1968 Democratic National Convention: A 'week of hate'

- Published

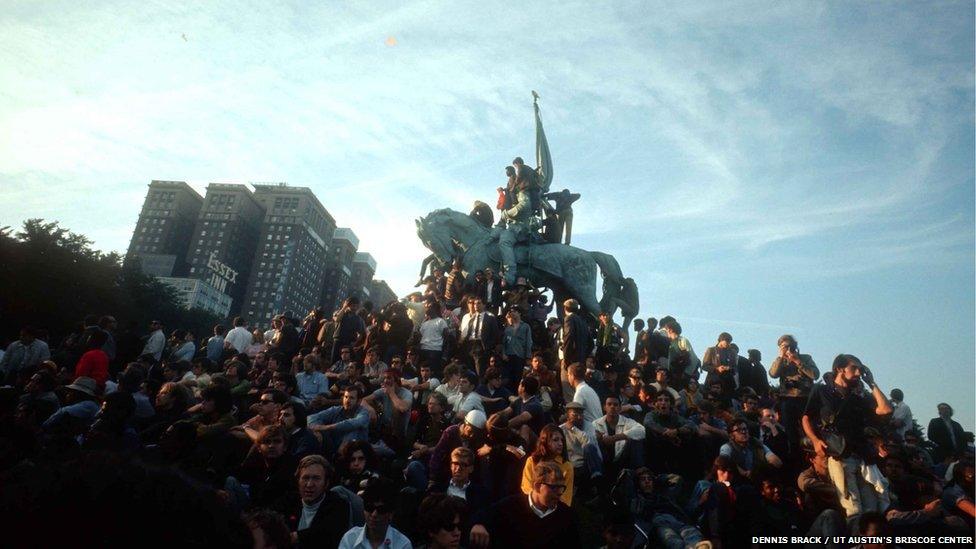

Demonstration in Chicago's Grant Park

More than 50 years on, the Democratic Party's national convention of 1968 continues to haunt the party and cast a shadow over US politics, writes James Jeffrey.

The signs before the Democratic National Convention convened in Chicago from August 26 - 29 in 1968 were never good.

Anti-war protesters began arriving in the city the week before, vowing to change the party's policy toward the increasingly hated Vietnam War.

They included New Left radicals, long-haired hippies and so-called Yippies, members of the Youth International Party, a radical youth-oriented and countercultural offshoot of the 1960s' free speech and anti-war movements fomenting against the US government.

Some were bent on disrupting the convention by whatever means necessary, while others focused on more leftfield tactics such as holding a counter convention offering the likes of a nude grope-in for peace and prosperity, and workshops on joint rolling, guerrilla theatre and draft dodging.

Rumours were floated by some of the more imaginative protesters that they were going to inject LSD into the city's drinking water, and send out "stud teams" to seduce the wives and daughters of the delegates - all designed to unnerve the Democrat delegates and keep the Chicago police and investigative agencies guessing.

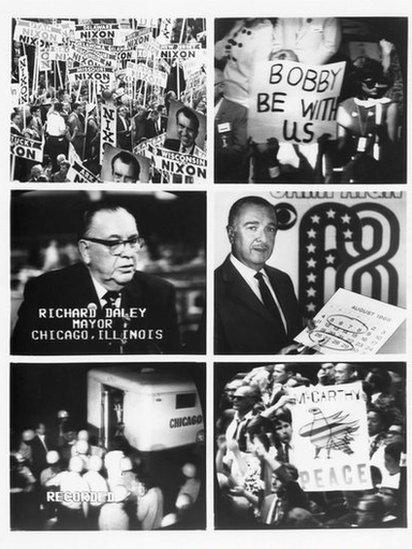

The city's tough-talking mayor Richard Daley wasn't taking any chances.

The force he mobilised against demonstrators included all the city's 12,000 police, supported by 6,000 armed National Guardsman and 1,000 intelligence agents from the FBI, CIA, Army and Navy. Another 6,000 US Army troops were put on standby.

