Six-day racing: Madisons, mayhem and the Ministry of Sound

- Published

Six-day racing requires strength and stamina, and that is just for the fans; the riders need good legs and even better luck

It started with a bet, burned bright in America's Jazz Age, became a European winter staple and is now back, almost where it started, after a 35-year absence.

Six-day racing has been around fashion's revolving door a few times but - if the organisers of a new event, external starting in London on Sunday have timed it right - this Ben-Hur-with-bikes marathon, for a darts and dance music crowd, could become this season's sensation.

'Six-day racing is the Tour indoors'

But it is also probably fair to say that most British sports fans have never heard of six-day racing, let alone seen it, and even cycling's most dedicated followers could be forgiven for being a little vague on the details.

After all, this is a variety of racing not seen in these parts since 1980, and the intervening years have often seen it dismissed as, at best, a bit of fun while we wait for the weather to improve and, at worst, fixed racing on fixed-wheel bikes, featuring guys on speed, roared on by drunks.

So what is it exactly, who is riding, how do you win and when does the disco start?

From boom to bust in America

For a period of history that is best known for empire, industry and straitlaced propriety, Victorian Britain also enjoyed betting on ridiculous physical challenges: swimming races against dogs, wrestling bears, playing cricket for five days and so on.

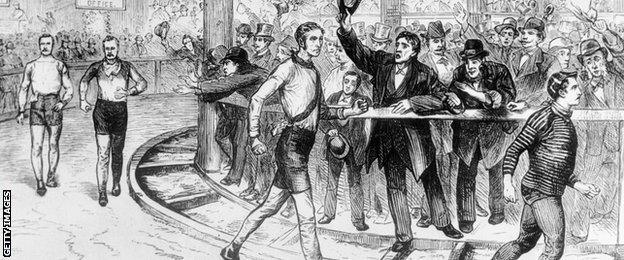

Victorian Britain loved sporting challenges, as this contemporary sketch of a six-day walking event suggests - bikes added a dollop of danger

It was in that "go on, I dare you" spirit that a Mr Davis bet professional cyclist David Stanton £100 that he could not ride 1,000 miles in a week, excluding Sunday's day of rest, of course.

Stanton set off on a penny-farthing, on a temporary track at Islington's Agricultural Hall, early on Monday, 25 February, 1878. Five uncomfortable days later, he had his £100.

The venue, which is now the Business Design Centre,, external had already staged a six-day walking race - an event that drew 20,000 punters a day - so it was not too much of a leap to put on a six-day, no-napping bike race in November 1878, a spectacle that was repeated up and down the land at least 30 times over the next three years.

But it was in the US that it really took off, particularly at New York's Madison Square Garden,, external an arena best known for prize fights, circuses and other popular dramas - the sleep-deprived racers fitted right in.

Amid concerns that riders were popping amphetamines to fight the fatigue, local authorities brought in a 12-hour limit, a move the race organisers countered by making them two-man events, so one rider could race while the other slept, usually in basement dorms.

As bikes and tracks improved in the early decades of the 20th century, the speeds and distances travelled went up, as did the crowds. This was six-day racing's gilded age as Hollywood celebrities mixed with gangsters at track centre and the biggest jazz bands of the day provided the soundtrack.

And then, almost as quickly as they got hitched, America and six-day racing split up.

Whether it was baseball, the Great Depression, the rise of the automobile or too many foreign riders that did it, the game was up by the 1950s.

Not fixed, just fast

But the New World's loss was the Old World's gain as the American formula of bikes, booze and bravery had become a fixture in European cycling's heartlands.

Robert Dineen's, external recently published history of British cycling, "Kings of the Road", describes this chapter in six-day racing's story as "highly lucrative, unspeakably tough, possibly shady and certainly confusing" and its stars were "the most technically accomplished cyclists in the world".

Even after the 24-hour sessions were phased out, six-day racing was as much a test of a rider's ability to rest in cramped spaces as his legs, and while the money was good, the lodgings were lousy

From Antwerp to Zurich, an elite group of track specialists would team up with - or take on - star turns from the world of road cycling in an exhausting schedule of late nights and packed houses. These were hard men capable of riding 35mph for hours at a time, six nights a week.

