Puerto Rico debt crisis: How did we get here?

- Published

Puerto Rico continues to struggle under a massive debt crisis and a flagging economy. How did the situation get so bad? And what can be done?

The situation has been dire for some time, with the semi-autonomous US territory suffering from an economic recession for nearly a decade.

But alarm bells truly began ringing during the summer of 2015 when Puerto Rico's governor, Alejandro Padilla, said that the island would be unable to pay its bills.

An island, indebted

$72bn

total debt

-

$20,724.30 approximate debt per person

-

2 number of defaults so far

-

9 approximate number of years of recession

Since then pundits have begun calling it the "Greece of the Caribbean," and Mr Padilla has warned of a humanitarian crisis that could unfold if the crisis worsens.

How did the situation get so bad?

Shortly after World War II, the US began implementing a series of development programmes, which transformed the economy.

Among the initiatives were tax breaks, the most famous known as Section 936, which was implemented in 1976, and exempted US companies from having to pay federal tax.

It had been one of the great postwar economic-development success stories, turning itself from a poor, largely rural society into a manufacturing powerhouse.

Fast forward 20 years, and the US government was looking to cut costs and balance its budget, and Section 936 was labelled "an expensive giveaway", external.

Puerto Rico's leaders warned of dire consequences if it were taken away, but the tax incentive was phased out over a decade beginning in 1996, and the economy entered recession in 2006.

As the economy has suffered, the island's government has had to borrow large amounts of money to maintain the quality of life that Boricuas - as the island's residents affectionately call themselves - had grown accustomed to.

Who is asking for what?

Governor Padilla is asking for the US Congress - to which Puerto Rico sends a non-voting observer - to grant the island's public utility companies and other institutions the right to declare bankruptcy and restructure debts, which is the same right their mainland counterparts currently enjoy.

He has repeatedly made the point that the island is not seeking a bailout, and the White House has ruled one out as an option, saying debt restructuring is the way forward.

What can the US Congress do? And what are they doing?

Democrats say that allowing the island to restructure debts, as Mr Padilla and the White House propose, would not cost taxpayers and is the right solution.

Republicans in Congress say that they want to see so-far undisclosed economic data from the island and to address the problem's root causes.

House Speaker Paul Ryan, a Republican, has said his chamber will come up with "a responsible solution" by the end of March, but his counterpart in the Senate has made no such promise.

Governor Padilla has warned of a humanitarian crisis if a solution is not found

How do people on the island feel?

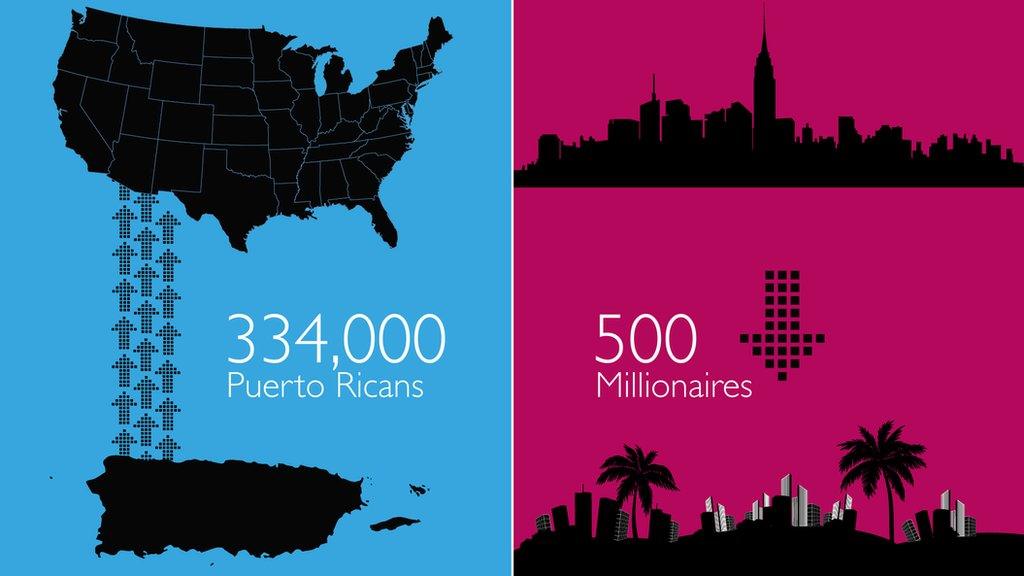

Around 10% of the island's population has left in as many years. Today, as many as 3,000 Boricuas are fleeing the island each week, according to the US Treasury Secretary.

The governor has warned that if a solution is not found, he will have to start sacking police officers, fire fighters, and other employees.

He said that ultimately a humanitarian crisis could emerge.

Meanwhile, the issue has become political, with statehood supporters saying the crisis demonstrates why the island should become the 51st US state and Independence activists say it demonstrates US indifference towards the island's welfare

- Published11 September 2023

- Published29 July 2019

- Published6 July 2015

- Published5 May 2015

- Published30 June 2015

- Published20 January 2016

- Published1 December 2015

- Published5 January 2016

- Published4 August 2015