"Not all protesters are angry, they have a point to make, but these protesters regarded the police as pigs, who in turn regarded them as draft-dodging hippies," says photojournalist Dennis Brack who covered the convention.

The International Amphitheatre hosting the convention was encircled by barbed wire and a long, high chain-link fence, while an 11pm curfew was imposed across the city.

The worst was expected by the city's authorities, and before the convention was over it had happened - a chaotic, bloody shambles from which the Democrat Party never fully recovered, changing and influencing the American political landscape up to today.

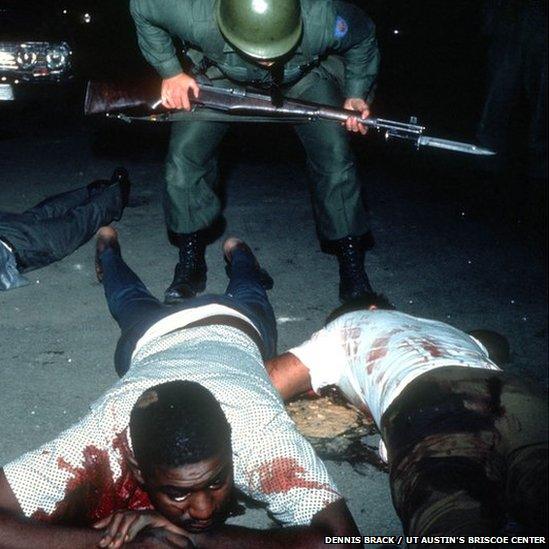

Wounded civilians during Detroit riots of 1967, a precursor to the tumult in Chicago

"It was the most intense week of hate I've ever experienced," Mr Brack said in an oral history interview given to the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History in Austin, Texas, which houses Brack's archives.

"Combat heat is different. This was plain old one group hating another. I always stayed closer to the older cops. They were safer. But the younger cops could really hurt you."

As delegates checked into the Conrad Hilton Hotel near the convention centre, organisers of the protests were placed under electronic and direct personal surveillance, roadblocks barred avenues of entry, and jeeps with barbed wire on their bumpers took armed troops to expected trouble spots.

"It was a city under siege, like the sort of thing you would find in a third-world city," says Stephen Shames, who attended the convention both as a journalist for the underground press and as a protester.

America was on the edge - the decade appeared ensnared in unending violence both abroad and at home.

Detroit had been torn apart during the long, hot summer of 1967 by violent and bloody confrontations between blacks and police.

Riots had broken out in the capital Washington earlier in 1968 following the April assassination of Dr Martin Luther King, which was followed in June by the assassination of senator Robert Kennedy.

"We'd been covering confrontations and riots for two to three years," Mr Brack says. "All the journalists had their own riot gear, it was expected to happen back then. It was just another day at the office."

By Sunday 25 August, the day before the convention started, the city's Lincoln Park has been taken over by anti-war demonstrators waving banners and shouting obscenities about President Lyndon Johnson and chanting "Hey, hey, LBJ! How many kids have you killed today!"

