Benefits spending: Five charts on the UK's £100bn bill

- Published

Paying benefits to people of working age is a big part of what the government does.

In fact, it spends more on these benefits than it does on education or national defence and policing.

They account for roughly £1 in every £8 the government spends, or about £100bn a year. This is on top of the £120bn that is spent on benefits for pensioners.

A look at the size of the bill and who gets these benefits reveals big changes over time.

Most people will receive benefits

There are about 1.8 million households of working age who get at least 80% of their income from benefits.

But there are two reasons why the system is far wider than this.

First, many more households get smaller income top-ups from it.

About half of all working-age households currently receive some benefits. Even excluding child benefit - which all but the highest-income families are eligible for - the figure is about one in three.

Second, working-age benefits are not simply supporting an unchanging group. Most of us will draw on them at some point, external - for example, during periods of low income, parenthood or ill health.

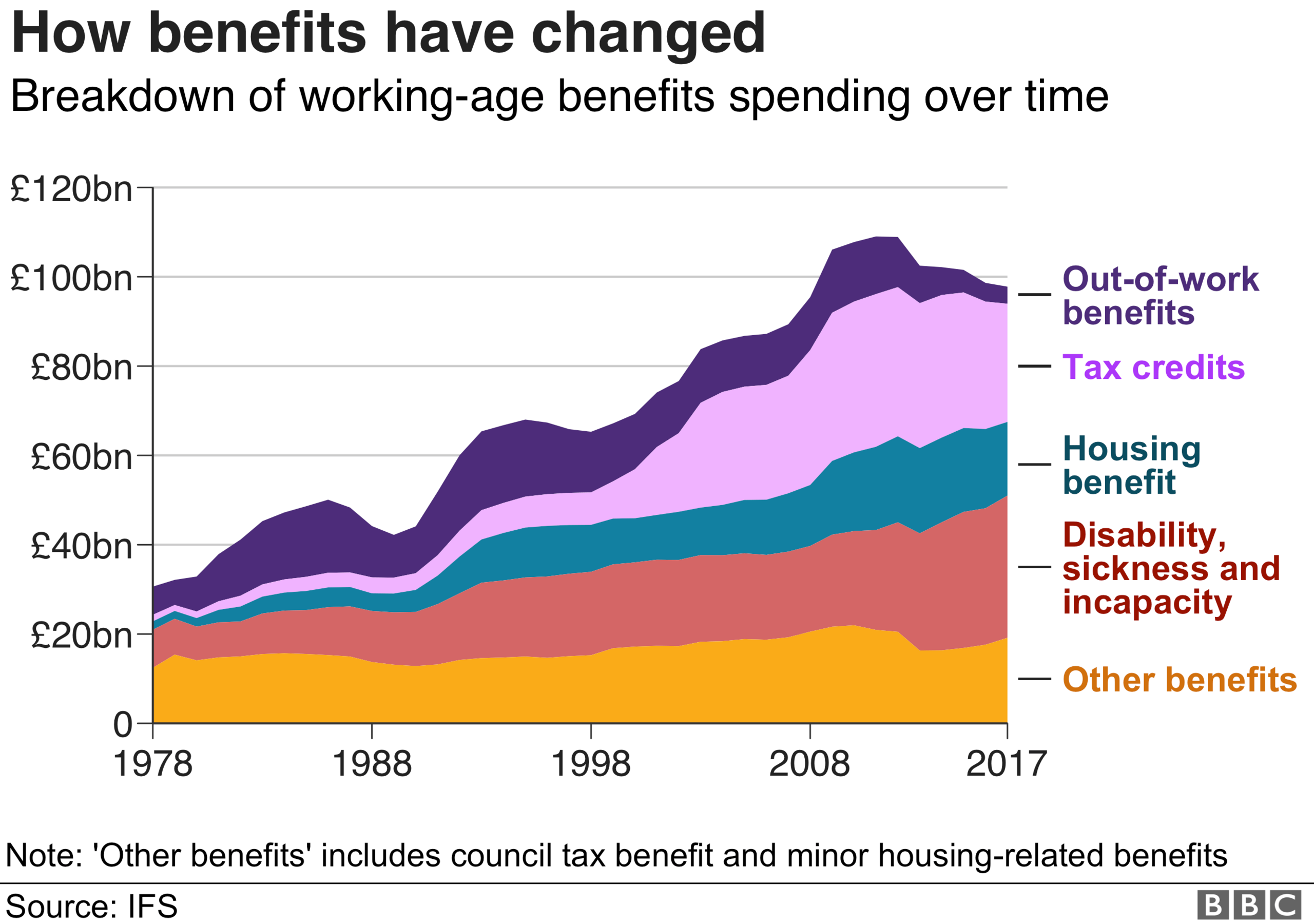

About three-quarters of working-age benefits are spent in one of three ways:

Tax credits, mostly topping up the incomes of families with someone in paid work, but on modest earnings

Housing benefit, helping low-income people meet the cost of rent

Disability, incapacity and sickness benefits, for those whose health limits their ability to work or adds to the cost of living

These benefits now dwarf those designed to support the unemployed, in part because of the rapid fall in unemployment.

This has been accompanied by a shift in the way that we decide who gets support.

The original vision for the welfare state was a largely contributory one. Those who had paid social security contributions when in work were entitled to support later on if they fell on difficult times.

We have since turned increasingly to means-tested support - essentially offering financial help to people if they appear to need it, regardless of past contributions.

