Liberia - the country where citizenship depends on your skin colour

- Published

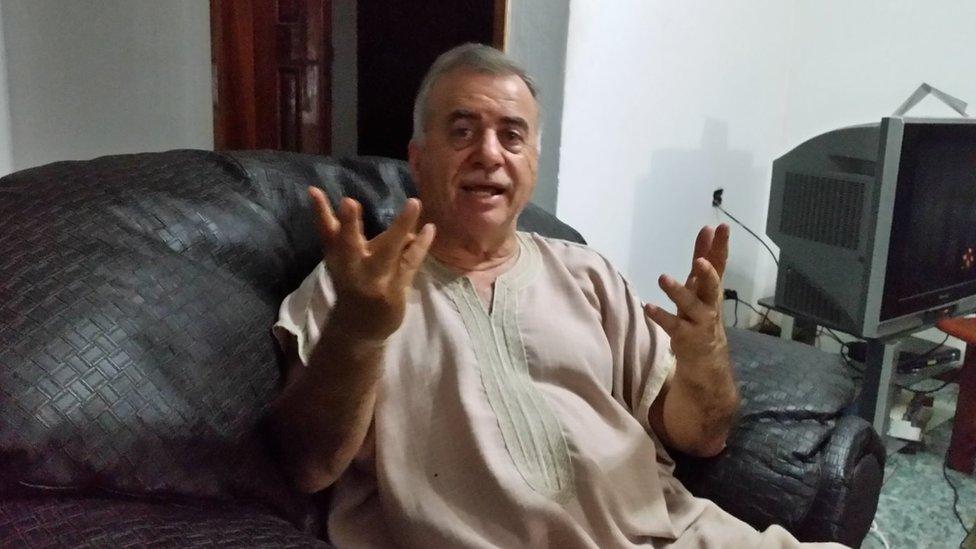

Tony Hage has lived in Liberia for more than 50 years.

It is where he went to university. Where he met his wife. Where he set up his successful business.

He has stayed when so many others have fled the country's years of unrest- determined to see the country he loves and calls home succeed.

But Mr Hage, it could be argued, is a second-class citizen in Liberia. In fact, he is not a citizen at all - prohibited from becoming a full member of Liberian society because of the colour of his skin and his family's roots in Lebanon.

'They will enslave us'

Liberia, on Africa's west coast, was established as a home for freed slaves returning to the continent, escaping from unthinkable misery in the United States.

Perhaps, then, it is unsurprising that when the constitution was created, a clause was put in restricting citizenship to just those of African descent, creating "a refuge and a haven for freed men of colour".

