Memories of Becontree council estate 100 years on

- Published

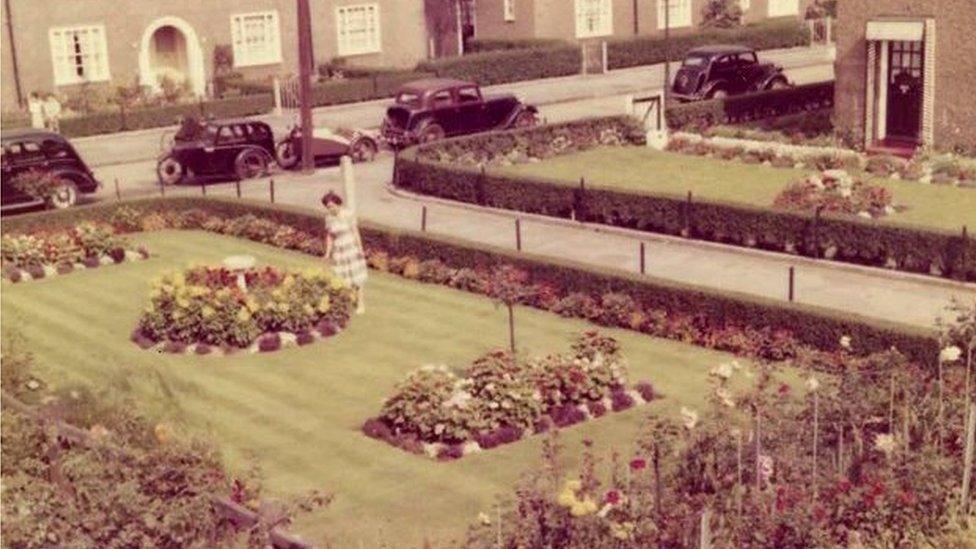

Residents competed every year to win the best kept garden competition

Crescents, cul-de-sacs and indoor toilets were but a dream for the residents of London's slums in 1919. But thanks to chancellor Lloyd George's revolutionary scheme to make "homes fit for heroes", Becontree - the first and largest council estate in the UK - made those fantasies a reality. A century later, its residents reflect on living in a "working class haven".

"Those who watched the construction of Becontree were immediately filled with hope of a new world," says Peter Fisher, who has lived on the estate for 92 years.

"These people watched with wonder and excitement as a new era - of luscious homes that had running water, indoor toilets and private gardens - was created.

"For them, the days of slumming it in the East End were over."

Peter's family was one of the first to move into Dagenham's newly built estate in east London, taking up residence in 19 Chitty's Lane. At the age of four, he recalls his mother telling him they were "going on an adventure to a new life, away from disease and plague."

"My parents, my four brothers and I moved from a two bedroom flat in Whitechapel to Chitty's Lane in 1926. It was a few doors down from number 26 - the first house built in Becontree.

"Our house was gigantic - it had a big kitchen, a well-kept garden that ran all the way around the back and the front. I was the king of the castle. As far as my mum was concerned, it was heaven - though she had difficulty making a house look a home with our somewhat meagre possessions.

"She loved having the simplest of things - like kitchen cupboards and a stove. She'd never let me open the fruit cupboard in case I got dirt on it."