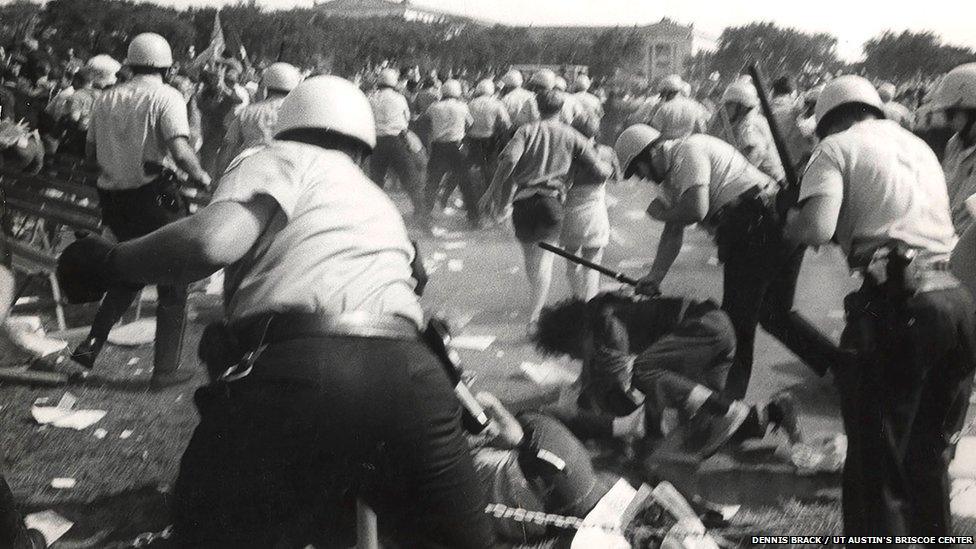

Policemen advancing against protesters during 1968 convention

That night about a thousand demonstrators defied the curfew, resulting in an estimated 500 police wading into the park waving truncheons.

"Their predominantly young prey fled or turned and hurled rocks, bottles and profanities at the enforcers, as reported and cameramen captured the scene," Jules Witcover, a journalist covering the convention, later wrote in his book The Year the Dream Died: Revisiting 1968 in America.

More voices on US history:

The animosity found its way into the International Amphitheatre when the convention started the next day.

Heated arguments and even scuffles broke out as the convention descended into a convoluted mess over what policy to take on the Vietnam War and who should be the Democratic nomination to run for president. Everything ran over schedule.

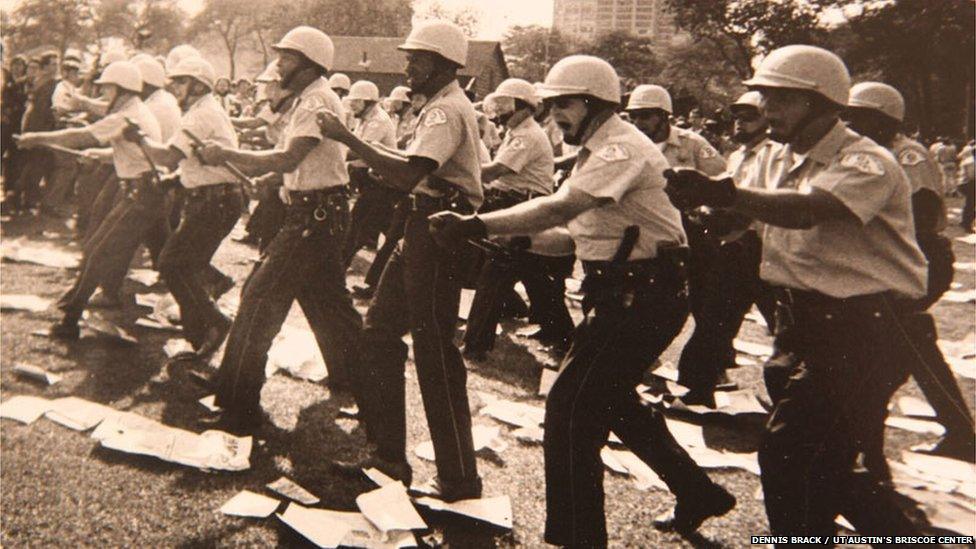

A group of policemen in riot gear confronting a crowd at the convention

Come Tuesday night, even more protesters in Lincoln Park refused to observe the 11 o'clock curfew.

The police poured tear gas into the park, eventually driving out about 3,000 mostly young protesters, arresting 140 of them.

"Police burst out of the woods in selective pursuit of new photographers," Nicholas von Hoffman wrote in the Washington Post.

