Greece bailout: Varoufakis 'willing' as talks collapse

- Published

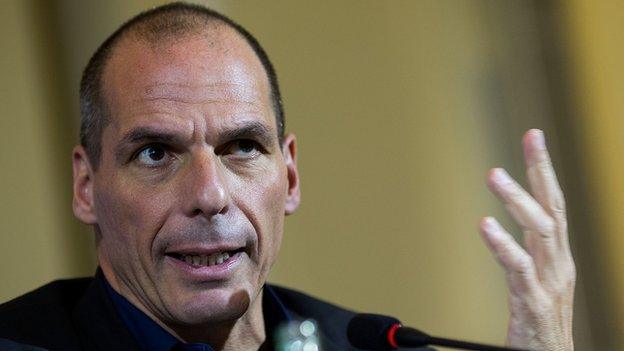

Yanis Varoufakis: "We are ready and willing to do whatever it takes"

Greece's Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis declared he was ready to do "whatever it takes" to reach agreement over its bailout after the collapse of talks with EU finance ministers.

Mr Varoufakis spoke after Greece rejected an EU offer to extend its current €240bn (£178bn) bailout, a plan he called "absurd" and "unacceptable".

He said he was prepared to agree a deal but under different conditions.

But the Dutch finance minister said there were just days left for talks.

Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who chairs the Eurogroup of finance ministers, said it was now "up to Greece" to decide if it wanted more funding or not.

"My strong preference is and still is to get an extension of the programme, and I think it is still feasible," Mr Dijsselbloem told a news conference after the talks collapsed.

Greece's current bailout expires on 28 February. Any new agreement would need to be approved by national governments, so time is running out to reach a compromise.

Without a deal Greece is likely to run out of money.

The Grexit explained - in 60 seconds

Mr Varoufakis said there was still "substantial disagreement" on whether the task ahead was to complete the current programme, which Greece's newly elected government has pledged to scrap.

He dismissed the promise of "some flexibility" in the programme as "nebulous" and lacking in detail.

Speaking at a news conference after Mr Dijsselbloem, he said he had been presented with a draft communique by Pierre Moscovici, the EU's economics commissioner, which he had been ready to sign.

However, that draft had been withdrawn minutes before the meeting started, Mr Varoufakis said.

But he sought to play down the setback as a temporary hitch.

"Europe will do the usual trick: It will pull a good agreement or an honourable agreement out of what seems to be an impasse.'"

Analysis: Andrew Walker, BBC economics correspondent:

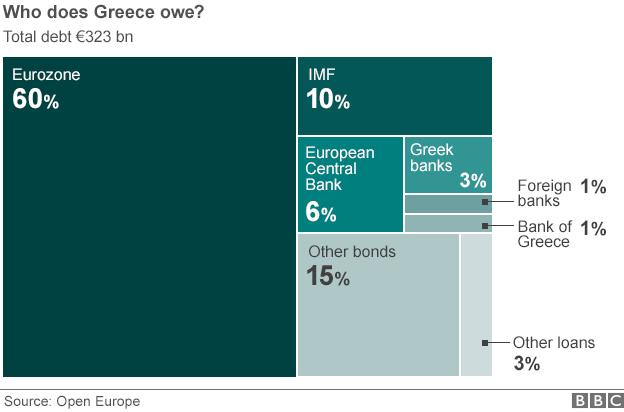

Two pressing financial issues loom over Greece: whether the government can pay its bills and the stability of the banks.

Greek officials have said the government could keep going for several months, but there are doubts. How long it takes depends to a great extent on Greek taxpayers.

The banks have already seen money being withdrawn and increasingly need central bank loans. If there is no bailout programme, the European Central Bank could pull the plug on the banks.

If it came to that, it really would mean a major financial crisis, with perhaps the imposition of extensive financial controls to prop up the banks and possibly even the re-introduction of a national currency.

It's hard to nail down a date by which an agreement must be done to avert some sort of financial Armageddon, because it depends on the actions of taxpayers, bank customers and the ECB. But time is getting short.

Key dates for Greece - and the eurozone

Before the meeting, German finance minister Wolfgang Schaeuble had already said he was not optimistic a deal would be reached.

The German finance minister insists that Greece needs to meet its pre-existing obligations

"The problem is that Greece has lived beyond its means for a long time and that nobody wants to give Greece money any more without guarantees," he said.

But French Finance Minister Michel Sapin said European leaders needed to respect the political change in Athens. As he arrived in Brussels he urged the Greeks to extend their current deal to allow time for talks.

Refinance

Greece has proposed a new bailout programme that involves a bridging loan to keep the country going for six months and help it repay €7bn (£5.2bn) of maturing bonds.

The second part of the plan would see the county's debt refinanced. Part of this might be through "GDP bonds" - bonds carrying an interest rate linked to economic growth.

Greece also wants to see a reduction in the primary surplus target - the surplus the government must generate (excluding interest payments on debt) - from 3% to 1.49% of GDP.

In Greece last week, two opinion polls indicated that 79% of Greeks supported the government's policies, and 74% believed its negotiating strategy would succeed.

- Published17 February 2015

- Published16 April 2015

- Published6 July 2015

- Published12 February 2015

- Published11 February 2015

- Published8 February 2015