Supporting people who are working

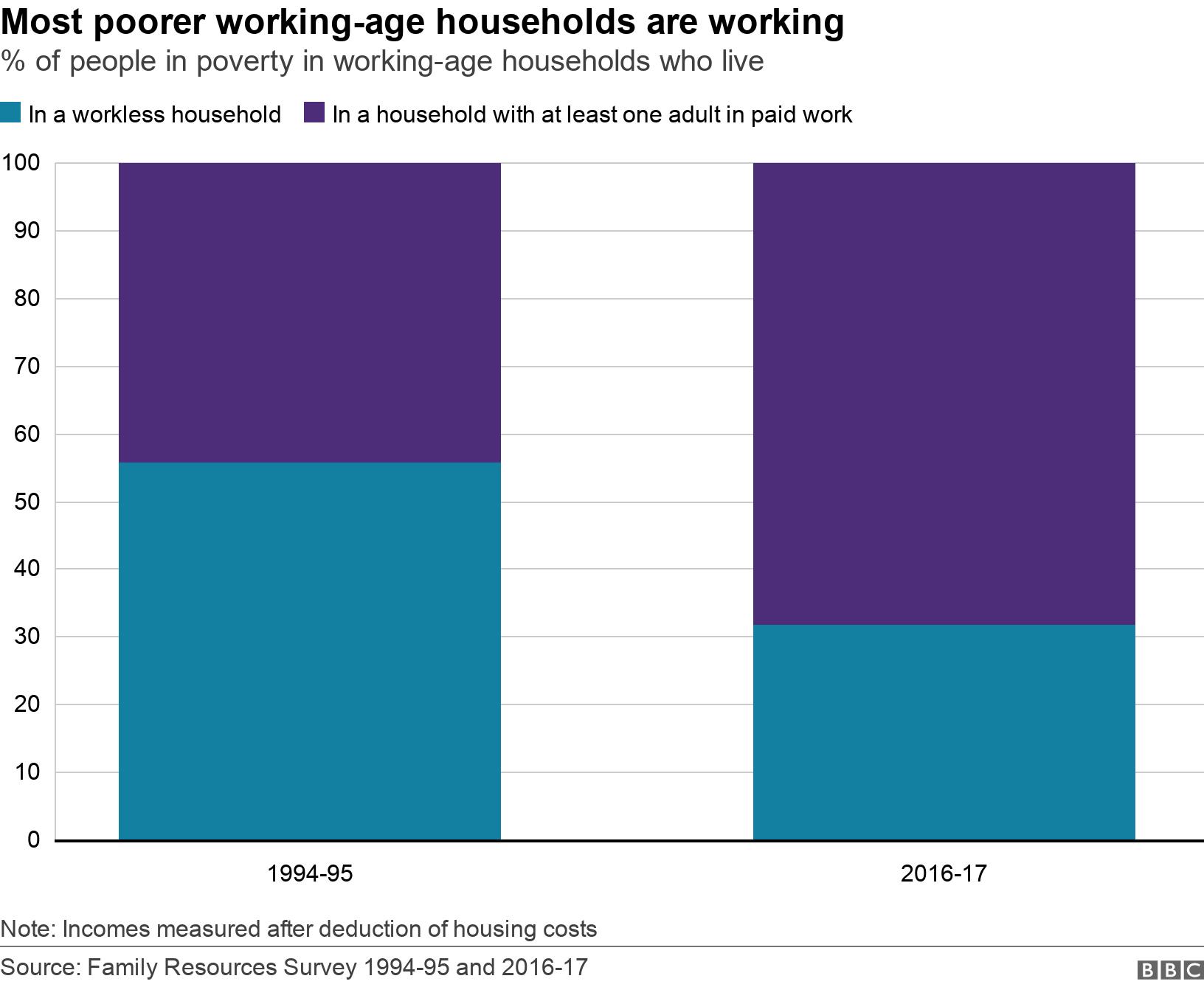

Today, more of the poorer sections of society are in working households than in the past.

Twenty years ago, most non-pensioners whose income was below the official poverty line were in a household where no-one was in paid work.

Now, more than two-thirds of such people are either in work or live with someone who is.

That is the result of both good and bad news.

On the one hand, unemployment is much lower than in the past.

But on the other hand, for those who are in work, pay growth has been very weak. This means that work is a less reliable route out of poverty than we might have expected.

After adjusting for inflation, the lowest-earning working households today earn little more than their counterparts in the mid-1990s, external.

Tax credits in particular are being used to plug the income gap left behind by a lack of pay growth.

In 1994-95, 40% of working age benefits were paid to households with at least someone in paid work. In 2016-17, this was 58%.

