Brazil election: Your guide in five charts

- Published

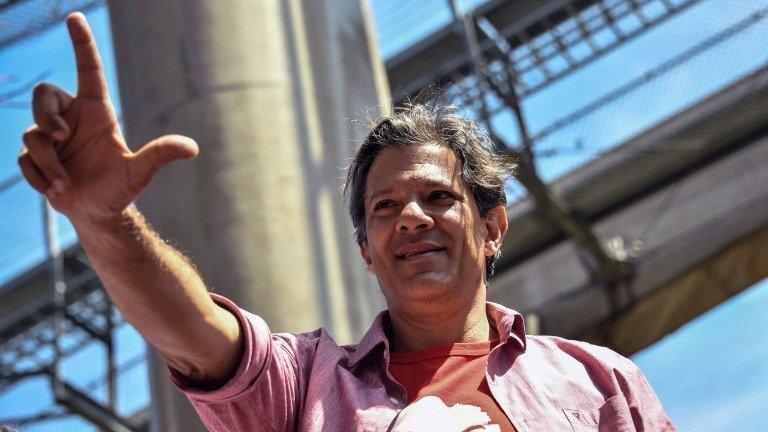

Brazil has elected a far-right president, with former army captain Jair Bolsonaro defeating left-wing candidate Fernando Haddad in Sunday's run-off vote.

Here, we take a look at some of the issues that were in voters' minds as they headed to the polls.

Threat to democracy?

Brazil is one of the world's most populous democracies, with almost 150 million voters. The question which worried some during the presidential campaign was: could a far-right president undermine Brazil's democratic institutions?

Brazil was under military rule from 1964 to 1985 and while some Brazilians fear a return to those times, others speak of nostalgia for what they describe as days of order. Mr Bolsonaro capitalised on the latter and has promised to fill his cabinet with generals.

