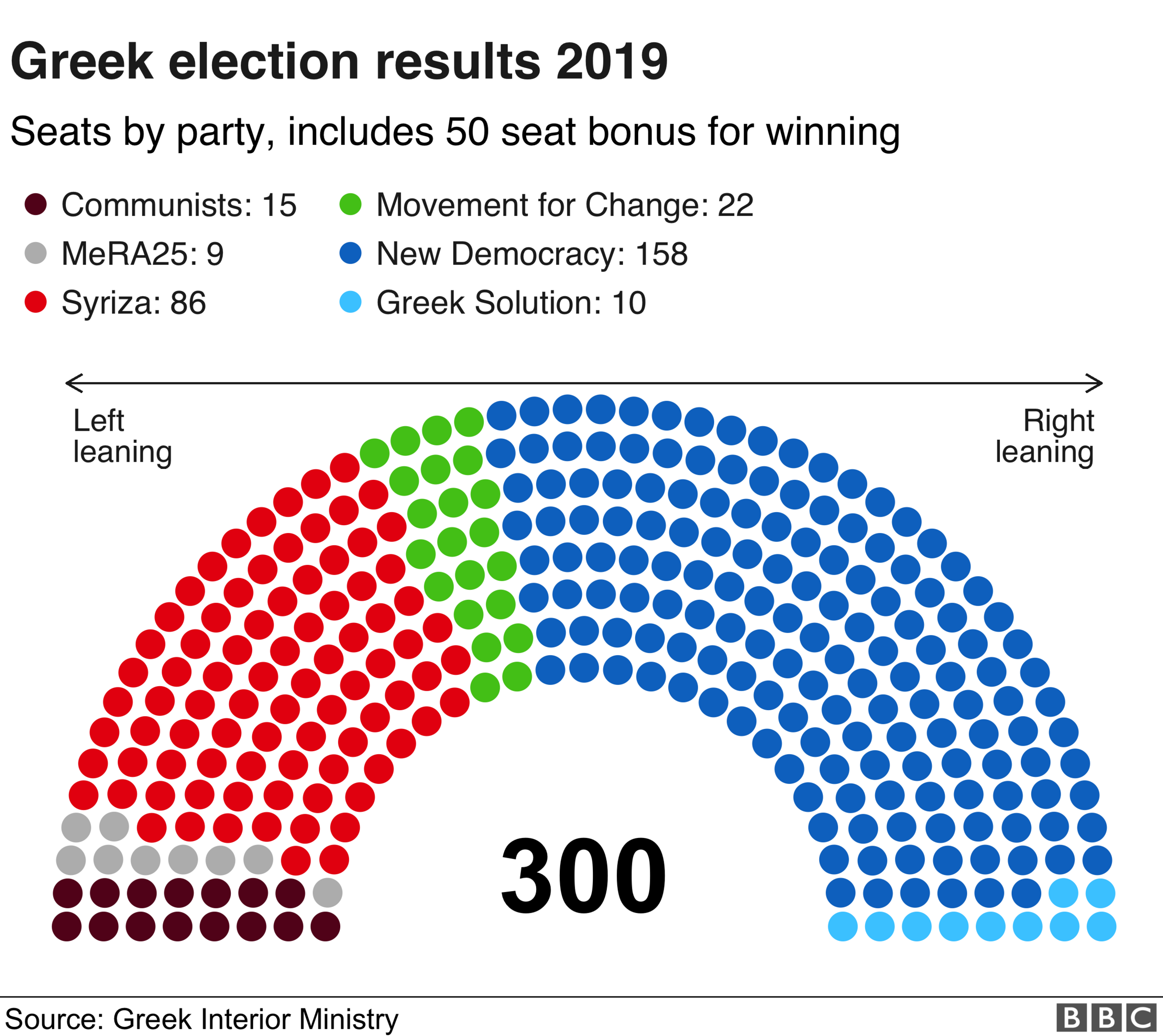

Greeks have elected a new centre-right prime minister, ending the premiership of left-wing Alexis Tsipras, who promised to end austerity back in 2015.

Following a convincing victory on Sunday, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis of the conservative New Democracy (ND) party said he would not fail to "honour the hopes" of the Greek people, and vowed his country would "proudly raise its head again".

