Nasa's Perseverance rover is shooting lasers across Mars!

- Published

- comments

Listen to the staccato pips as the laser fires on Mars

Since landing on Mars on 18 February, the rover Perseverance has been collecting data to send back home to study for evidence of past life on the red planet.

And now we can listen to the sound of the lasers is uses to gather data!

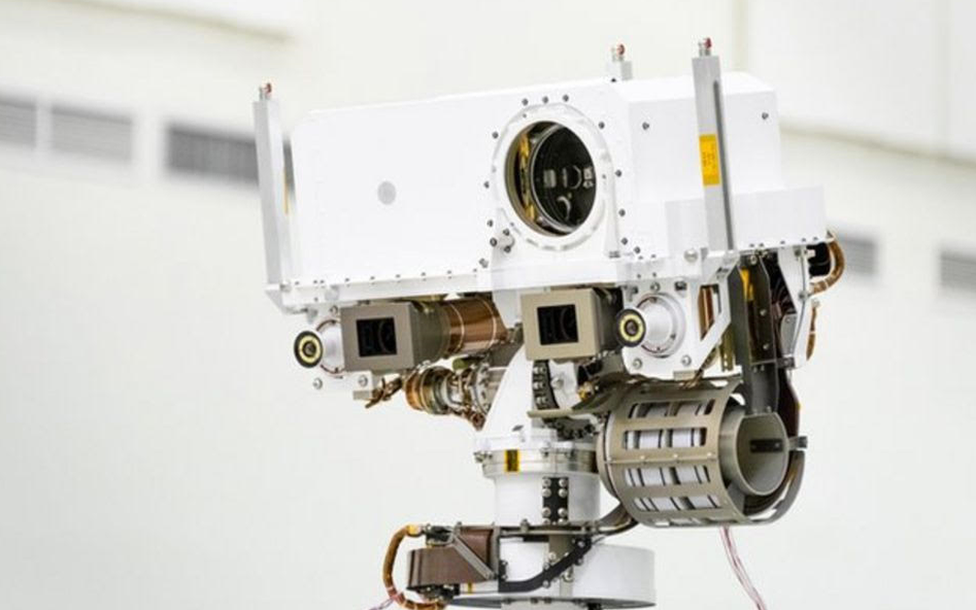

Nasa's little robot has been using its SuperCam instrument for the first time, where it uses lasers to detect rocks and send information about those rocks back to scientists on Earth.

Scientists can use the sound of the lasers to understand how hard the rocks are on Mars - different rocks have different sounds depending on how hard they are.

The lasers used by Perseverance in the video are similar to those used by previous rover Curiosity - except that perseverance has a microphone attached so that we can listen to them.

Perseverance has a function that shoots lasers at rocks built into it, including a microphone so we can listen to it!

How does it work?

The rover is currently roaming the Jezero Crater, a deep bowl on Mars that is hoped to be the best location to find evidence of some sort of life.

If we tap on a surface that is hard, we will not hear the same sound as when we fire on a surface that is soft.

This is because scientists believe that the crater most likely held a lake there billions of years ago.

The sounds you can hear in the video above are called staccato pops, and these are being bounced off a rock that has been called Máaz - named after the language Native Americans spoken in the south western USA .

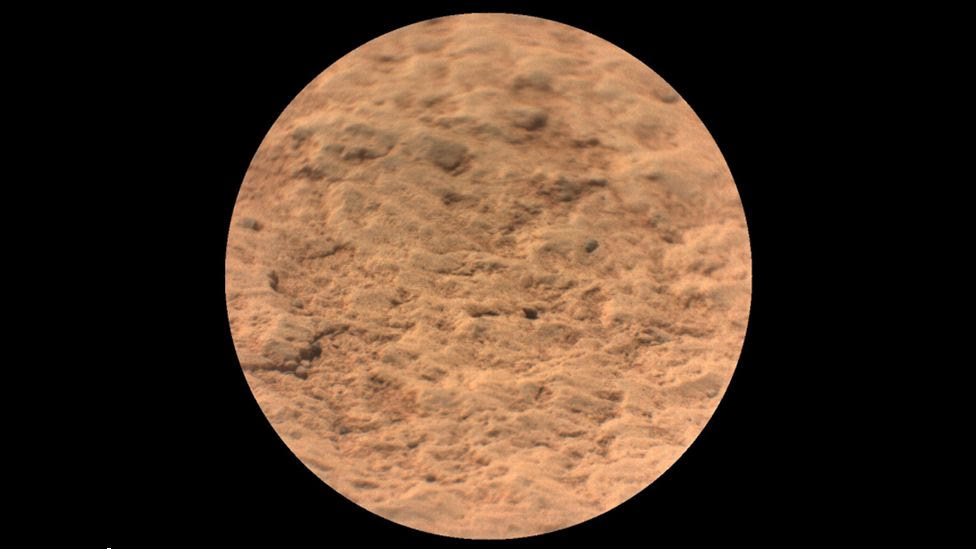

Perseverance sent back an image of the rock on Mars which is called Máaz

What have they found?

The Máaz rock was found to be basaltic - this is a word used to describe rock that has formed from the cooling of lava.

Scientists don't know if the rock is volcanic or not, but the discovery is helping them understand Mars' surface.

Roger Wiens, from Los Alamos National Laboratory said: "We'll have to use more of our techniques and study the surrounding area to understand those details some more."

- Published11 March 2021

- Published11 March 2021

- Published11 March 2021