Stirling Prize: Astley Castle

- Published

The ruins of Astley Castle have been turned into a modern holiday home. Is this an acceptable approach to conservation?

Astley Castle is a medieval ruin with under-floor heating and power showers. There are still crumbling stones, now eroded by weeds, but modern engineering has made it solid, and perhaps more importantly, comfortable.

It is a modern two-story house within the relic of an ancient castle.

It is believed Lady Jane Grey may have once walked the floors - ghost stories say she still does. Now it is a holiday home for those seeking historic drama and modern convenience.

But does the merging of olden days cragginess and contemporary slickness show great pragmatism - retaining history but making it work for us - or should old buildings be more faithfully restored?

The visitors' book gushes with congratulations.

"The new interior dovetailed so skilfully into the exterior works brilliantly," writes one visitor.

Also in the running are Bishop Edward King Chapel, Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre, Newhall Be, Park Hill Phase 1 and the University of Limerick Medical School.

"We have been delighted with the amalgamation of ancient and modern," wrote another.

"A building oozing in commodity, firmness and delight," it continues.

The only comment criticising the fixtures and fittings as being "out of place" incites another visitor to add an asterisk and a sarcastic riposte: "Showers… toilets… running water have no place in a building of this age. Remove immediately."

Even proponents of the radically modern still often love an old facade.

Take the AA School of Architecture, famed for its radical approach to building design. It's based in a row of classic Georgian terraces in Bedford Square, London.

The architect behind Paris's inside out Pompidou Centre, Richard Rogers, is famous for designing modernist buildings, yet lives in a grade II-listed Georgian town house.

But there are many places where historic exteriors mask very modern interiors.

"It's about space and light, that's what people like now," says Financial Times architecture critic Edwin Heathcote.

"To achieve that whilst keeping a sense of time and history is clever - it makes sense. There's certainly no dishonesty."

Heathcote describes the redevelopment of Astley Castle, near Nuneaton, as "poetic".

But for others it is history lost.

"It was all dark wooden panels and very medieval looking," says Nuneaton historian Peter Lee, who used to visit the castle in the 1960s, when it was run as a hotel and restaurant.

"It was dark and dingy and quite creepy. There was a very rude parrot that used to say naughty words and a Great Dane the size of a man who used to sleep in the corner. Ghosts too apparently, and some strange parties."

But Lee concedes it would not have been to everyone's tastes.

"Most people don't like dark and creepy," he says. "I guess the important thing is that it's back in use. But as a historian, I felt disappointed."

A time capsule of bricks down the ages in the enclosed courtyard

The moated fortified manor house gained Grade II listed status in 1951

The moated castle dates back to the Saxon period and has been associated with some of the nation's most turbulent periods of history.

The Grey family were the castle's most famous owners, taking control from 1420 to 1600.

Through them, the castle has links to three queens of England - though they may or may not have actually been there. Astley was the Grey's secondary manor - a holiday home then, as it is now.

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV, was the first queen. She had owned the castle with her first husband Sir John Grey, who died fighting for the Lancastrians in the War of the Roses.

The resourceful widow is believed to have lain in wait under a tree for the king to plead for help for her young sons' future. When he arrived he fell immediately in love and they were married.

Their daughter, Elizabeth of York, became Astley's second queen through her marriage to Henry VII.

And their great granddaughter Lady Jane Grey was the last. A queen for just nine days, she was ousted by Mary I and later beheaded for treason at the Tower of London.

Astley Castle came into the spotlight when her father, the Duke of Suffolk, reportedly hid in the hollow of an oak tree in the grounds as he tried to evade capture following a rebellion in 1554 against Mary's betrothal to the Catholic Philip of Spain. He was found, and later executed for treason. Though the tree blew down in 1891, the spot is now marked by a memorial stone.

Some centuries later, the novelist George Eliot grew up on the estate.

But in 1978 the castle burned down. For the next 30 years it was left a crumbling ruin, uninhabitable until this redevelopment.

"There is a strong heritage lobby whose view is that you should restore something very studiously, faithful to one moment in time," says Stephen Witherford, of the project's architects Witherford Watson Mann.

"Another school of thought is that you can touch it with a bit of glass very delicately, keeping an overt contrast between old and new.

"But both of these approaches take history as a fixed thing, almost making an object out of it. Astley wasn't of a single period. It had been altered almost continually over 800 years."