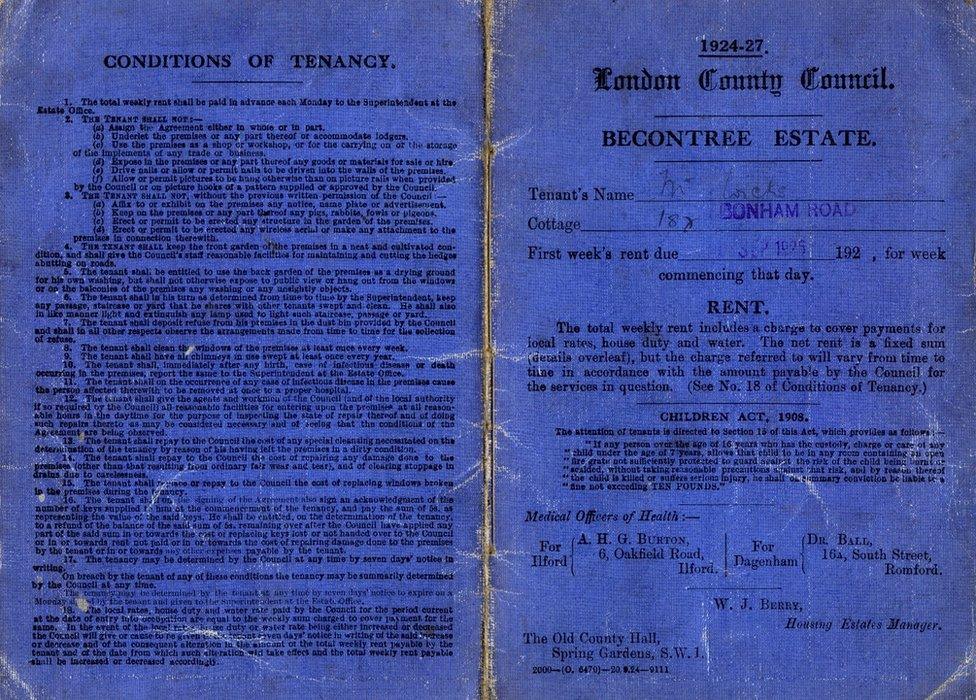

Becontree was the first council house estate to be built under the Addison Act

The estate under construction in 1927 - it would eventually cover four square miles

Smells of grass, freshly grown flowers and the surrounding acres of fields were a stark contrast to the toxic smog in the city.

"It was just like being in the countryside - the air was so fresh, despite some construction work still taking place," says Peter. "You could even go pea and potato picking in the fields nearby. Becontree was simply a working class haven."

The 96-year-old still lives on the estate in Burnside Road - two streets away from his childhood home - and is one of the few who still remember what it was like in its early years.

He recalls how London County Council attempted to discourage heavy drinking by refusing to build no more than six pubs on the estate and how residents had to adhere to strict rules. Parents had to ensure their children were kept orderly, no washing could be hung from windows and front gardens had to be kept neat.

"My father, who worked in a biscuit factory in Bermondsey, used to complain there wasn't a pub on the corner [at home] where he could enjoy a few pints after his long commute. Some families moved out of the area for that very reason."

The Becontree tenants’ handbook contained 20 conditions, ranging from parental responsibility for the “orderly conduct” of children to requiring that no washing was hung from windows

At the time Peter and his family moved in, Becontree was proclaimed the world's largest council estate, with 26,000 homes. The four square mile estate, which was finally completed in 1935, is still considered to be the largest in the UK, followed by the Wythenshawe estate in Manchester.

"Becontree was among the first of the London County Council's post-war schemes in 1919," says social housing author, John Boughton.

"It was certainly the largest in the UK when planned and developed in the interwar period. In terms of population, it's probably since been superseded by some large estates in the former Soviet Bloc but it must remain one of the largest in area today."

Barry Watson lives with his wife, Shirley, in one of the estate's desirable "suntrap houses" on Wykeham Avenue. She grew up 10 minutes away, on the same estate, in a two-bed home that belonged to her parents, who moved from Hackney when their house was bombed in the Blitz.

Around the same time, Barry moved in with his grandparents, who had moved from Poplar to Hunters Hall Road in Becontree in the 1940s.

"One abiding memory of my childhood was my grandmother's fear of the 'terrifying weasel-looking' rent collector," says Barry, 77. "He would report people if they didn't keep their hedges trimmed or if their curtains were not clean enough."

The gardens were a source of pride for many

As revenge for confiscating a football, Barry and his friend once played a "cruel trick" on the rent collector.

"We put a piece of chewing gum which was hiding a drawing pin on the latch of his gate. On top of that piece of chewing gum was some cat poo - and I bet you can imagine what happened," he said mimicking someone sucking their thumb in pain.

