Stirling Prize: Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre

- Published

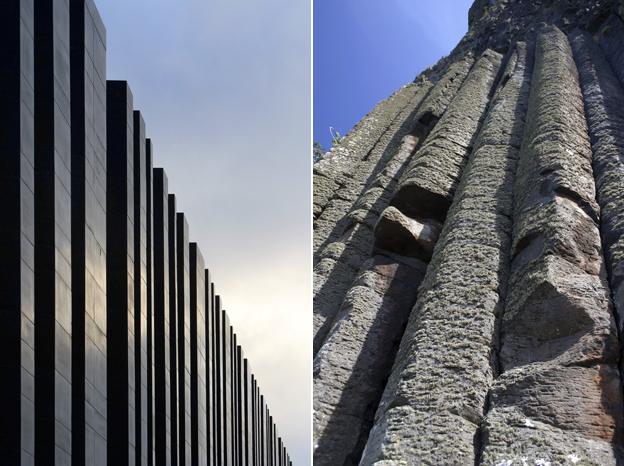

From one side it is basalt columns and shiny glass. From the other it is a grassy bank, barely seen at all. The Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre is an attempt to balance buildings with the environment.

It is meant to look like it has been pulled up from the earth. The basalt columns rise into the air, echoing the famous stones of the Causeway.

One part of the building protrudes from a sloping grass bank, while the other disappears down into the same earth, shielding the car park from view.

The new visitor centre at the Giant's Causeway is self-effacing in its attempt to fit in with the scenery. It could not distract from the landscape it was built to showcase.

From the Causeway it cannot be seen at all.

But the repeated smooth dark columns, some 6m tall, are monumental in stature.

Also in the running are Astley Castle, Bishop Edward King Chapel, Newhall Be, Park Hill Phase 1 and the University of Limerick Medical School.

"We were always very aware that the reason for this project was to facilitate what was around it," says Roisin Heneghan, of Heneghan Peng architects.

"We felt quite strongly that when someone arrived at the site they should see the landscape and not the building."

The centre, which houses a cafe, exhibition space and a shop, is largely underground.

Roof lights draw in daylight and give people "a sense of the environment outside", says Heneghan.

The rain and wind of the North Antrim coast thrashes against the glass, reinforcing the wildness of the landscape.

Outside, visitors can walk over the sloping grass roof, stepping on the ceiling windows and peering down to the shiny concrete inside the building.

The basalt, a hard, dark rock formed from quick-cooling volcanic lava, was quarried from a site 20 miles away. It is a material more usually found in country walls and hardcore beneath the road surface, but it matches the basalt of the Causeway's 40,000 hexagonal stones.

"The columns were almost accidental really," says Heneghan.

"It wasn't so much an attempt to echo the Causeway - more the nature of the material that we used. The basalt has a lot of cracks in it and there is a maximum size that you can use in a certain area. That's what drove the design."

At £18.5m and a decade in the planning, the centre was long awaited. Its predecessor was a temporary hut, which had stood for 12 years on the clifftops overlooking the Causeway. The original centre burned down in 2000 after an electrical fault.

But wrangling had delayed the project. Heneghan Peng had won the contract to design the building in 2003. It was to be a publicly funded scheme, commissioned by the Department of Enterprise Trade and Investment in Northern Ireland. But businessman Seymour Sweeney submitted his own plans for the site, fuelling a private versus public sector debate.

His scheme almost won approval - but then didn't, external. Legal disputes ensued and the National Trust took on the Heneghan Peng plans and pushed them forward.

"The Giant's Causeway is Northern Ireland's most famous place. It's also our only World Heritage Site, so it was a huge responsibility," says Heather Thompson, director for the National Trust in Northern Ireland.

"We worked with a huge team of people to create something which acts as the perfect gateway. I think it reflects the landscape very well and it creates a real sense of arrival."

Walking on the ceiling windows

Since opening, the centre has received its share of criticism. The £8.50 entry fee has been described as excessive, external - the stones themselves, believed to have been formed by a volcanic convulsion, have always been free to see.

The National Trust was also forced to revisit part of its exhibition, which was accused of promoting the views of Young Earth Creationists, that the Causeway was created some 6,000 years ago. The vast majority of scientists say it was formed 60m years ago.

The National Trust said it had been a "misunderstanding", and that they only endorse the scientific explanation of the origins of the stones.

And most recently, the trust lost its legal bid to halt the development of a golf course with a five-star, 120-bedroom hotel and 75 villas on adjacent land because of its close proximity to the site.

But more than 780,000 visitors have passed through the centre since it opened just over a year ago. And it has contributed to a burgeoning architectural scene in Northern Ireland.

Inside the visitor centre

The Lyric Theatre in Belfast was nominated for the 2012 Stirling Prize - it lost to Stanton Williams' Sainsbury Laboratory. And the MAC performing arts centre, also in Belfast, narrowly missed out, external on this year's shortlist.

