Japan's military revolution hints at Shinzo Abe's nationalist aims

- Published

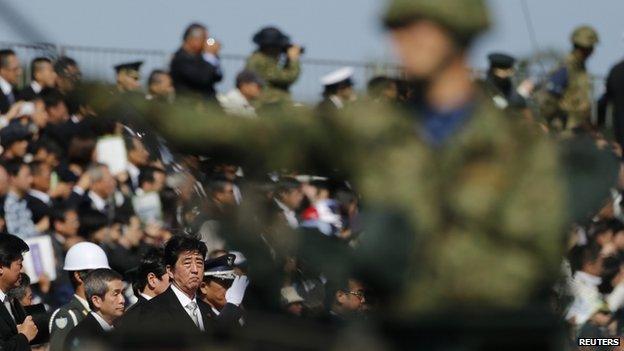

PM Shinzo Abe has called for Japan to broaden the scope of activities performed by the military

Japan has announced a plan to increase defence spending and transform its military, in a move widely seen as aimed at China. But many on the left believe Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is using the threat from China to pursue his own nationalist dreams, reports the BBC's Rupert Wingfield-Hayes in Tokyo.

For a country that, according to its constitution, does not maintain any army, navy or air force, Japan spends an awful lot of money on defence.

This year, it was about $60bn (£37bn, 44bn euros) or roughly the same as the UK or France.

Of course, Japan does have a military - a large and modern one. But it was designed in the days of the Cold War to protect Japan against an invasion from the north, from Russia.

'Stand up to China'

But over the last 10 years, China has transformed its military at an astonishing rate. Beijing's defence budget has more than doubled to over $150bn a year.

Today, China is launching new navy ships faster than any other country in the world. It is developing stealth fighter jets and drones, and of course it now has its own aircraft carrier.

Then last year a long simmering dispute over a tiny group of islands in the East China Sea, that most people had never heard of, suddenly burst on to the front pages.

Japanese governments have long talked of the need to "stand up to China". Little has come of it.

But last December, Japan elected as prime minister an avowed nationalist, Shinzo Abe, who promised he would not be pushed around by Beijing anymore.

And so here we are, a year later, with Mr Abe's new defence strategy. Its aim is to address the threat from China head on. And the threat is first and foremost to those islands in the East China Sea.

Shopping list

And so Japan will create a new amphibious assault force, effectively a marine corps.

Japan is not allowed offensive military forces under its post-war constitution

There is a big shopping list too. Twenty-eight F-35 stealth fighters, 17 Osprey tilt rotor aircraft, 52 amphibious assault vehicles, 99 light combat vehicles.

Japan is already building two large helicopter assault carriers. Together these will form the core of Japan's new amphibious forces.

So what, you may ask. Any responsible government needs to plan its defence policy based on present and future threats. From that point of view, what Mr Abe is doing is only sensible and responsible.

However, there are many in Japan who suspect Mr Abe of having another agenda.

Suspicious

Shinzo Abe is at heart a right-wing nationalist. Throughout his political career, he has called for the overturning of Japan's post-war pacifist constitution.

Mr Abe has also shown a deep ambivalence about facing up to Japan's crimes against Korean and Chinese people during World War Two.

In the past, he has denied that the Japanese military was involved in the coercion of hundreds of thousands of Korean and Chinese women to work as prostitutes in military brothels.

He has openly questioned whether Japan should be defined as an "aggressor", and he has campaigned for the revision of school history books to give a more positive view of Japan's war-time role.

But for Mr Abe and his supporters, the barrier to changing Japan's peace constitution is extremely high.

People protest against the government's State Secrets Act in Tokyo

He must get two-thirds of the votes in both houses of parliament and win a referendum.

No-one thinks he can do it. And so Mr Abe's critics, and there are many, say he is trying to change Japan without changing the constitution.

Last week, he centralised all military decision-making in a new US-style National Security Council that comes directly under the prime minister's office.

His party pushed through a tough new secrecy law that will greatly widen the number of things that can be classified as a "state secret" and make the penalties for leaking them much more severe.

Thousands of Japanese protested outside parliament all week long as fierce rows shook the chamber inside. I asked some of those braving the cold why they were so opposed to the new secrecy law.

"Because Abe wants to take us to war," many said.

It struck me as a strange response to a secrecy law that is little different from those already in place in the UK and US.

But Japanese liberals are extremely suspicious of the old Japanese right.

They believe deep down that people like Mr Abe really want to take Japan back to the pre-war era, when the emperor was a god and obedience to the Chrysanthemum Throne came above all else.

- Published17 December 2013

- Published23 October 2017

- Published17 December 2013

- Published28 November 2013

- Published26 November 2013

- Published4 December 2013

- Published10 November 2014

- Published22 November 2013