"Pictures are unanswerable evidence in court. They'd taken off their badges, their name plates, even the unit patches on their shoulders to become a mob of identical, unidentifiable club-swingers."

The police knew they could get away with it.

"The city of Chicago ran on officially sanctioned violence," says University of Texas history professor James Galbraith, who attended the convention as a 16-year-old with his delegate and floor leader father.

"The protesters were an affront to the mayor's management of the convention, Daly was embarrassed and had no qualms about teaching them a lesson."

Clashes continued at other parks around the city, while inside the convention hall the atmosphere didn't improve.

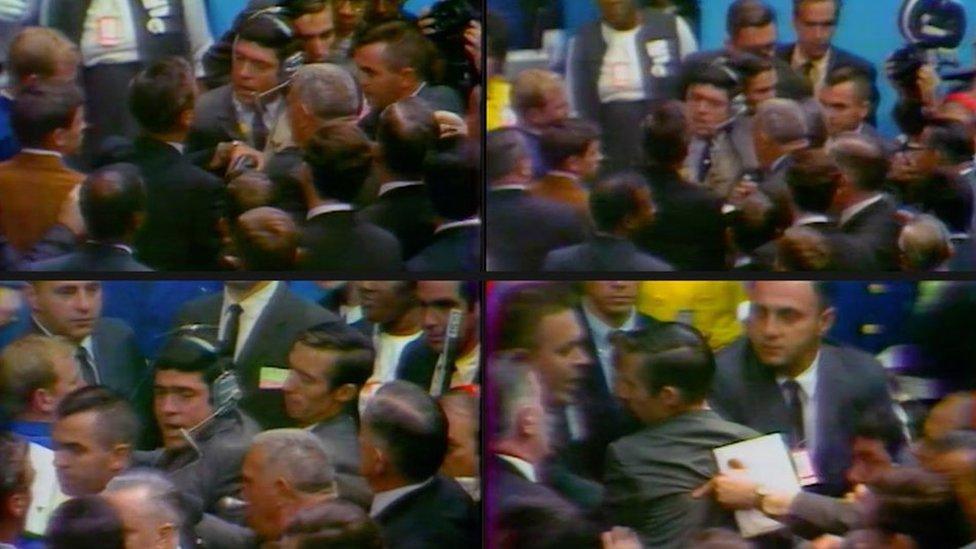

Images of journalist Dan Rather being harassed

At one point, Dan Rather, a well-known journalist covering the convention for CBS television, was assaulted on the convention floor by security personnel as he attempted to interview a delegate.

"Take your hands off me unless you plan to arrest me," Mr Rather shouted.

"I think we've got a bunch of thugs here, Dan," Walter Cronkite, a CBS colleague with Rather, remarked on air.

Eventually the crowds outside decided to try and march on the convention hall and Conrad Hilton hotel.

The marches converged on Michigan Avenue and Balbo Drive where they met a police block. As protesters began chanting "The whole world is watching!" the police fired gas into the crowd, then charged and started to club whoever was closest to hand.

"Journalist felt their press cards would mean they'd be left alone - they were sorely disappointed," Mr Shames says. "The rules changed in Chicago."

What was later declared a "police riot" was beamed by television cameras into the convention hall itself and millions of American homes.

"In approximately half an hour, the complete breakdown of true law and order, and of the soul of the Democratic Party was shatteringly exposed on Michigan Avenue," Mr Witcover says.