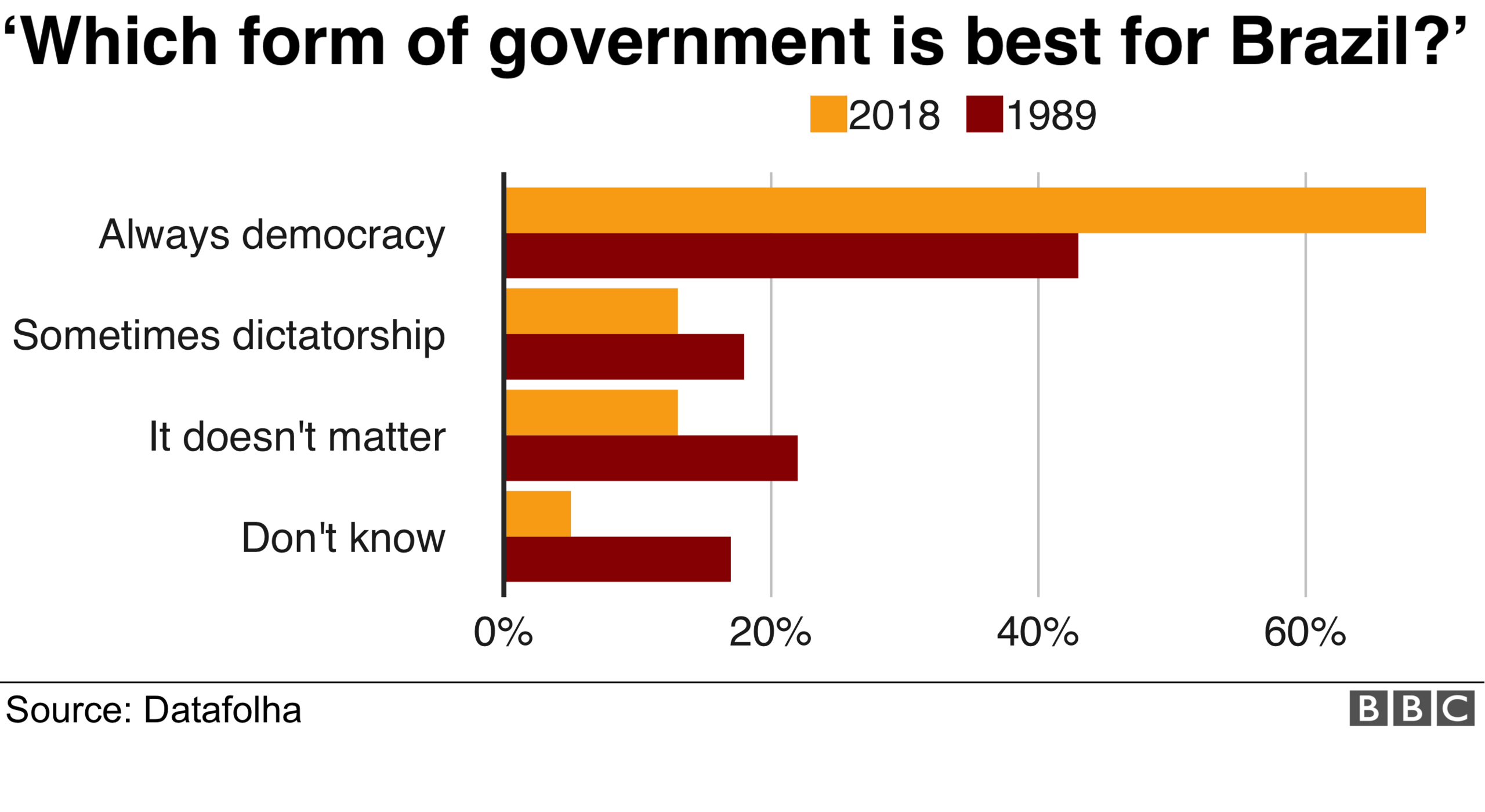

While his strategy clearly worked, a recent Datafolha poll also indicates that support for democracy has shot up in the past 30 years with 69% now saying they think democracy is the best way to govern, compared with 42% in 1989.

One thing most Brazilians seem to agree on is that they are fed up with politicians following the impeachment in 2016 of President Dilma Rousseff and a huge corruption investigation that has implicated countless politicians.

Read more:

Fear of getting caught in violence

Violence is a major issue in the country, with homicide on the rise. For many Brazilians, the biggest fear is stray bullets, accidentally being caught in a shoot-out while going about their daily business.

In the first half of 2017 alone, 632 people were injured by stray bullets in Rio state and at least 67 of them died, according to a report by Globo newspaper.