Support for housing costs

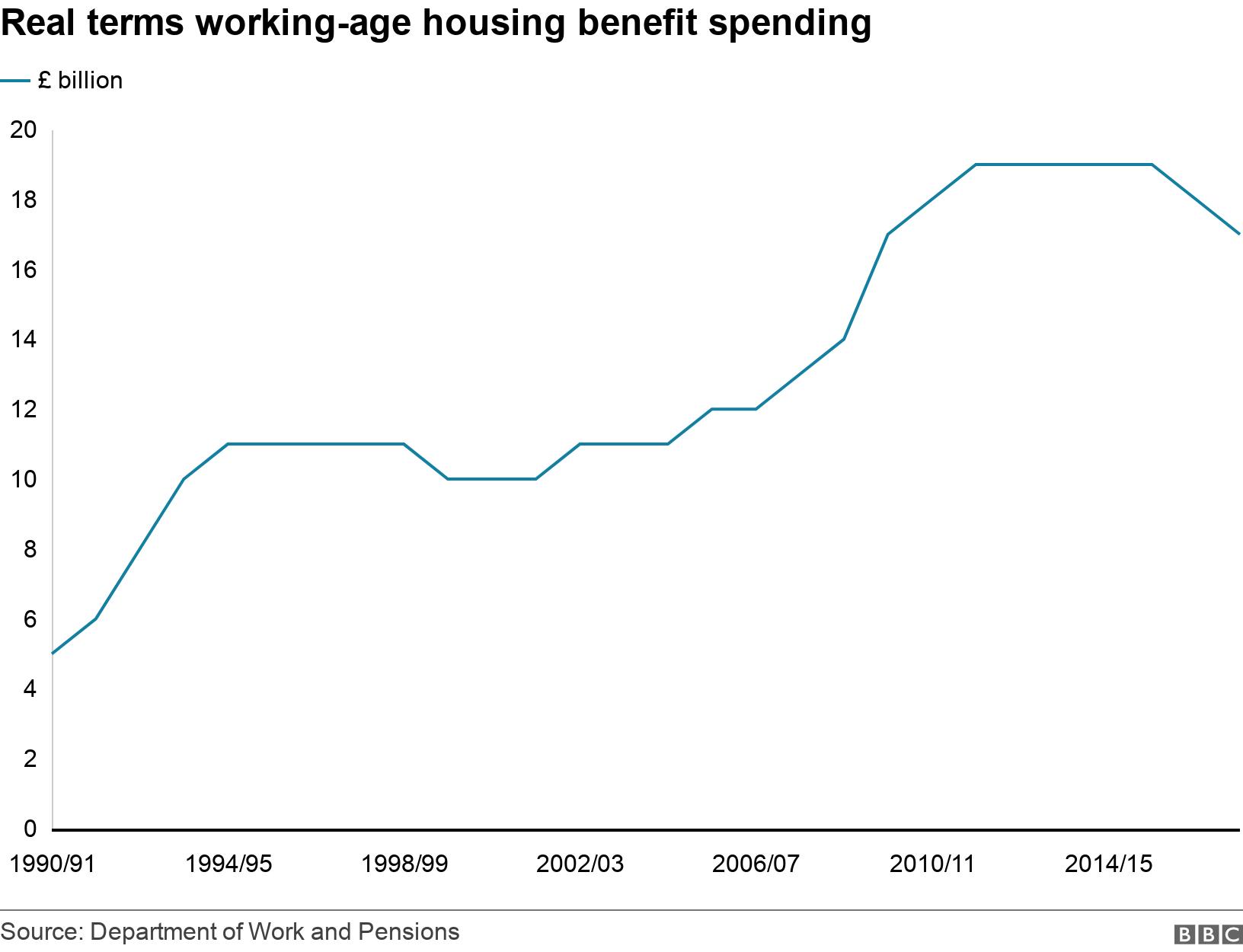

Housing benefit exists to help low-income renters pay for a home.

It costs the government more than policing, overseas aid and various government departments.

Three million working-age households receive £17bn per year in housing benefit, with a further £6bn going to pensioner households.

Spending in this area has roughly doubled since the early 1990s, after adjusting for inflation.

In part, this is because other forms of public support for housing have fallen. For example council housing, in which rents are typically well below market levels, has been in decline.

The proportion of people living in council housing has fallen from about one-third in the 1970s to less than 10%.

And in recent years another large factor has been falling rates of home ownership. This has fuelled massive growth in the size of the private rented sector, where costs are higher.

Growth in the number of people needing support for housing costs creates a dilemma for government.

It faces a choice between picking up ever more of the tab for higher housing costs and allowing low income families to do so.

Recently, it has moved towards the latter approach. Since 2012-13 housing benefits no longer increases each year in line with rents.

Incapacity and disability benefits

Another area which has been under government scrutiny is incapacity and disability benefits.

Incapacity benefits are paid to people out of work if their ill health is considered a limiting factor. Disability benefits can be paid to people in or out of work if a disability adds to the cost of living.

The government recently changed the way it assessed people's health and, as a result, had expected to be making fewer payments.

It was very wrong. The numbers on these benefits have continued to grow. Spending has risen - dramatically in the case of disability benefits.

Despite that, stories abound of claimants finding it difficult to get support.