"I've been writing about new buildings for 10 years and it is not until two years ago that I have ever had cause to go to Northern Ireland," says Ellis Woodman, editor of Building Design magazine.

"The visitor centre is part of something very exciting. I think it must achieve everything it set out to do."

It's the role of the centre to guide visitors and give them a place to convene. It also manages traffic - the car park is arguably one of the most important elements of the development, protecting the surrounding environment from thousands of cars.

Evolution of the design

The slopes echo the Causeway's descent into the sea (photos Marie-Louise Halpenny and Thinkstock)

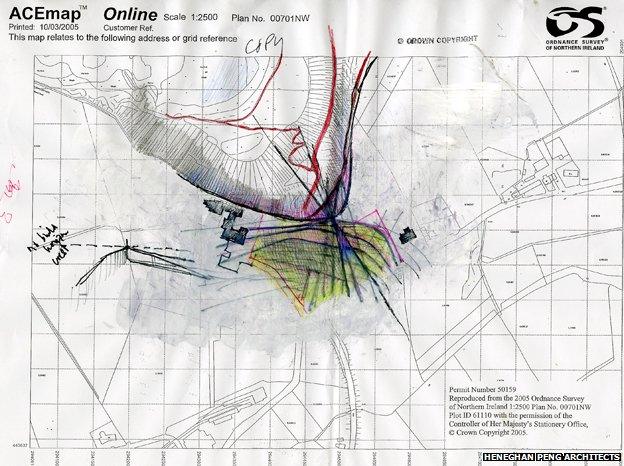

Early sketch on an OS map - the architects wanted visitors to "see the landscape, not the building"

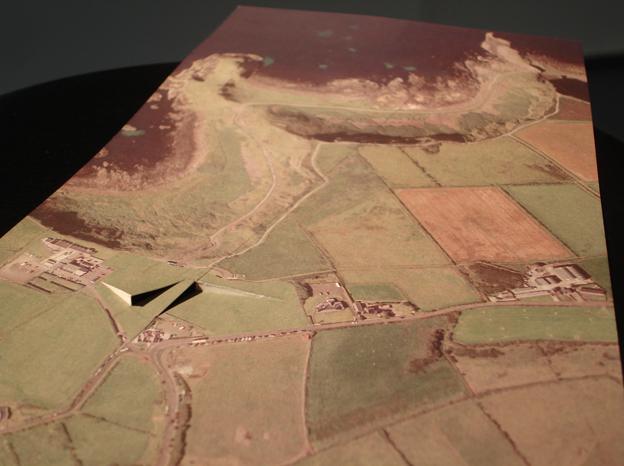

An architect's model of the centre emphasises the way it blends into its environment

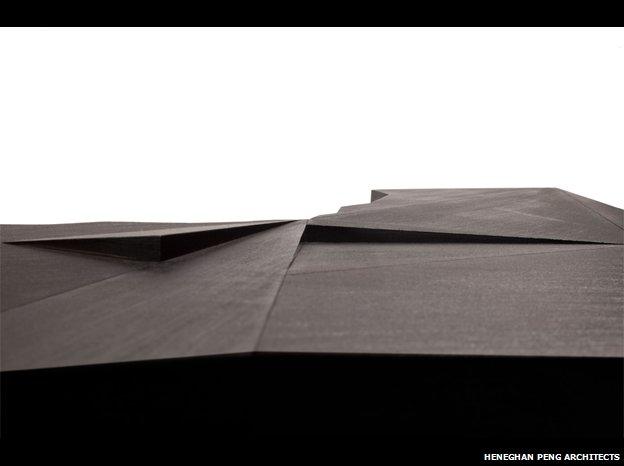

... as does this architect's model

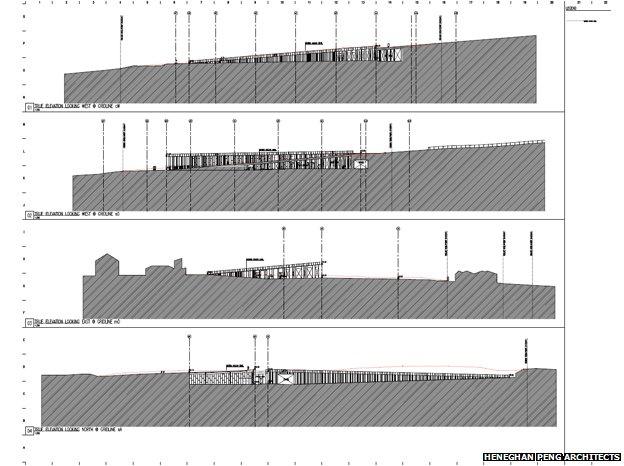

Cross-section of the visitor centre - low-lying, it barely interrupts the slow descent of the land to the sea

The resemblance is a "happy coincidence", say the architects (photos Hufton+Crow and Thinkstock)

Video by: John Galliver

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external