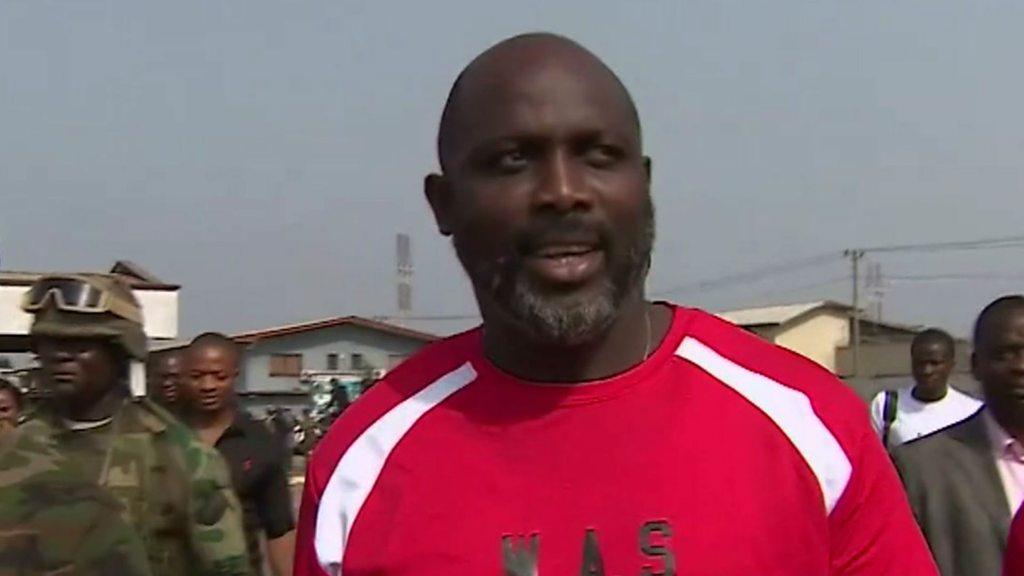

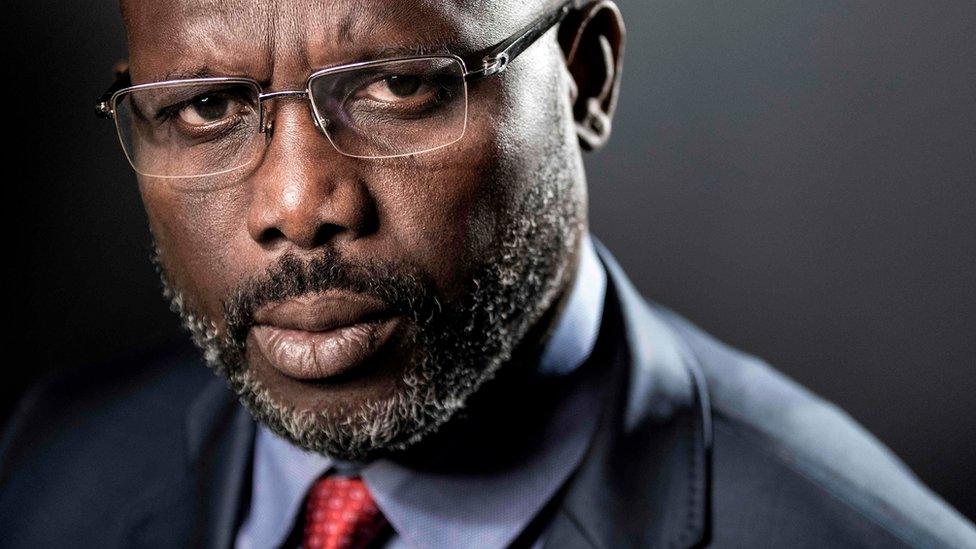

Hundreds of years later, Liberia's new president, the former footballer George Weah, described the rule as "unnecessary, racist and inappropriate".

What's more, Mr Weah said, discriminating against races "contradicts the very definition of Liberia", which is derived from the Latin word "liber," meaning "free".

The pronouncement has sent shockwaves through some parts of Liberia.

"White people will definitely enslave black Liberians," businessman Rufus Oulagbo tells the BBC, bluntly.

Fubbi Henries at a protest against dropping the colour provision of the constitution

He fears any move to widen citizenship away from just black people would damage Liberians' chances to develop their own country.

In particular, he says, allowing people from other countries to own property would be dangerous.

Mr Oulagbo is not the only one to voice these fears: a new advocacy group, Citizen's Action Against Non-Negro Citizenship and Land Ownership, has been set up to fight the president's plans.

"Every nation has a foundation on which it was built - if you undermine that foundation, the nation will definitely crumble," the group's leader Fubbi Henries told the BBC.

Mr Weah, he said, "needs to focus on the right policies for Liberians".

"Right now the prime focus is how to get our businesses on track, our agricultural and educational sectors on track, not citizenship or land ownership to non-Negroes," he said.

It is true Mr Weah has his work cut out without changing the constitution.

Despite its wealth of natural resources, Liberia is ranked 225 out of 228 countries when it comes to average income per person, at just $900 per year for 2017.

In comparison, the US figure was $59,500, while the UK's was $43,600.

In fact, a third of Liberia's GDP comes from those living overseas - with some families entirely dependent on remittances from the US.

Mr Weah has been blunt in his assessment of the situation: Liberia is broke, and he is going to fix it.

How is Africa's most beloved footballer going to turn Liberia's economy around?

After years of civil war - not to mention the devastating effect of the Ebola epidemic in 2014 - the promises are music to most Liberian ears.

But changing the law now, Mr Henries says, would be like putting a two-year-old boy - Liberians - and a 45-year-old man - outsiders - in a boxing ring and seeing if they could have a fair fight.

"He will take undue advantage over that little child," he said. "Liberian businesses don't have that same leverage."

Harmony

The fear of outsiders is nothing new. The Lebanese community is used to it.

"Probably some people might take this as a threat - that foreigners are coming to take over," Mr Hage tells the BBC from his home in Monrovia. "That's not the case."

At its height in the 1970s, Liberia's Lebanese community was 17,000-strong. Now, after Liberia's long civil war, it numbers around 3,000 - barely a drop in the ocean in a population of four million.

At one point, Lebanese families had businesses across the country. Even now, the community owns some of the country's top hotels and businesses.

But, says Mr Hage, that should never worry their Liberian-born neighbours.

"Lebanese were all over in this country and it wasn't any threat; and we have enjoyed living with Liberian people," he said.

"Liberian people are fine people; and we have lived together for all these years, we have had inter-marriages. The records speak for Lebanese in this country."

Tony Hage has lived in Liberia for most of his life

In fact, he believes that should Mr Weah's proposal go forward, it would open the way for even more cooperation.

But on a personal note, it would mean a huge amount to him.

"I have always hoped that one day the clause would be changed.

"I celebrated my 15th birthday in Liberia, I have never regretted living in Liberia.

"I am happy not because I am not a Liberian, I am happy because President Weah is looking at the future of this country,"

- Published23 February 2018

- Published12 February 2018

- Published22 January 2018

- Published13 February 2024