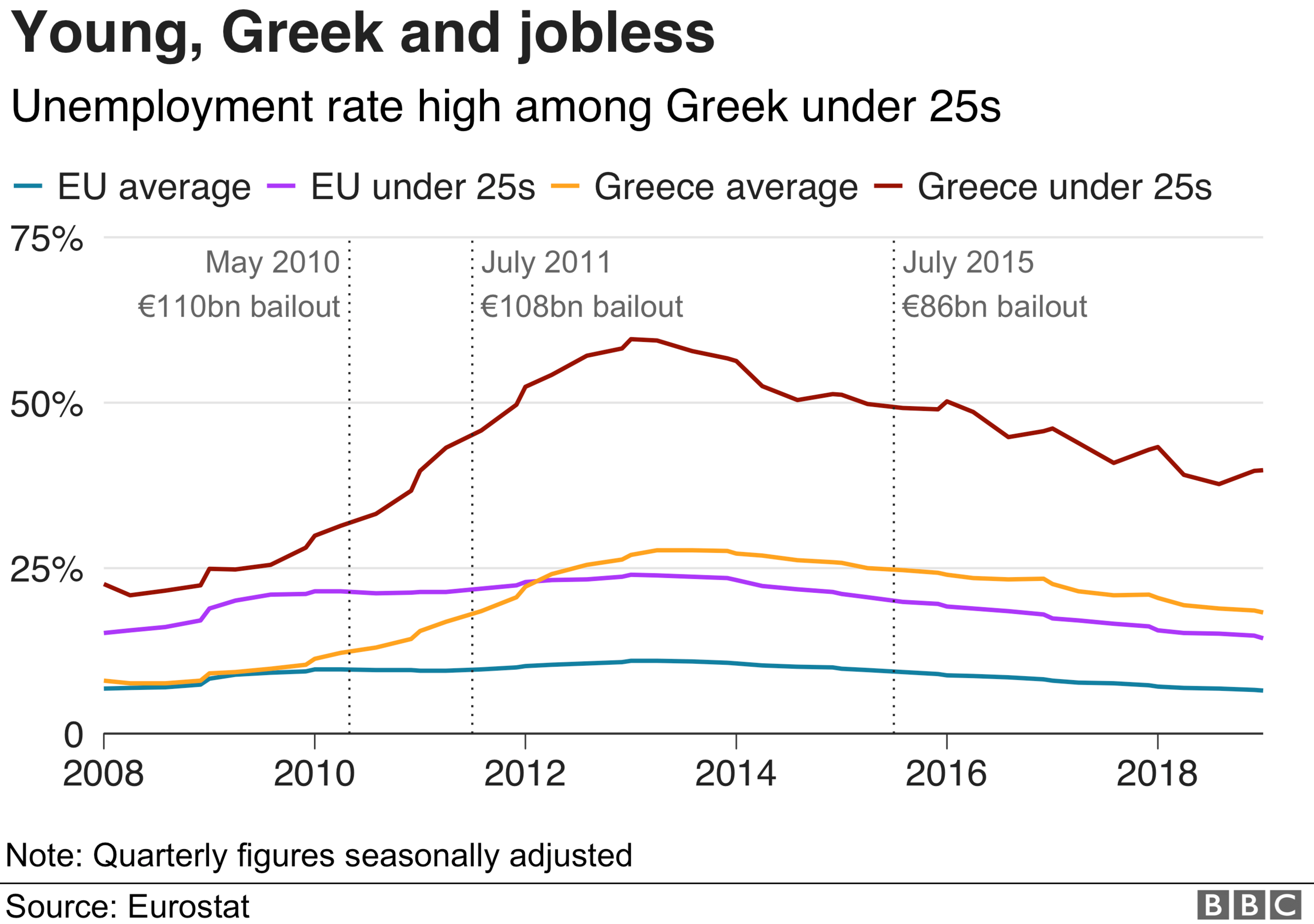

It was Greece's sixth general election since the global financial crisis in 2008, which hit the country hard and led to massive financial bailouts.

Here are some of the key issues that swung voters to the right.

1) Austerity and broken promises

In January 2015, voters backed Mr Tsipras's Syriza party, which campaigned to end the cuts imposed by Greece's creditors.

But the leftist party ended up implementing the tough bailout conditions from the EU and International Monetary Fund (IMF), in a chaotic year marked by bank closures and repeated votes.

After 2010, Greece received three packages worth €289bn (£259bn; $326bn), before exiting its last bailout in 2018.

Greek bailout: Five numbers that reshaped the country

The suffering went deep: between 2008 and 2016 the Greek economy shrank by a whopping 28%, and increasing unemployment threw many Greeks into poverty.

"It was a traumatic period; 275,000 businesses went under," Constantine Michalos, president of the Athens Chamber of Commerce, told the BBC ahead of Sunday's vote.

With a youth unemployment rate of almost 40%, between 350,000 and 400,000 graduates have emigrated since 2010.

The backlash for Syriza has been dramatic.

Despite the fact that Greece exited the bailout programme in August 2018 and growth has since returned, arguably as a result of Syriza's discipline, Mr Tsipras's popularity remained low.

"In the first quarter of 2019, growth has been restricted to 1.3%, which is weaker than expected, and this performance is a cause for concern for how we will end up this year," Mr Michalos said.

An EU report released last month highlighted Greece's high income inequality and urged investment in social services.

"Higher investment in education and training is crucial to improve Greece's productivity and long-term growth, external," the report said.

2) Greeks look to conservatives

Syriza rose to power on a strong anti-establishment platform, but disappointed many of its supporters, especially the young.

In May's European elections, the highest percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds (30.5%) backed Mr Mitsotakis's ND party, turfed out of power by Syriza in 2015.

