Why the world's biggest investor backs the simplest investment

- Published

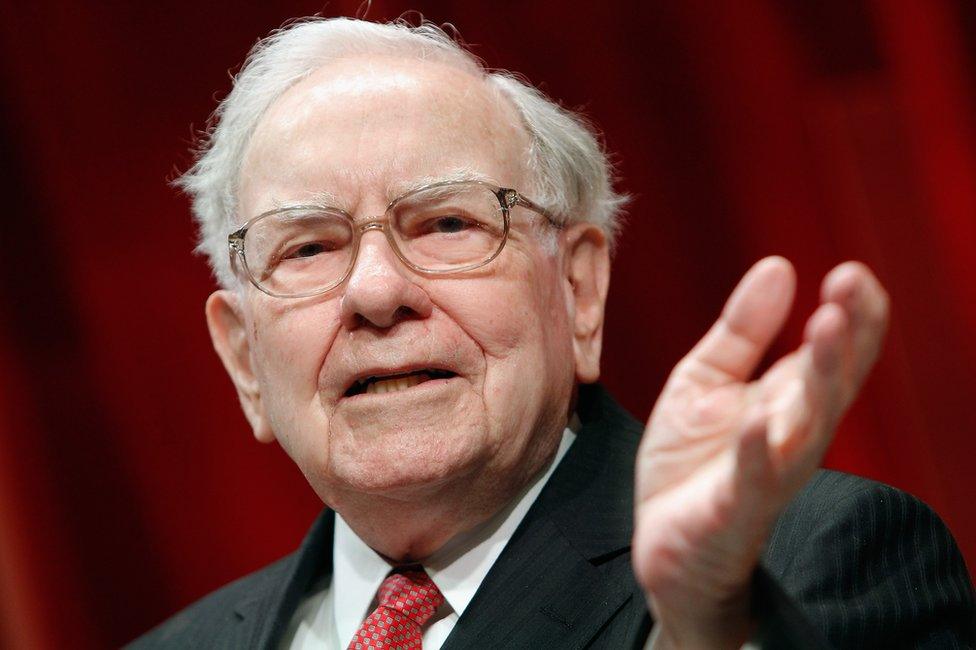

Warren Buffett has advised his wife to put her money into simple index funds after his death

What's the best financial investment? If anyone knows, it's Warren Buffett, the world's richest investor.

He's worth tens of billions of dollars, accumulated over decades of savvy investments. His advice is in a letter he wrote to his wife, advising her how to invest after his death, which anyone can read [page 20, paragraph 6], external.

Those instructions: pick the most mediocre investment you can imagine. Put almost everything into "a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund".

An index fund is mediocre by definition. It passively tracks the stock market as a whole by buying a little of everything, rather than trying to beat the market by investing in individual companies - as Warren Buffett has done so successfully for more than half a century.

Bright idea

Index funds now seem completely natural. But as recently as 1976, they didn't exist.

Before you can have an index fund, you need an index.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

