Stirling Prize: Bishop Edward King Chapel

- Published

The elliptical Bishop Edward King Chapel is the place of worship for an order of nuns and 250 student clergy. But how do you make a brand new building spiritual?

Worshippers, both of the religious and architectural kind, enter through a dark hallway.

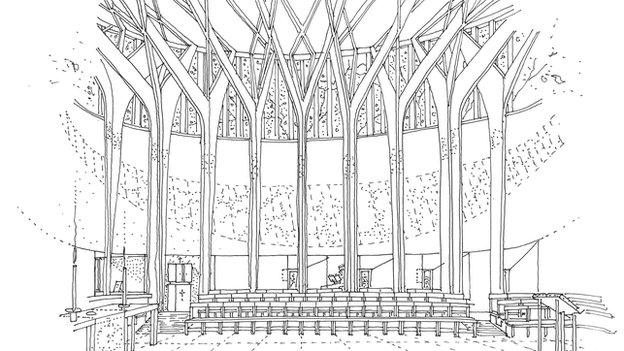

There are three steps down to the polished floor of the chapel, but above, the latticed woodwork draws the eye towards high windows with dappled light from the surrounding trees.

"It raises you up like a kite," says Rev Martyn Percy, the principal of Ripon College in Cuddesdon.

"The idea that you are grounded and yet lifted up was extremely profound for us. It shows a very implicit understanding of what we wanted."

Also in the running are Astley Castle, Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre, Newhall Be, Park Hill Phase 1 and the University of Limerick Medical School.

The chapel, which stands at the centre of the college in the Oxfordshire countryside, is dramatic and subtle, modern and yet crafted from natural materials.

"It's like being bathed in numinous buttermilk," adds Percy, who describes himself as the apostle of anti-tat. "It feels slightly amniotic. You are immersed in this space of pure, clear, confident light."

Part of the inspiration for the building was a play on the word nave. As well as referring to the main part of a church, nave is derived from the Latin word for boat, and also refers to the hub of a wheel and to the navel - conjuring ideas of umbilical cords or place of origin.

"It is the bit that doesn't move, everything else swirls around it. This is a place of stillness and watchfulness. This is a place where people come to gaze," says Percy.

Its elliptical shape was a key starting point for the design

Costing £2.6m, the chapel took 18 months to build. It was designed by Niall McLaughlin Architects and opened in February. It is used by the Ripon College community, as well as the Sisters of Begbroke, an order of nuns based at the college.

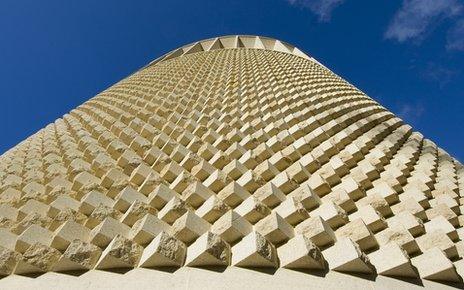

The outside wall is made of Clipsham stone arranged in a dogtooth style, with alternate rough and smooth edges facing outwards. Each one was individually snapped using a handheld tool.

Larch and ash woods are used in the furniture and beams, providing subtle variations in tone. The walls and ceiling, rendered in lime plaster, show equally subtle variations in textures and shade.

"The plasterers were lying down on their backs to do the ceiling like Michelangelo," says McLaughlin.

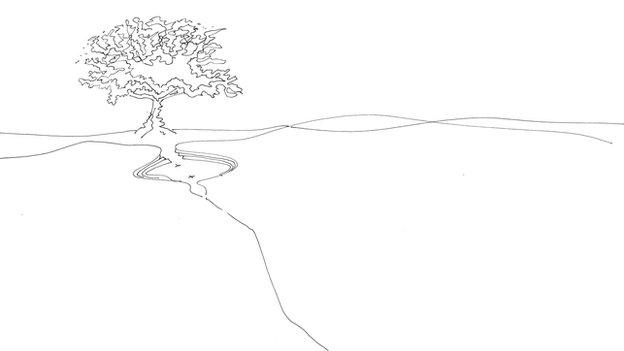

The ellipse shape achieves another layer of symbolic detail. On one side the window protrudes exactly between two trees, offering the only uninterrupted view across the valley. On the other, the doorway - wooden, heavy and almost a foot thick - is aligned with the trunk of a huge copper beech tree.

"Much like when people come out of the cinema and it feels like they've been immersed in one world and are coming out into another, that's what I wanted from the chapel," says McLaughlin. "I wanted people to come out underneath the protective canopy of the beech."

Trees are a recurring theme. They surround the chapel, they fill the views from every window and their dappled light creates a soft and nuanced light - like moving stained glass.

Inside the building, sweeping wooden arches rise up to the ceiling. They are the trees, the gothic arches and a whisper of the ship.

"There is so much metaphor in this chapel," says Edwin Heathcote, architectural critic for the Financial Times.

"It has all these layers of imbued meaning, perhaps there are too many. Maybe they tried too hard. But it works. It's a very pure kind of architecture. It would have been a dream commission."

Plasterers lay on their backs to render the ceiling

Beams and furniture are made from larch and ash wood

The college is, as Percy calls it, a "vicar factory" or a "holy Hogwarts". The students are in training to become clergy and live a slightly monastic existence with long periods of silence.

For 160 years the college has fallen silent from 22:30 to 08:30. The day starts at 07:15 when people join together silently. At 07:30 it is morning prayer followed by the Eucharist at 08:00. Breakfast, and finally talking, comes at 08:30.

So when voices are heard, they must be heard with crystal clarity.

Percy describes the acoustics inside the chapel as "seeping through your skin and into your soul". The effect was achieved with some unusual techniques.

"We wanted acoustics that suited a single speaking voice and a group of singing voices, so that when people sing together they have the confidence to sing more," says McLaughlin.

"We made a hat that was about the size of a wedding cake and it had headphones attached. It was like a model of the chapel and it meant we could test the acoustics and show people how it was going to sound, it was rather fun."

McLaughlin says the results help to achieve that "intuitive sense of a church".

"It's the way they sound, the way they feel. It's that instinctive feeling that this is a spiritual place."

Religion has historically inspired great architecture, but of the splendid kind, like the golden ceiling of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, or the intricate spires of Gaudi's Sagrada Familia.

Bishop Edward King Chapel is more muted.

"It beautifully understates the textures of our lives and faith," says Percy. "It is subtle and nuanced. It is a pure space where people can come to just sit."

Evolution of the design

Trees surround the chapel and have been used for interior beams and furniture

Latticed woodwork draws the eye upwards to high windows, reflecting the spiritual experience

A space for contemplation allows visitors to sit and enjoy a rural view

All pictures courtesy of Niall McLaughlin Architects

Video by: John Galliver

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external