Puerto Rico: The Greece of the Caribbean?

- Published

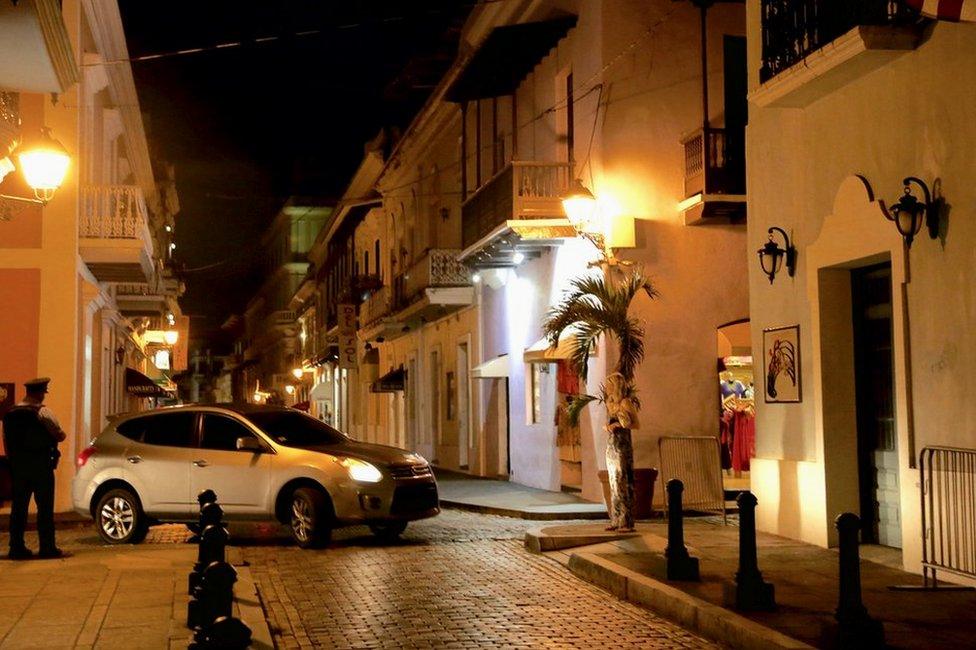

Take a walk around the old town in San Juan, and you would be hard pressed to find evidence of the abominable situation Puerto Rico is in with its public finances.

The bars appear to be thriving, the restaurants full and there seems no shortage of the tourists that flock to this Caribbean sun spot.

But behind the facades, things are bad.

Porfiro is 22. Tall, lanky, and slightly balding, he is the new generation of businessmen. He is following in the footsteps of his grandfather, running the harbour brewery. The business specialises in craft beers, all brewed on the premises.

"It's tough," he says. "Sometimes we get good business, sometimes we don't."

He says the customers are unpredictable. Some Fridays the bar can be full, others it is completely empty.

And that can only get worse, he says, when the sales tax is raised by 4.5% on 1 July - one of the measures the government here has introduced to try to get a grip on its debts.

The scale of the problem is shocking.

Puerto Rico has $72bn (£46bn) of public debt. That makes it by far the most indebted territory or state per capita in the United States.

Not only that, but unemployment here - at almost 14% - is more than double the national average.

Add to all that a decade of little or no growth and you have an economy that has deep structural problems, teetering on the edge of oblivion.

The government's response has been to spook the bond markets by suggesting that it could default on its debt payments.

Governor Padilla told the New York Times that the island's debt "is not payable".

When the governor, Alejandro Garcia Padilla, dropped that bombshell at the beginning of the week, the island got a new nickname: the Greece of the Caribbean.

That threat seems to have brought the New York money men to the table to start negotiating how Puerto Rico can begin to dig itself out of the hole it is in.

A couple of big payments have been made - $600m worth of general debt servicing on Wednesday, and the island's power company has found a few hundred million to keep its creditors at bay.

But none of this addresses the long-term issue.

Pinky's Restaurant has been waiting to open a new outlet for 6 months

Alex, owner of Pinky's Restaurant in the Carolina district, rails against the bureaucracy that is stifling growth.

He has been trying to expand his outlets, wanting to set up a food cart in another part of town. Because the developer failed to pay for a permit to tarmac the area, the government, he says, is preventing his and other businesses from moving in and creating 30 jobs. He has been ready to open up for six months.