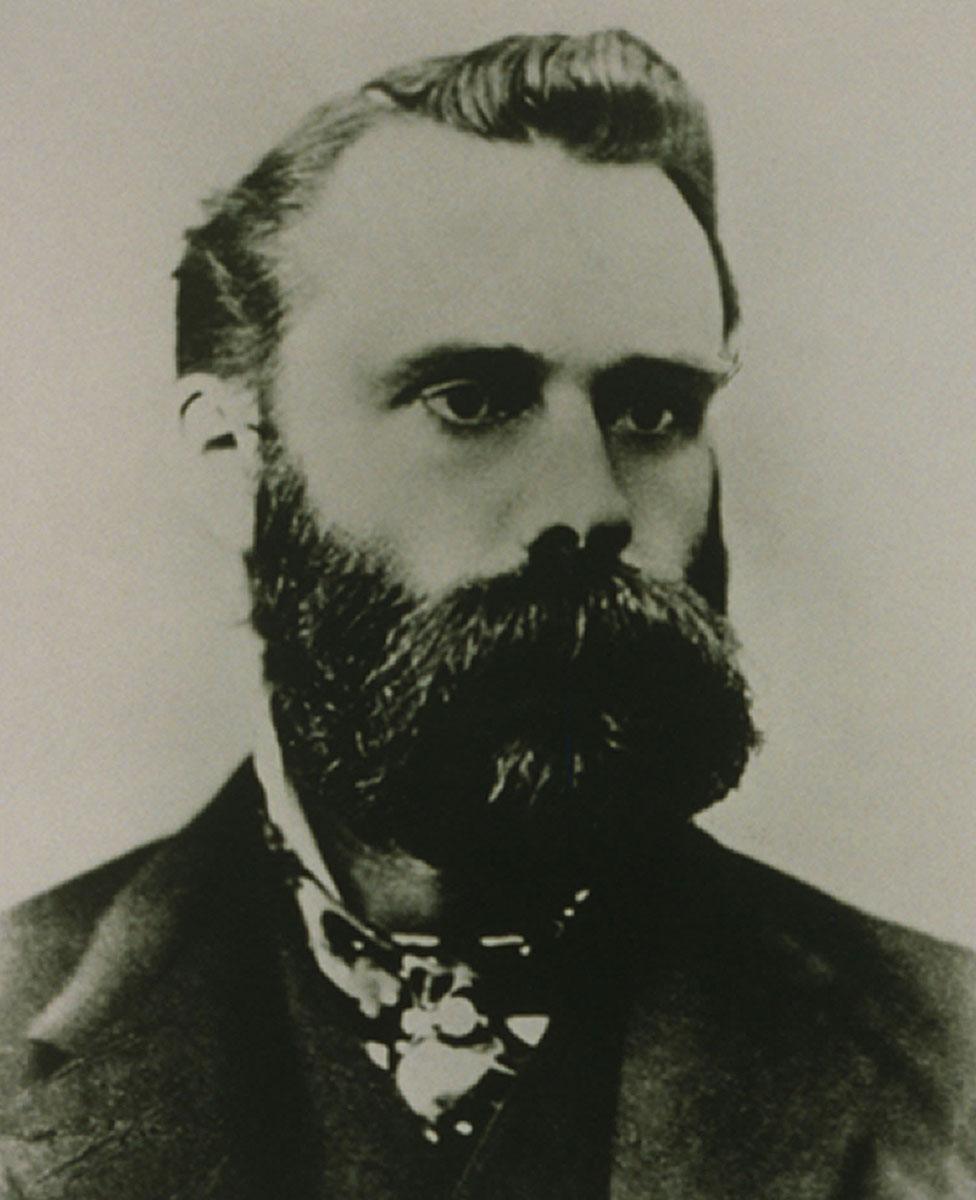

In 1884, a financial journalist called Charles Dow had the bright idea to take the price of some famous company stocks and average them, then publish the average going up and down.

He ended up founding not only the Dow Jones company, but also the Wall Street Journal.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average didn't pretend to do anything much except track how shares were doing, as a whole.

Charles Dow's first Industrial Average tracked the closing stock prices of 12 companies

But thanks to Charles Dow, pundits could talk about the stock market rising by 2.3% or falling by 114 points.

More sophisticated indices followed - the Nikkei, the Hang Seng, the Nasdaq, the FTSE, and most famously the S&P 500. They quickly became the meat and drink of business reporting all around the world.

Then, in 1974, the world's most famous economist took an interest.

Paul Samuelson had revolutionised the way economics was practised and taught, making it more mathematical and engineering-like, and less like a debating club.

His book Economics was America's bestselling textbook in any subject for almost 30 years. He won one of the first Nobel memorial prizes in economics.

Efficient markets

Samuelson had already proved the most important idea in financial economics: that if investors were thinking rationally about the future, the price of assets such as shares and bonds should fluctuate randomly.

That seems paradoxical, but the intuition is that all the predictable movements have already happened: lots of people will buy a share that's obviously a bargain, and then the price will rise and it won't be an obvious bargain any more.

His idea became known as the efficient markets hypothesis.

Paul Samuelson (left) received the 1996 National Medal of Science for his contribution to economic science

It's probably not quite true. Investors aren't perfectly rational, and some are more interested in covering their backsides than taking well judged risks. But the hypothesis is true-ish. And the truer it is, the harder it's going to be for anyone to beat the stock market.

Samuelson looked at the data and found - embarrassingly for the investment industry - that, indeed, in the long run, most professional investors didn't beat the market.

And while some did, good performance often didn't last. There's a lot of luck involved, and it's hard to distinguish that luck from skill.

In his essay Challenge To Judgment, external Samuelson argued that most professional investors should quit and do something useful instead, such as plumbing.

He also said that, since professional investors didn't seem to be able to beat the market, somebody should set up an index fund - a way for ordinary people to invest in the stock market as a whole, without paying a fortune in fees for fancy professional fund managers to try, and fail, to be clever.

Then, something interesting happened: a practical businessman paid attention to an academic economist's suggestion.