Mr Mitsotakis, 51, has promised lower taxes, greater privatisation of public services and the creation of "better" jobs through growth and investment.

However, Greece remains under tight eurozone supervision, and any major tax or investment changes would have to be renegotiated with the country's creditors.

Mr Tsipras, 44, had also promised more investment and had in recent months boosted pensions.

2015: A street artist's graffiti guide to debt crisis

3) A name-calling controversy

Mr Tsipras's popularity was further dented by a deeply unpopular agreement that ended a three-decade name dispute between Greece and its northern neighbour.

In January, the Syriza-dominated parliament pushed through the landmark deal to rename its neighbour the Republic of North Macedonia, from the formal name of Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

Opinion polls indicated two-thirds of Greeks were unhappy with the name, because of its similarity to the northern Greek region of Macedonia.

Mr Tsipras then visited North Macedonia, where he posed for selfies alongside government buildings with Macedonian opposite number Zoran Zaev.

Selfie time: Macedonian PM Zoran Zaev (L) with Alexis Tsipras

As protesters displayed banners declaring "Macedonia is Greek", Mr Mitsotakis seized on the government's unpopularity, declaring the deal a betrayal.

Mr Mitsotakis has a personal stake in this story. His father, Konstantinos Mitsotakis, lost his job as prime minister in 1993 because of the name row.

4) Dealing with an influx of migrants

In 2016, the EU and Turkey signed an agreement aimed at stemming the number of migrants arriving in Greece, by sending back to Turkey those who do not apply for asylum, or whose claim has been rejected.

Since then, there has been a dramatic fall in refugees and migrants turning up in Greece.

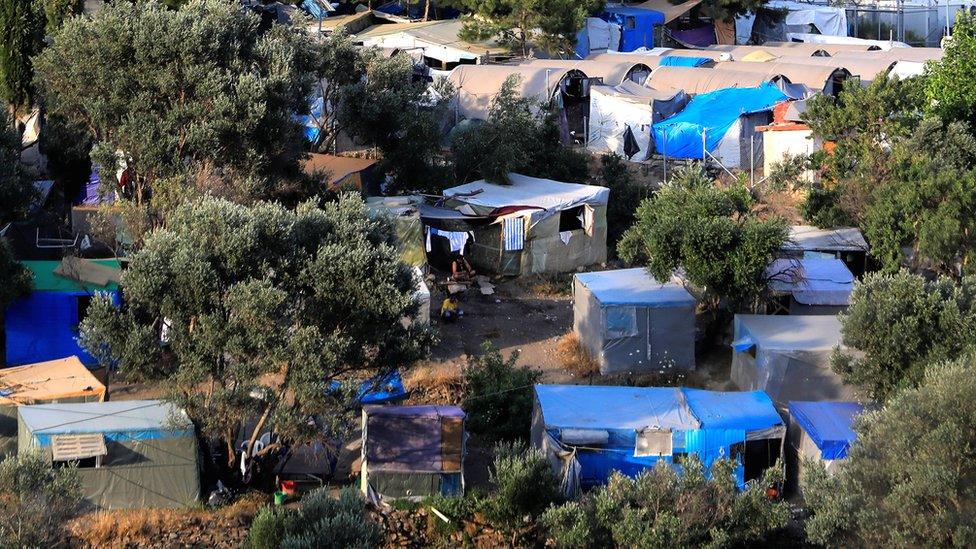

But they are still arriving, by sea and by land. In 2017, 36,000 came, with 50,000 last year.

Asylum seekers at Moria camp on Lesbos have complained of deadly violence

So far this year, 18,294 have come, according to the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR). Most of those crossing from Turkey are fleeing Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Feeling the pressure are the eastern Greek islands, such as Lesbos and Samos.

Mr Mitsotakis recently visited migrant camps on both islands, accusing Mr Tsipras of failing to stick to the Turkey agreement.

A migrant camp on the island of Samos, one of a number described as overcrowded

A makeshift camp set up on Samos to shelter about 650 migrants is housing thousands of people in poor conditions in temporary huts and tents.

5) Deadly fire that became political

Last summer, a deadly wildfire struck the seaside village of Mati on Greece's east coast - an area near Athens and popular with tourists.

The blaze trapped people in their homes and cars, while others fled into the sea to escape the flames. Many did not make it and 100 people died.

The Syriza government blamed unlicensed construction for hindering escape routes, but in the days following the tragedy, a catalogue of errors by local authorities emerged.

"The flames were chasing us into the water" - survivor

The then government's response prompted Mr Mitsotakis to call for those who had political responsibility to resign, as well as those who had the task of organising the response to the fire.

Syriza accused him of trying to exploit the tragedy.

In March this year, 20 people were charged over the tragedy, including politicians, police and fire officials. One minister did offer to resign but Mr Tsipras did not accept it.

A report by prosecutors found "there was an absolute lack of communication, chaos and a collapse of the system," and that officials had made "criminal mistakes and omissions during the handling of the wildfires".

- Published8 July 2019

- Published8 July 2019

- Published1 July 2019

- Published20 August 2018