Others choose simply to leave.

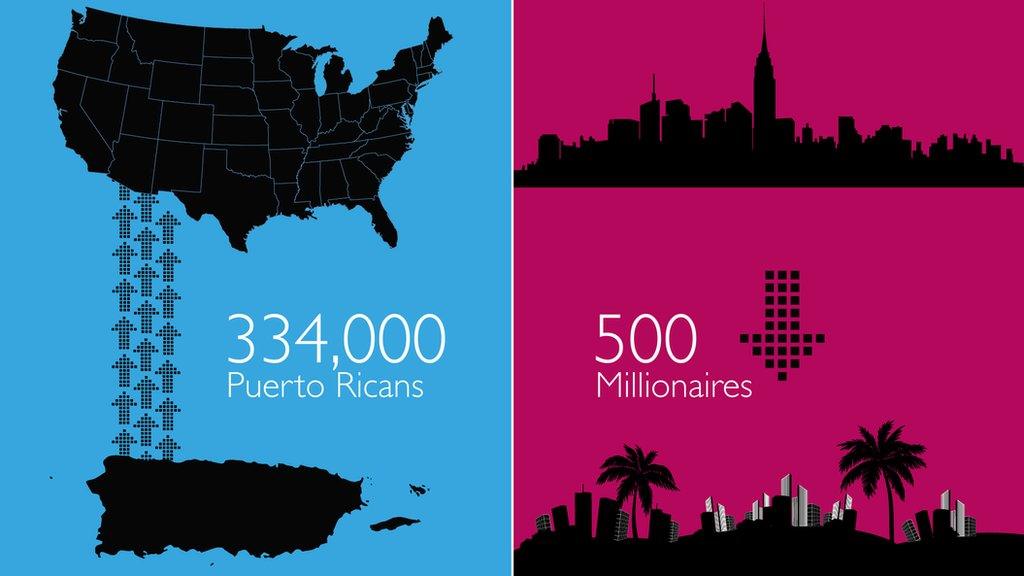

The island has been losing 1% (around 30,000 people) a year to Florida and other parts of the US. And it is mainly the economically active young who are leaving.

"I think there's no future for me here," says Jose, a nursing student. "In like one or two years, I think I will move out to the States. Because here for me in Puerto Rico there's no future."

Luis, who's training to be a pharmacist, agrees. "My personal opinion would be that professionals in Puerto Rico have almost no future."

Puerto Rico's students sound off

Melba Acosta, head of the development bank which controls public finances, tells me that the administration has cut spending and raised taxes and will do so again.

But with a damning report from several former International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists on her desk, she accepts that a restructuring of the debt will be necessary.

"Come to the table and talk," is her message to the hedge funds that have allowed Puerto Rico to finance years of deficit with debt.

"We understand that the first option for the creditors is to have their money now," Acosta says. "But we don't have access to the market now, so we can't keep borrowing to pay our debts."

Development bank president Melba Acosta said spending cuts are likely

The government is rejecting some recommendations from the IMF economists, notably the idea of allowing employers to pay less than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. There is also resistance to cutting the bloated public sector, which accounts for almost 20% of the workforce.

Puerto Rico has also been lobbying to be allowed to file for bankruptcy, much as Detroit did in 2013. That would give it a breathing space and certain rights to restructure the debt. But that option is not open to the island legally, and thus the creditors have the government here over a barrel.

The federal government has hinted that it might be a good idea for Congress to consider changing the law to give Puerto Rico bankruptcy rights, but has itself ruled out any kind of bailout.

And the island's status as a territory, with no voting members in Congress, gives it little political clout.

Pedro Pierluisi is the island's sole representative in the nation's capital, and he has no voting rights at all. He says this lack of clout means Puerto Rico also does not get its fair share of federal funding for other programmes.

"It's pretty embarrassing to be a citizen of a nation where you cannot vote for the president…The same goes for Congress," he says. "And lastly to be treated unfairly, not to say discriminatorily, in key federal programmes like Medicare and Medicaid."

For the time being Puerto Rico has avoided defaulting on its debts, but only just. The problems here run deep and they will take years to sort out.

By the time that happens, young Porfiro may have already left - heading for a medical degree in Florida - leaving the lovers of craft beer to fend for themselves.

- Published30 June 2015

- Published5 May 2015

- Published11 September 2023