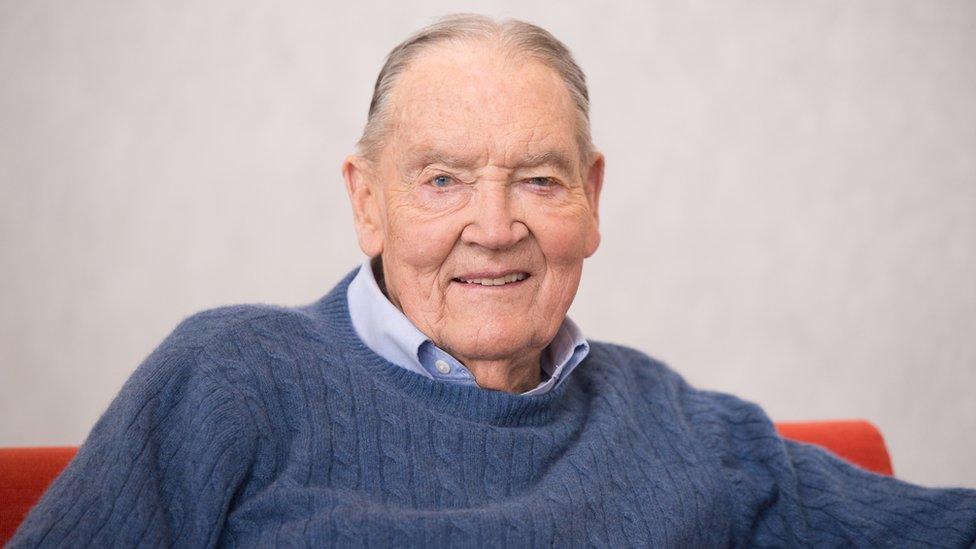

John Bogle had just founded a company called Vanguard, whose mission was to provide simple mutual funds for ordinary investors, with no fancy stuff and low fees.

'Bogle's Folly'

And what could be simpler and cheaper than an index fund - as recommended by the world's most respected economist?

So Bogle set up the world's first index fund, and waited for investors to rush in.

Investors were initially slow to put their money into John Bogle's index funds

They didn't. When Bogle launched the First Index Investment Trust, in August 1976, it flopped.

Investors weren't interested in a fund that was guaranteed to be mediocre. Financial professionals hated the idea - some even called it "un-American".

It was certainly a slap in their faces. Bogle was effectively saying: "Don't pay these guys to pick stocks, because they can't do better than random chance. Neither can I, but at least I charge less." People called Vanguard's index fund "Bogle's Folly".

But Bogle kept the faith, and slowly people started to catch on.

More from Tim Harford

Active funds are expensive, after all. They often buy and sell a lot, in search of bargains. They pay analysts handsomely to fly around meeting company directors. Their annual fees might sound modest - just a percent or two - but soon mount up. Eventually, fees can swallow a quarter or more of a typical fund.

Hope over experience?

If such funds consistently outperform the market, that's money well spent. But Samuelson showed that, in the long run, most don't.

The super-cheap index funds looked, over time, to be a perfectly credible alternative to active funds - and much cheaper.

Today 40% of US stock market funds are passive trackers rather than active stock-pickers

Slowly and surely, Bogle's funds grew and spawned more and more imitators - each one passively tracking some broad financial benchmark or other, each one tapping into Samuelson's basic insight that if the market is working well, you might as well sit back and go with the flow.

Forty years after Bogle launched his index fund, fully 40% of US stock market funds are passive trackers rather than active stock-pickers. You might say that the remaining 60% are clinging to hope over experience.

Index investing is a symbol of the power of economists to change the world that they study.

When Samuelson and his successors developed the idea of the efficient markets hypothesis, they changed the way that markets themselves worked - for better or worse.

It wasn't just the index fund. Other financial products, such as derivatives, really took off after economists worked out how to value them.

Samuelson ranked the invention of the index fund alongside Gutenberg's printing press

Some scholars think the efficient markets hypothesis itself played a part in the financial crisis, by encouraging something called "mark to market" accounting - where a bank's accountants would work out what its assets were worth by looking at their value on financial markets.

There's a risk that such accounting leads to self-reinforcing booms and busts, as everyone's books suddenly and simultaneously look brilliant, or terrible, because financial markets have moved.

Samuelson himself, understandably, thought that the index fund had changed the world for the better.

It's already saved ordinary investors literally hundreds of billions of dollars.

For many, it will be the difference between scrimping and saving or relative comfort in old age.

In a speech in 2005, when Samuelson himself was 90 years old, he gave Bogle the credit.

He said: "I rank this Bogle invention along with the invention of the wheel, the alphabet, Gutenberg printing, and wine and cheese: a mutual fund that never made Bogle rich, but elevated the long-term returns of the mutual-fund owners - something new under the Sun."

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published28 June 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published18 March 2016

- Published5 March 2017

- Published17 March 2015