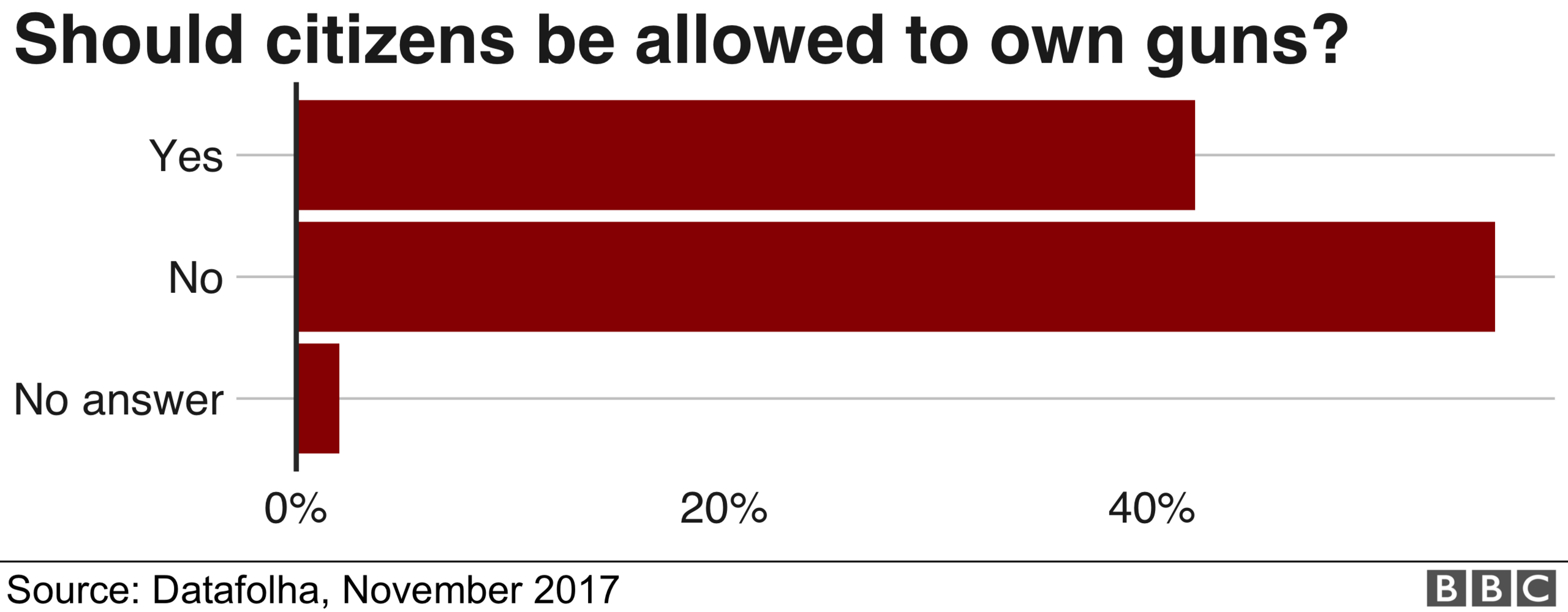

Some Brazilians feel that relaxing the law to make it easier to own and carry guns would bring increased protection, but according to a 2017 Datafolha poll, a majority oppose it, arguing this would only increase the chance of getting hit by a bullet.

The topic was a divisive one, with Mr Bolsonaro supporting liberalised gun laws and his defeated rival Fernando Haddad backing improved gun control.

Read more:

Lack of diversity

Brazilian politics is heavily dominated by white men and outgoing President Michel Temer was criticised when two years ago he created the first all-male cabinet since 1979.