"A month or so later, he fell off his bike in the street and not one person went over to help him. That's how universally hated he was."

'Homes for Heroes'

Crowds flocked to the opening ceremony of Becontree in the 1920s

Housing became a national responsibility in July 1919

The Addison Act tasked local authorities with developing new - and equipped - housing for working people

Chancellor David Lloyd George hoped his "Homes for Heroes" project would improve the health and stability of the nation by providing good quality housing for families of those returning from war

30,000 of those were planned for London, while 24,000 of them were to be built on garden land in Dagenham, Ilford and Barking due to the lack of available space in the county of London

It was designed as a cottage garden estate, where parks, gardens and green spaces were as important as houses. Each property would have front and back gardens, hot and cold water, one or two living rooms, a scullery and indoor bathrooms and toilets

By 1921, 4,000 houses had been completed and the first tenants moved into Becontree at the end of that year. Between 1924 and 1930 a further 15,000 houses were built, followed by 7,736 more by 1935

Today, there are more than 27,000 houses on the estate

The estate, which was finally completed in 1935, is still considered to be the largest in Europe

The Becontree estate was a groundbreaking scheme that re-housed some 100,000 people, many of whom had lived in London's slums.

The allure of a spacious home with running water, two to four bedrooms and a parlour was hugely appealing, despite conditions that windows were to be cleaned once a week, doorsteps must be scrubbed and children were banned from playing in communal gardens. If families failed to meet these standards, they faced being thrown out of their homes.

It was a novel idea and one that attracted attention from royalty to famous people who took up residence, including singer Sandie Shaw, England football manager Sir Alf Ramsey and footballer Bobby Moore.

"It was such an innovative scheme that King George V visited the estate in 1923, when he had tea with one of the early tenants," remembers Bill Jennings, who moved to the estate in 1954.

"Mahatma Ghandi once spent the night at Kingsley Hall [community centre], leaving a portrait of himself and a spinning wheel as gifts to the community."

Windows were to be cleaned once a week, doorsteps must be scrubbed and children were banned from playing in communal gardens

But all was not rosy. Becontree was often referred to as "Corned Beef City" by historians and commentators because of the "staple diet" of its "poor residents".

Alexander McDonald, who lived on the estate from 1921 until he was 81, wrote in his memoirs that he had never heard it referred to by that name.

"I agree that there were some very poor people [living there] but there were many more men who had jobs to go to."

But he conceded that the estate was unfinished when he moved from Poplar to 5 Manor Square when he was five years old and how the property had no fences and no garden, as it was still "littered with builders' equipment".

"Some of Becontree was but a muddy lane with a ditch running its length and filled with water. We used to watch the water voles swimming about in them," he wrote.

Many of the homes, once identical, now have character

Barry Watson has lived in one of the estate's "suntrap houses" on Wykeham Avenue since the 1940s

Alexander's daughter Christina said while her father's memories of the estate were mostly happy ones, he had considered it a "dump" in the years before his death.

"Throughout my father's life he watched the estate decline steadily," she said. "The budgets for parks and gardens and general maintenance must have felt a serious squeeze and everything generally felt much less cared for.

"Front gardens have become driveways and flower beds are now a place to put rubbish bins. One has to wonder what the next hundred years will see."

Alexander McDonald's family moved to 5 Manor Square in 1921

You might also be interested in:

Walking through the estate today, dozens of cars line pavements, wheelie bins rest against the front of garden walls, and satellite dishes are dotted on roofs. Its near-identical streets, whose houses once all looked the same, now have a sense of ownership about them: one house is painted pink, another is coated in trails of wisteria.

"The estate has changed vastly throughout the years," says Peter. "People used to fight over who had the best kept garden, now they are merely extra space for cars or rubbish.

"But that's life. You can't change it. All I have is the lovely memories of my beautiful home and how Becontree became Becontree."

- Published7 July 2019

- Published21 June 2019

- Published19 May 2015

- Published14 April 2015