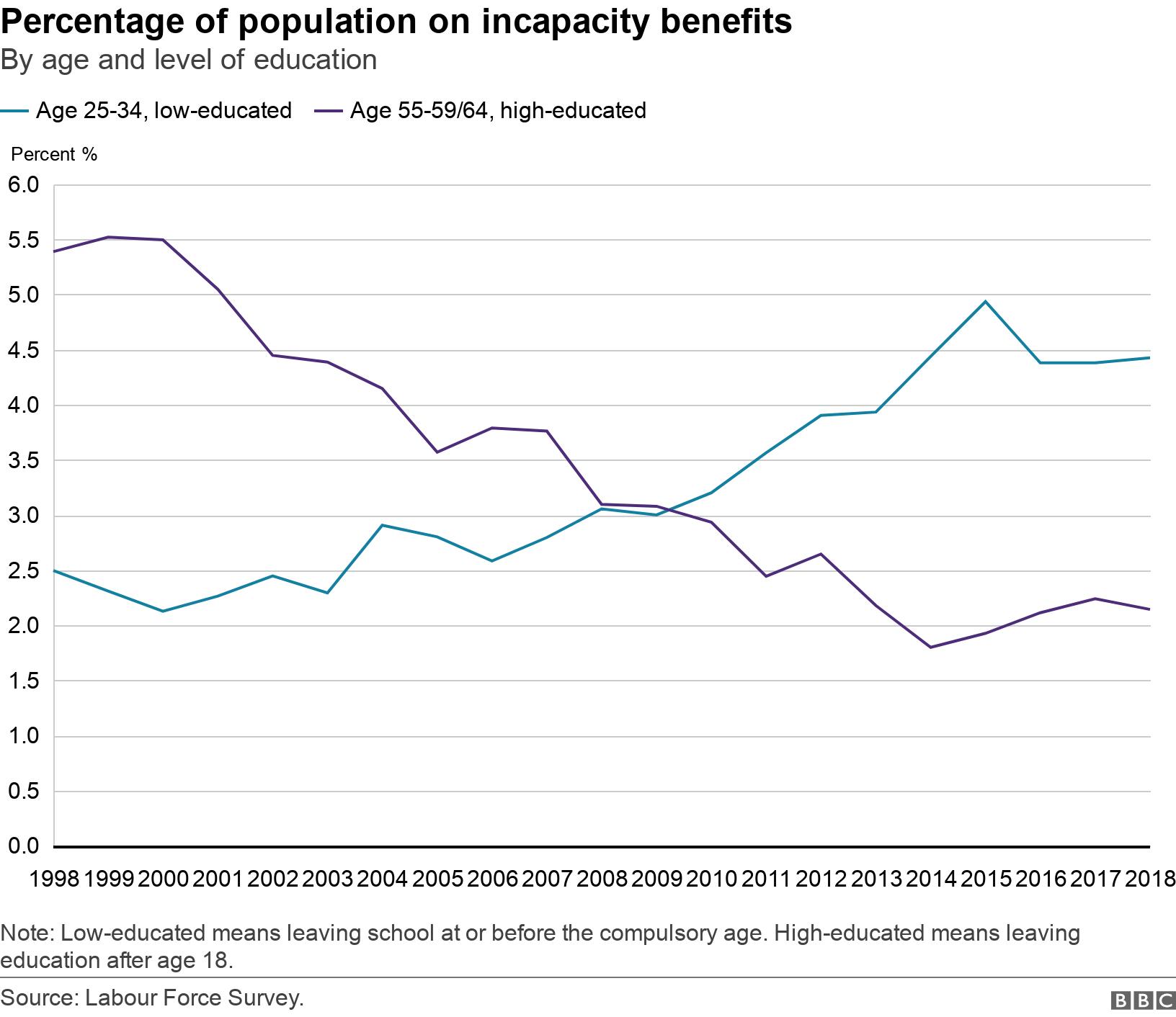

It used to be the case that older age was the best predictor of who would need incapacity benefits. Now it is low education levels.

In other words, these benefits used to largely support people at the end of working life, before they could claim their pensions.

Now they also support large numbers of people in their 20s and 30s. Many have few qualifications, increasing the challenge they face in finding well-paid work.

In addition, the majority of incapacity claimants now have mental or behavioural problems as their primary health problems, rather than physical conditions.

What now?

Benefits are in the midst of an overhaul.

Universal credit - which brings together much of the working-age benefits system into a single payment - is being rolled out across the UK.

But while there are potential advantages of a system that is simpler in this way, it has proved controversial.

Among the reasons are longer waits to receive payments and the intention that universal credit would see overall payments to households reduced.

For all its huge importance, though, it is perhaps easy to focus too much on universal credit.

Much of the £100bn per year we spend on working-age benefits is there to tackle deep problems created by low pay, high housing costs and ill health.

Those are challenges that will remain whatever happens next with universal credit.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Robert Joyce, external is deputy director at the IFS and head of the Income, Work and Welfare sector. In February he presented a talk called The Future of Benefits, external for the 50th anniversary of the IFS.

Edited by Duncan Walker