Rob Hayles, a double gold medallist at the 2005 World Track Championships, rode 21 sixes between 1996 and 2005 and ticked off every major stop on the circuit. He remembers the "shadiness" but says it is more complicated than many would have it.

"It wasn't all fixed but the big teams would look after themselves - it would nearly always come down to a shoot-out between them on the final evening," said the Briton, who also won three Olympic track medals.

"But you needed to be very strong, very aware of what was going on and a bit lucky to win. Even then it was very, very hard to win, although it was quite easy to stop somebody else winning.

"And that's my main memory of them: the best teams would just beat you up."

British cycling's Middle-six man

Dineen's description of the scene comes in a chapter on Tony Doyle,, external who rode his first six-day race, the Skol 6,, external at Wembley Arena in 1980.

That would be the last such event in the UK for 35 years but it planted a seed as Doyle would spend the next decade becoming Britain's most successful exponent of the event.

He earned that initial invite by winning the world pursuit title earlier that year, so he was no mug, but it would take him three years to earn his spurs in this company and start winning races.

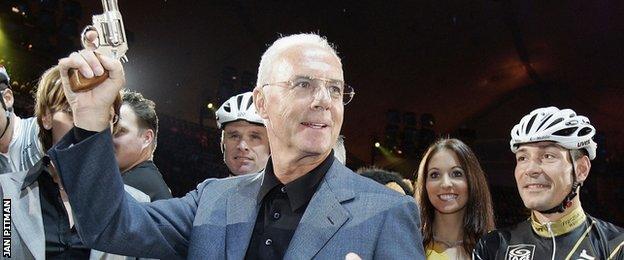

There is always an element of the Wild West at the big German sixes, as football legend Franz Beckenbauer demonstrates in Munich

Doyle was regularly paired with Australian track great Danny Clark, although he was sometimes given the job of shepherding big names from the road through what was, to many of them, a terrifying ordeal.

Recalling those days now, when he rode up to 16 six-day races a year, half of them in Germany, Doyle reels off Tour de France champions Laurent Fignon, Greg LeMond and Stephen Roche as former partners.

But he also talks fondly about performing to nearly 150,000 fans in Bremen, the 100,000 who would regularly come to Munich's Six, the nightclub that would open there when the racing finished at two in the morning, Sunday's kids-for-free sessions and Monday's "women's nights" when the clientele would make most of today's promoters blush.

"The racing was serious, though, and dangerous if you got it wrong," said Doyle, who should know, he was given the last rites whilst in a coma in Munich after a terrible crash in 1989.

He would come back 12 months later and win it again with Clark.

Back from the dead

The Londoner's riding career came to an end in 1994 when he broke his back in a crash at a six-day race in Zurich, but he stayed in cycling, helping to get the Tour of Britain , externalrestarted in 1994 and becoming president of the British Cycling Federation in 1996. He would later work for Nike and chair the London borough of Southwark's Olympic legacy board.

His passion for six-day racing never diminished, though, which is crucial to this story as the circuit needed cheerleaders as determined as Doyle.

What had once been a crowded calendar was getting sparse as the millennium turned, with venues realising they could make easier money from pop concerts, while the best riders preferred road cycling's steady salaries. Six-day racing looked like it might have had its day.

London's Olympic velodrome has earned a reputation for being one of the world's fastest tracks but it needs a regular stream of world-class events to showcase that

But several factors combined to get fashion's revolving door moving again.

First, British track cyclists started to win serious amounts of medals and these newly-minted champions would need more regular exposure.

Second, London won the right to stage the 2012 Olympics and Paralympics: this would mean building a velodrome and then filling it regularly.

And third, we all went a bit bonkers for biking, be it as a way to lose weight, get to work, see the countryside or display our wealth.

Having come close to bringing a six to London's ExCel in 2008 - only for the credit crunch to intervene - Doyle kept plugging away at his contacts in London's investment banks, the cycling world and those responsible for ensuring London's Olympic legacy.

