Stirling Prize: Newhall Be

- Published

Stirling Prize judges say Newhall Be raises the bar in terms of commercial house building. But why is this development so different, and what does it tell us about the modern home?

Newhall Be in Harlow is a prototype for more interesting commercial house building. It is a suburban development with a very un-suburban nature. The windows are large, the ceilings are high and the walls are black.

"We tried to make homes that have some joy, that feel a bit like you are on holiday," says the architect, Alison Brooks.

"We wanted to offer people some choice, to show them that there are different types of homes to live in."

Traditional houses are based around pitched roofs and brown bricks. It is safe, and it sells. But Brooks believes people want more than that.

Also in the running are Astley Castle, Bishop Edward King Chapel, Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre, Park Hill Phase 1 and University of Limerick Medical School.

"There's the conventional box that has mean little windows punched into the sides," she says.

"It is so stripped of any character that they have no identity. Developers build them because they know they can sell them. But there's such a shortage of homes that anything will sell, people buy them out of desperation."

UK homes are the smallest in western Europe, according to a report by the Future Homes Commission (FHC), external. And where minimum space standards are applied, they fall below the guides set in neighbouring countries.

"A space can make you suffer," says Brooks. "If there is a lack of light, a lack of space, if it is poorly organised - then you're miserable."

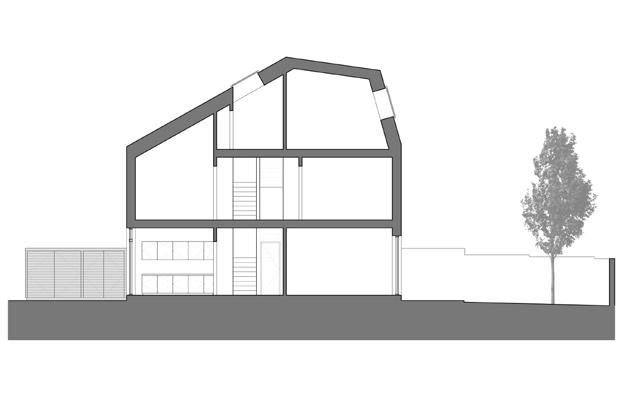

The emphasis at Newhall Be is on space, light and adaptability. The ground floor office could be used as a bedroom or games room. The cathedral-style roof could be converted into an extra bedroom.

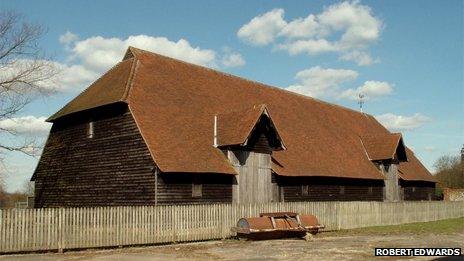

The black weatherboarding was designed to give a distinct local identity, echoing the barns that adorn the Essex countryside.

"There is a presupposition by house builders that we want a very traditional looking house," says Maxwell Hutchinson, architect and broadcaster.

"They think we want brickwork, timber windows, pitched roofs and a garden at the front and rear. But actually we want more than what is served up on their menus. We want something different."

The report by the FHC, external cites natural light and large rooms as among the key demands from 21st Century housing. Storage and an ability to adapt a home to different layouts and family scenarios also rated highly. Unimaginative design was criticised.

"The typical home being built in the UK is uninspiring," the report said. "Too little thought is given to design, there is a lack of innovation and choice is poor."

Newhall Be - so called because it is a place to "just be" and it's the "place to be" - consists of 84 houses built on land that belonged to brothers Jon and William Moen, who inherited their grandfather's farm.

Brooks's Be is part of a wider Newhall development. There are another 60 homes - Newhall North Chase and Newhall Slo - by other architects that have also drawn praise for enlightenment in their design.

The black-clad homes visually echo the barns of Essex

The Moen brothers' first venture into development disappointed them.

Church Langley, which is adjacent to Newhall, was sold to a developer consortium, external and the brothers later described the results as dull.

With Newhall they were more hands on, cherry-picking architects who shared their vision for modern living and employing town planner Roger Evans to create a new network of roads, homes and green spaces.

Evans began by overlaying street plans of Venice, Bath, Oxford and other historic towns onto a plan of the Newhall site. They were his examples of successful high-density towns, and from them, Newhall was developed.

The plot was divided into sections. Each would have its own architect and the emphasis was on design quality.

Gardens have been squeezed...

... to fit more homes onto the site

Houses at Newhall are high in density, but the communal green spaces are generous - about 40% of the area.

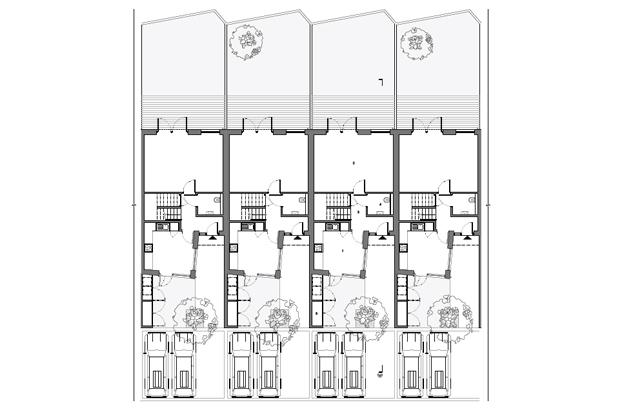

Brooks has packed her homes even tighter. Original planning permission was for 76 homes, but by halving the gardens and adding roof gardens to replace the land lost, she has shoehorned in another eight.

"It's a tricky move because family homes need gardens," says Kate Faulkner, of the Future Homes Commission.

"If I had young children I wouldn't want them playing on a roof garden. Most people would want a lawn and space, but I guess the communal space compensates for that."

The benefit was that there was more money to spend on each one.

A two-bedroom house at Newhall Be costs about £240,000, three-bed houses go for about £300,000. All were sold within 16 months.

It is Brooks's hope that mortgage lenders and valuers will one day count design and quality on their list of criteria, rather than valuing homes purely on the number of bedrooms and precedent.

Then she believes developers would have more incentive to improve on quality.

"The economics of house building doesn't have any incentive," says Brooks.

"Some developers even call their homes products, which I really disagree with. The places where people live their lives are deserving of our most sincere efforts."

Evolution of the design

3D plan of Newhall Be

Hybrid aerial plan of Newhall Be

Long view of terrace house

Ground floor plan of terrace houses

Video by: John Galliver

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external