More than a conservation project, it is a reinvention of the ruins

The building is now snug, and secured against the elements

Astley is run by the Landmark Trust, a heritage organisation that rents out old buildings as holiday homes.

The trust took on a 99-year lease on the building, which is part of the Arbury Estate, and commissioned the redevelopment with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund, English Heritage and a large philanthropic donation.

They launched a competition with the simple brief - create a four-bedroom house to sleep eight people at Astley Castle.

"It didn't give us very much," says Witherford. "They were apparently a few different approaches. Some had a new house in the grounds, and had the castle as a garden. Others kept the facade but built a completely new house behind it."

The winning design was more hands-on. They built into the castle, using slim bricks to fuse with the jagged edges of the ruin. The structure was left intact and on show, and the gaps were filled.

"We didn't want to make something that you just looked at, it had to be much more of an experience. We wanted you to actually live the building and feel all of its history," he adds.

The conventional house arrangement has been flipped, with the bedrooms on the ground floor and the kitchen and living area upstairs. Large modern windows frame the views.

Outside two open courtyards have been strengthened and safeguarded from the elements, but visually left as a ruin. A dining table fills one, and they are divided by a chimneystack, which can be used for al fresco cooking.

There are more subtle nods to the history in the furnishings. There is no television, for example. And portraits of historic characters including Henry VIII and Jane Seymour peer down from the walls and over beds, reminding visitors just how old Astley is.

"They've not made a fuss about it, there are no acrobatics," adds Heathcote. "They have just crafted something beautiful out of something that was crumbling."

Evolution of the design

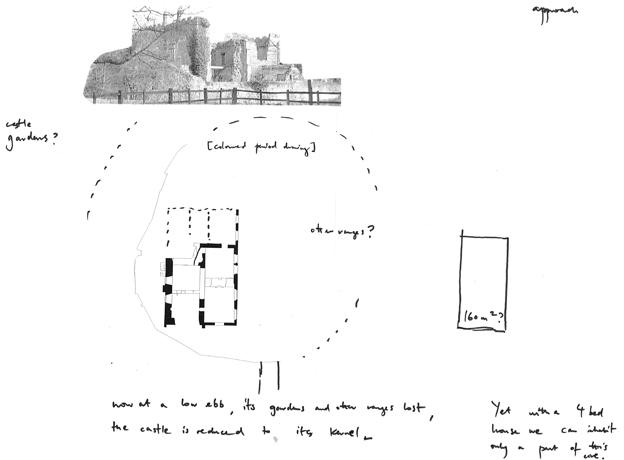

An early sketch with photograph of the ruins: "Now at a low ebb, its gardens and other ranges [wings] lost, the castle is reduced to its kernel - yet with a 4-bed house, we can inhabit only a part of this core"

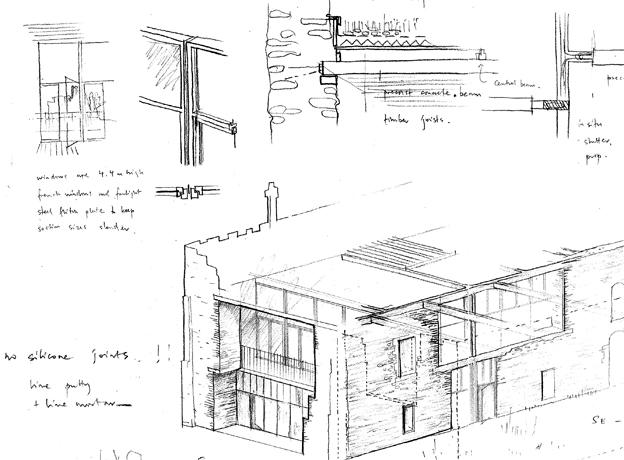

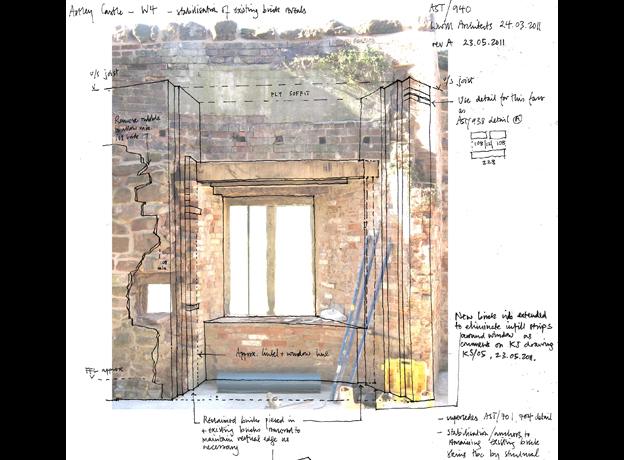

Details of the materials used, such as steel for the 4.4m high windows, and how to make joins between old and new - "no silicon joints!" reads one note