Seven years later, six-day racing is back in the capital, less than five miles from where it started, 137 years ago.

Six formats, lots of laps

Six Day London - which starts on Sunday, 18 October, and runs until Friday, 23 October - is not quite a classic six but it is close.

Because of the overlap with the European Track Championships in Switzerland, the opening day at the Lee Valley VeloPark is a standalone event called the 1878 Cup, which will run as an omnium-style,, external points-based competition. It is also a matinee performance, aimed at families.

Madison men Rob Hayles and Sir Bradley Wiggins execute a textbook hand-sling, cycling's most exciting helping hand

Come Monday, with the riders all present, the real deal begins, with 18 men's pairings spending the next five nights (the sessions run from 1730 to 2230) doing battle; and nine women's pairings taking part in a three-day omnium from Wednesday.

For the men, the goal is simple: complete the most laps. How they do that, though, takes us back to Dineen's confusion, as the teams compete in six formats, sometimes as a pair, sometimes individually.

The madison,, external named after the venue that made it famous, provides the backbone and the teams do it twice a session.

A popular feature of the Olympic programme until its removal after the 2008 Games, this is the tag-race that sees one rider racing at the bottom of the track, while the other circles slowly at the top waiting for a hand-sling to propel them into the fray. The idea is to steal a lap on the rest, although there are also points on offer for intermediate sprints in the first of evening's madisons.

The other formats are all for the points that break any ties in the main contest.

The elimination race is an individual format, with the last rider to cross the line every second lap removed until two are left to fight out the points. The super sprint is similar except for the final being contested between six riders, not two.

Like keirin races at the Olympics, the derny and stayer formats involve individuals racing behind motorised bikes that provide big slipstreams, enabling the riders to reach high speeds for flying final laps.

And the team time trial is a two-lap effort the teams do one by one, one team-mate giving the other a madison-style sling to power to the line.

Simple, right?

But if you are struggling to keep score you could just order another beer, enjoy the lightshow and bounce along to the tunes from Ministry of Sound , externalDJ Martin 2 Smoove.

Who needs Wiggo?

So who, apart from Martin 2 Smoove, is performing?

Mark Cavendish, a partner in the business, will be there…but not on his bike. The injury he picked up at last month's Tour of Britain has not healed in time. Sir Chris Hoy, an event "ambassador", will also be there, but bikeless, and some observers have suggested this is a theme.

This perception is perhaps not helped by recently crowned European champions Sir Bradley Wiggins and Laura Trott, who are also not riding in London, agreeing to race the Revolution Series , externalevent in Manchester a day after Six Day London finishes.

Mark Cavendish teamed up with Belgium's Iljo Keisse, the most successful active six-dayer rider, to win the Ghent Six last year

But Madison Sports Group, external boss Mark Darbon denies his event lacks star quality.

He points to the 11 world champions, six European champions and two Olympic champions that are coming, not to mention Dame Sarah Storey.

In total, there are 65 riders on the programme, with Belgium's Iljo Keisse, Dutch star Niki Terpstra and British duo Adam Blythe and Dani King being the biggest draws.

"We are a new event finding our way in a crowded market but our field compares very well to any of the other six-day races in Europe," said Darbon.

"The timing is perhaps not perfect but we did not want to die wondering if this could work, so we have got on with it."

As ever, much will depend on ticket sales and Darbon is relatively happy with those. A quick look at the box office website suggests there are still plenty available but Thursday and Friday should be full.

"It's a show, an entertainment and the bike racing is just part of it," explained Hayles.

"Sure, the crowds in Ghent and Zurich were really into the racing, and get massively into it, but in Germany there was all kinds of stuff going on - jet-powered go karts, laser shows, circus acts - and the racing was a show before the nightclub opened."

It is hard to see London's organisers getting all that past health and safety but a clue as to where they want to position this event was provided when they recently bought the Berlin Six.

Because nobody is as serious about fun as the Germans. Or the Victorians, for that matter.

- Published12 October 2015

- Published16 October 2015

- Published1 December 2014

- Published23 November 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2016