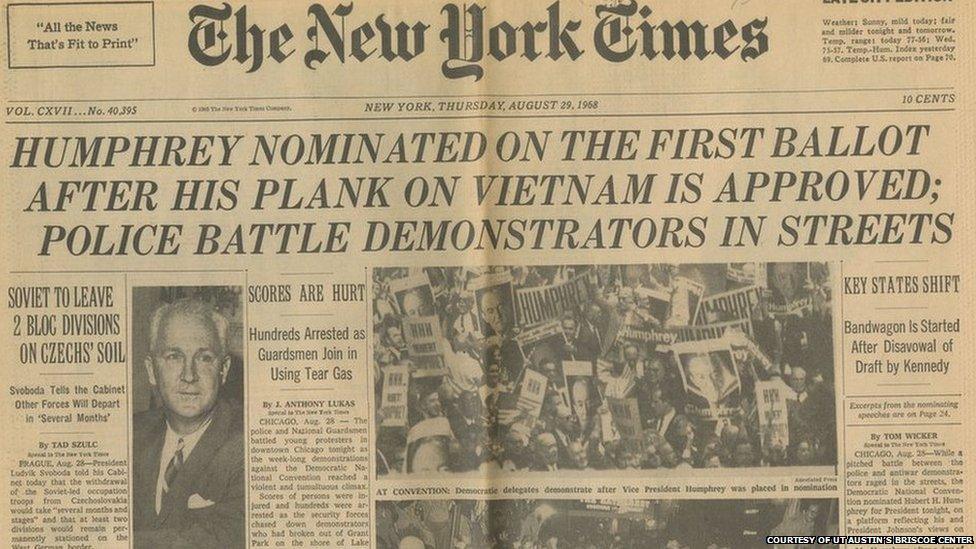

Newspaper article describing the protests, published in The New York Times, 1968

By the end of the convention, the delegates finally managed to vote on Hubert Humphrey, the serving vice-president, receiving the Democratic nomination, although this incensed many protesters who saw it as an endorsement of more of the same, especially in relation to the war in Vietnam continuing.

The damage had been done, and the contrast with the orderly Republican National Convention that had occurred earlier at the beginning of August couldn't have been starker.

"The Democrats gave themselves a deep wound in 1968," Mr Galbraith says. "Scenes of highly telegenic violence conveyed the deep split and breakup of the Democratic party over the Vietnam War."

It was a gift to Republican politicians, including their party's presidential nomination, Richard Nixon, who offered his party as the only alternative that could resolve the Vietnam War dilemma peacefully and restore law and order at home.

"The shaken nation was set on a course of disappointment and division and self-doubt that bred distrust of its leaders and institutions, apathy and ultimately hostility toward both," Mr Witcover recalls in an online exhibition, external on the events of 1968 by the Dolph Briscoe Center.

"[1968 became the] pivotal year [when] something vital died - the post-World War II dream of an America that at last would face up to its most basic problems at home and abroad with wisdom, honesty and compassion."

Nixon won the subsequent presidential election that year, and then went on to win the 1972 election by a landslide - garnering 520 electoral votes to the 17 of Democrat nominee George McGovern.

Although the Democrats got back into the White House in 1977 with Jimmy Carter defeating Gerald Ford, it didn't last long.

By 1981 the Republicans were back in with the election of Ronald Reagan, who proceeded to reverse much of the Great Society, a set of domestic programmes to eliminate poverty and injustice, envisaged and started by Lyndon Johnson and the Democratic Party.

"The Democrat party lost its working-class base," Mr Galbraith says.

"Today it appeals to two tails of the economy: well-off urban professionals and minorities, making it hard for the party to have a coherent message, which is what the Republicans have. The Democrat split deepened and led to Donald Trump today."

Another lesson from Chicago that persists today, Mr Galbraith notes, was about how authority in America reacts to dissenters.

The sanctioning of official violence against minorities and counterculture has become an "American way of life," he says, which may partly explain why the level of protests seen in 1968 hasn't occurred again.

"Now there are a range of surveillance powers to increase the intimidation of organised street protestors, while the explicit militarisation and increased lethality of the police has been an ongoing issue," Mr Galbraith says.

"In 1968 they went in with tear gas and billy clubs - today if there was a similar situation it's hard to imagine what might happen."

- Published26 August 2015

- Published3 November 2012

- Published9 July 2013

- Published30 April 2019