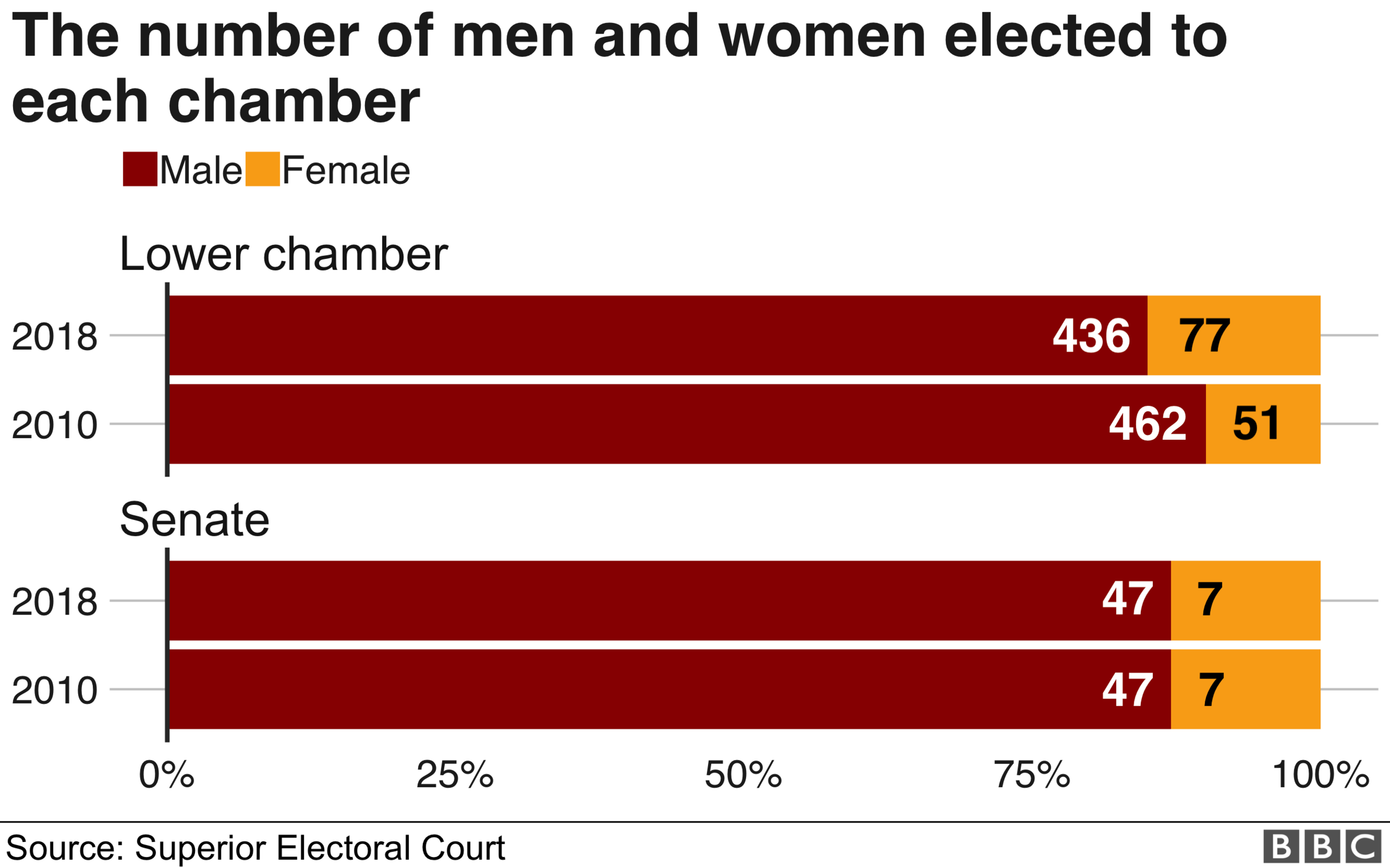

Women make up 52% of Brazilian voters, but only 31% of all candidates registered in the general election on 7 October - when 1,650 elected posts were up for grabs - were women, according to data from the electoral court.

While the number of women holding seats in the lower house has risen in the past eight years it has stayed the same in the Senate.

Black women and those from mixed backgrounds represent 27% of the country's population, according to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE), and yet they made up only 16% of candidates running for office at this election.

Mr Bolsonaro - who has made misogynistic, homophobic and racist comment during the campaign and before - alienated many female voters.

Hundreds of thousands of people have taken part in street protests against his candidacy but a recent poll suggested more female voters - 43% - were planning to cast a vote for him than the 39% planning to vote for Fernando Haddad.

Read more:

Health and welfare

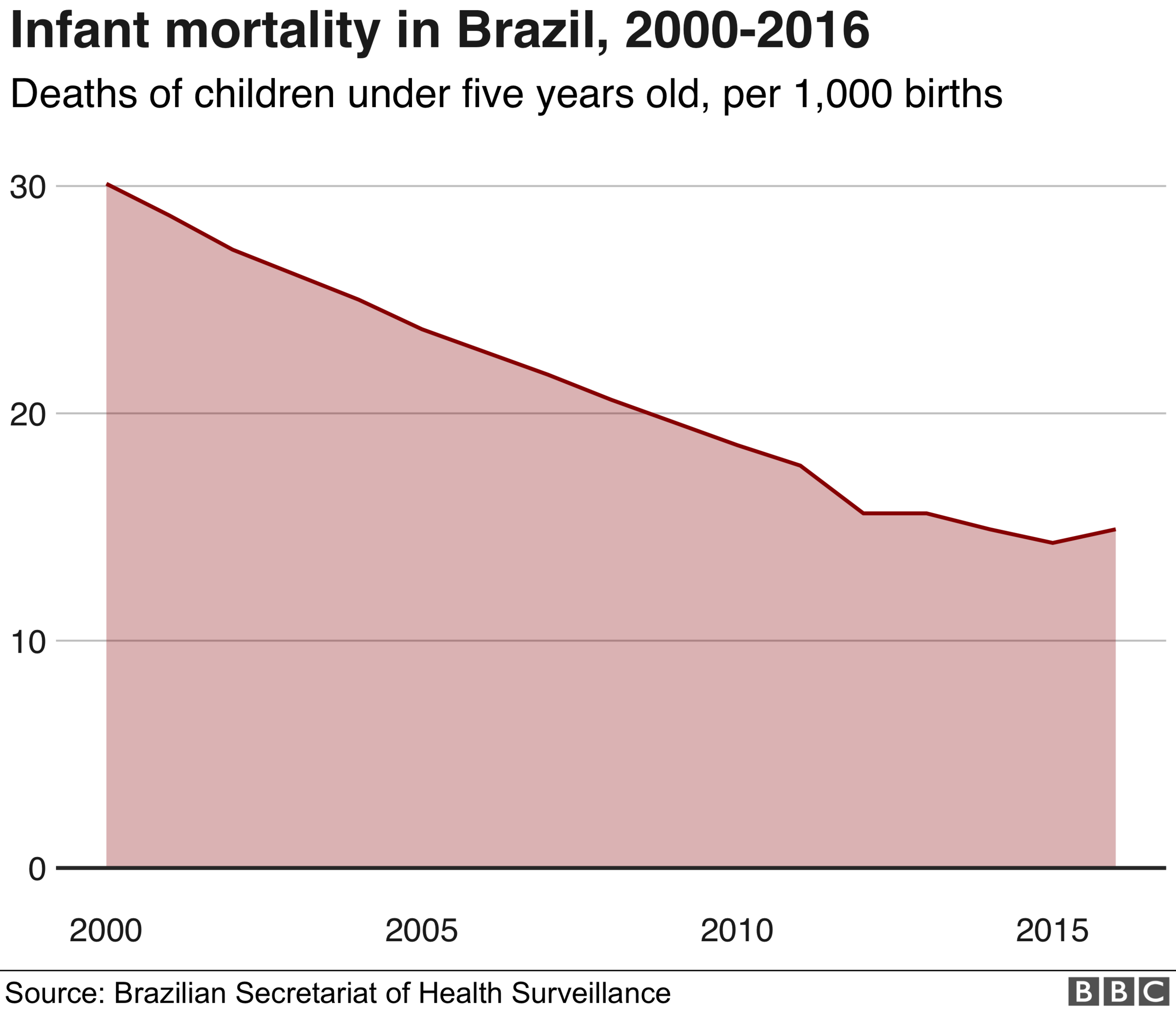

Brazil has been praised for its work to reduce infant mortality in recent years, but the latest figures have shown an increase.

Health ministry numbers for 2016 showed the number of infant deaths at 14 in every 1,000 live births, a 5% increase on the previous year. The increase is the first since the current tracking system was implemented in 1990.

The ministry cited the economic crisis and the outbreak of the Zika virus - which was linked to an increase in birth defects - as explanatory factors.

Mr Haddad and his party campaigned on a promise to reverse austerity measures and to enforce "fiscal responsibility with social responsibility".

In an effort to win votes in Brazil's poor north-east - where Mr Haddad won 51% of the first-round votes compared with 26% who voted for Mr Bolsonaro - the latter promised to update the welfare programmes to encourage those receiving payments to search for jobs by not cutting off their benefits when they found work.

Read more:

Displacement and deforestation

Four percent of Brazilians had to leave their homes because of natural disasters or development projects between 2000 and 2017, according to research organisation Igarapé.

The biggest factor driving people from their homes was flash flooding, which has been blamed on deforestation.

While Brazil reduced the rate of deforestation by 16% in 2017, some worry it could be on the rise this year as a result of environmental agencies having had their budgets slashed as part of austerity measures.

However, these worries do not appear to be swaying voters. In the first round of the presidential election, Marina Silva, a former environment minister who has addressed the issue, only got 1%. Mr Bolsonaro has the backing of agribusiness and has said he will to pull Brazil out of the Paris climate deal and abolish the main government agency tackling deforestation.

Read more:

- Published25 October 2018

- Published31 December 2018

- Published21 September 2018

- Published6 October 2018

- Published9 March 2017