India election 2019: Is the switch to gas in the kitchen working?

- Published

The Indian government launched a flagship scheme in 2016 to eliminate the indoor pollution generated by using kerosene, wood and cow dung on cooking stoves by encouraging the use of cleaner fuel.

This scheme involved supplying of bottled cooking gas to tens of millions of rural households across the country.

In the run-up to the Indian election, which gets under way on 11 April, BBC Reality Check is examining claims and pledges made by the main political parties.

Claim: The Indian government says the gas scheme is significantly reducing the use of more polluting household fuels - but the opposition Congress Party says it is "half-baked and structurally flawed".

Verdict: The scheme has led to a big increase in households using liquid petroleum gas (LPG) - but the cost of having cylinders refilled is reducing its initial successes.

The scheme initially targeted households below the official poverty line, in rural areas.

Then, in December 2018, the government announced it was being extended to poor households across the country.

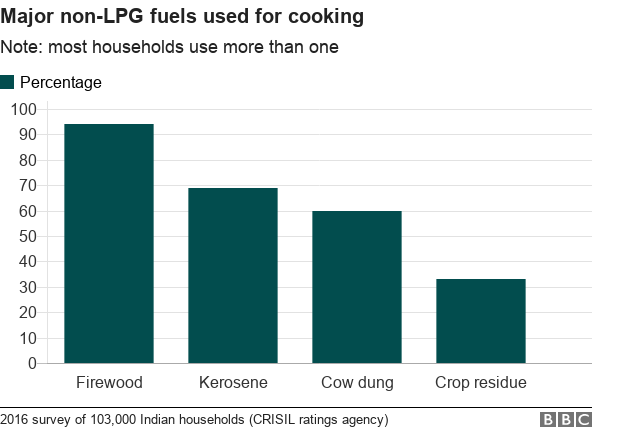

Before the project was launched in 2016, most rural households in India cooked with a variety of high-polluting, locally available fuels.

The BJP government says the shift to LPG has been a great success and most of those benefiting are women.

The opposition Congress party says more than 100 million Indians are still using kerosene oil and other fuels for cooking instead of the cleaner LPG.

The government scheme pays gas suppliers for every free LPG connection they install in households.

And each connected household can buy its first LPG cylinder using an interest-free government loan.

However, they have to pay for all subsequent gas cylinders themselves, albeit at a subsidised price.

The scheme is designed to encourage cleaner methods of cooking

When the BJP government came to power, in May 2014, 130 million LPG connections had already been made in India, under schemes launched by previous governments.

By 9 January 2019, the last date for which figures are available, almost 64 million new LPG connections for poorer families had been completed.

So it's possible the government might meet its own target, of 80 million by May 2019.

But this is not the whole story.

Read more from Reality Check

What's happening with refills?

Since the scheme was introduced in 2016 the cost of unsubsidised LPG gas cylinders has risen considerably.

The government has sought to reduce the impact of the rise by increasing the subsidy offered.

But this subsidy applies only to the first 12 cylinders purchased - after that the gas must be bought at the full cost.

And some recipients have complained that the subsidy can only be claimed after having purchased the gas at the full price, which can be hard for poorer families to do.

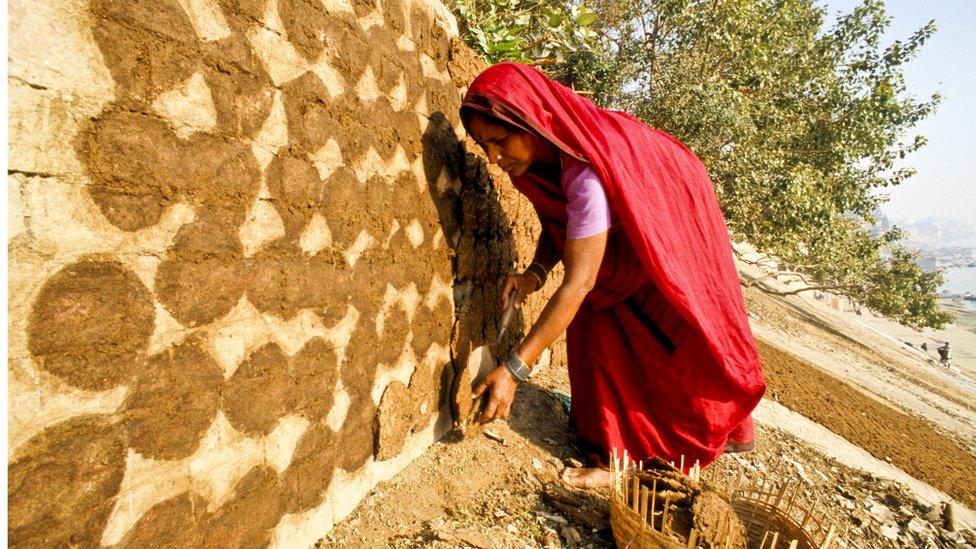

Dried cow dung is used as a fuel in rural areas

Journalist Nitin Sethi filed Freedom of Information requests with the government to find out the numbers of families buying refills after the initial LPG connection.

"It was clear that a majority of those families who have been given LPG connections for free do not get them refilled for the second time because they can't afford it," he says.

He says they then revert back to traditional methods of cooking, with cow dung cakes and firewood.

But this is not the government's view.

Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan says 80% of those provided with new LPG connections have already bought at least four refills.

The cost of buying gas refills has put many households off the scheme

He adds: "20% of those who are not getting their cylinders refilled do not do so because they live near forest areas where they have easy access to firewood."

Of the households that remain unconnected, 35% have access to free fuel - more than a third use firewood and the rest cow dung, external - according to financial analytics agency Crisil.

It says the lengthy wait to refill cylinders - as well as the cost - also puts people off.