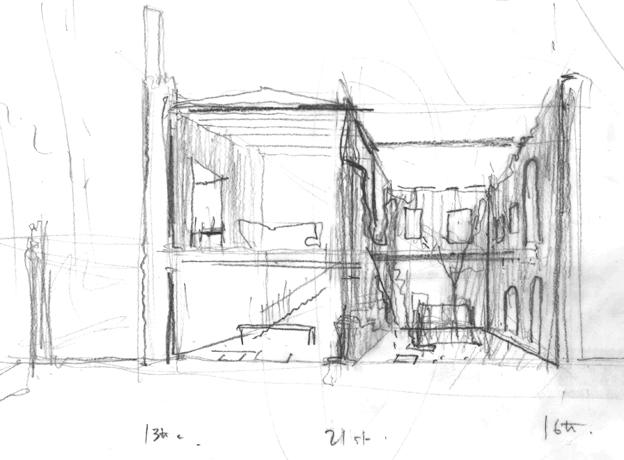

A cross-section of the castle, annotated to show the ages of the building - 13th Century on the left, the 21st Century interior and a 16th Century wall on the right

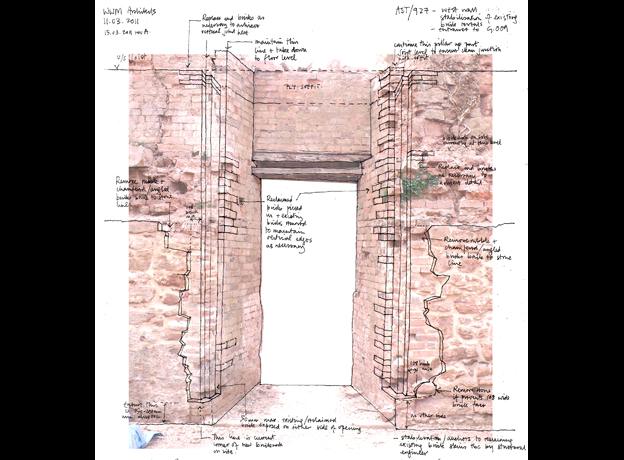

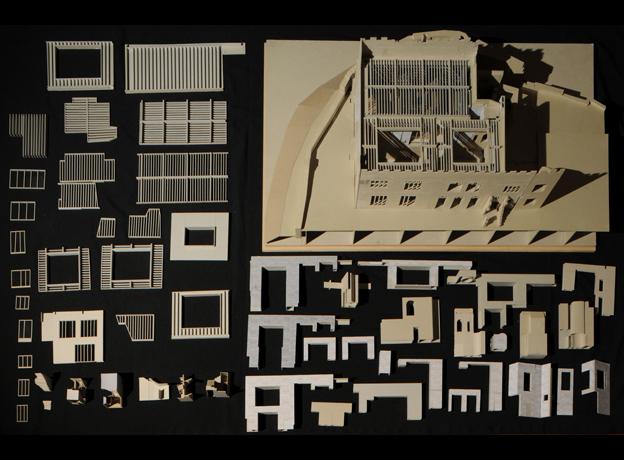

The architects made about 100 masonry drawings to explain to the bricklayers all the variations in how the new walls should meet the existing brickwork, and exactly where each reclaimed brick should go

Where loose Georgian brickwork joined medieval rubble walls, the architects designed stepped brickwork details in the new bricks to provide additional stabilisation of the ruin

This model was used to test many different options for how the new walls could be integrated into the existing ruins, says architect Freddie Phillipson

The model was also tested under an artificial sky to show light levels at different times of day and year - and to demonstrate that the courtyards would be bright even with a perimeter roof

Video by: John Galliver

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external