The retail revolution: How mail order changed middle-class life

- Published

"Beware! Don't patronize Montgomery Ward & Co. They are deadbeats!"

That was the warning issued by the Chicago Tribune on 8 November, 1873.

What had Aaron Montgomery Ward done to convince the Tribune's editorial staff that he was running a "swindling firm" preying on "gulls" and "dupes" in the countryside?

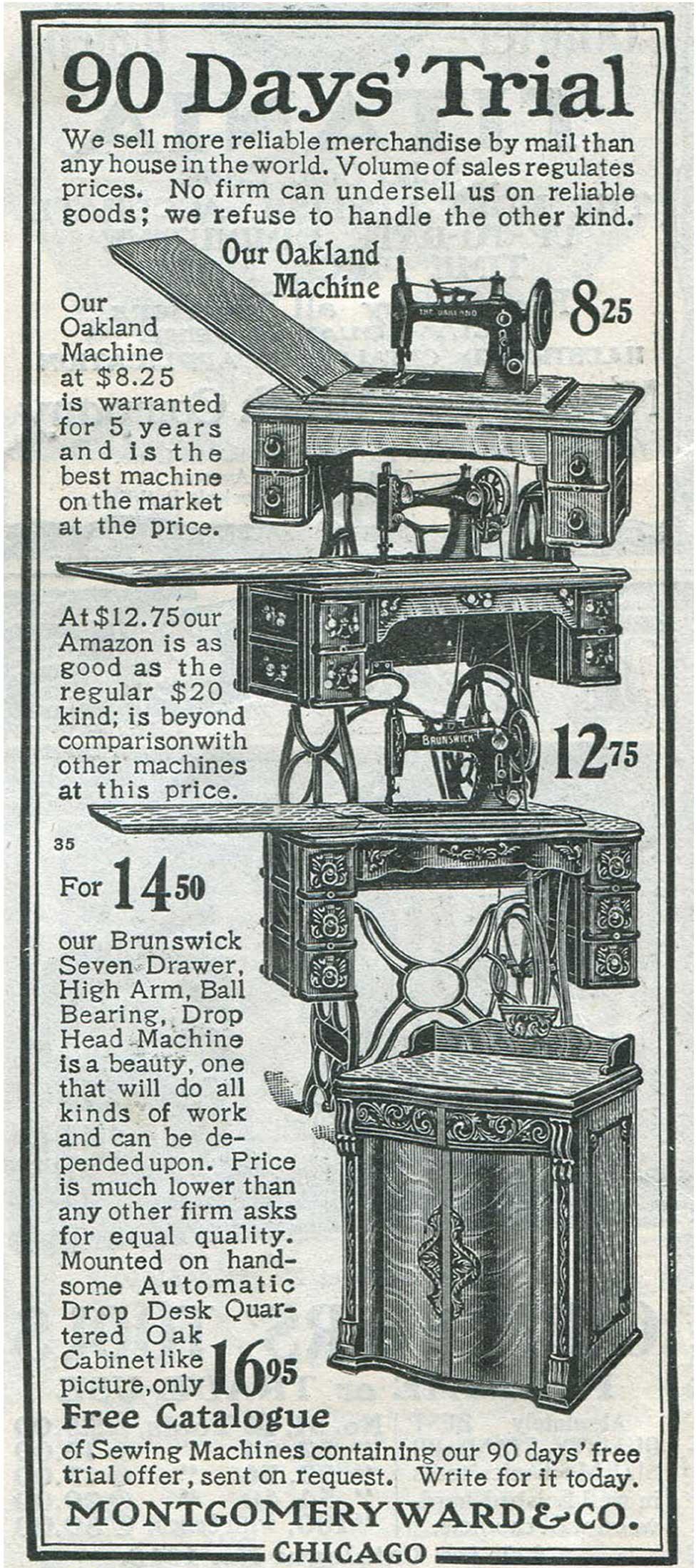

Ward's flyers were offering suspiciously "Utopian" prices on more than 200 goods. And what's more, Montgomery Ward & Co didn't display those wares in a shop, or employ any agents to sell them.

"In fact," the Tribune said, "they keep altogether retired from the public gaze, and are only to be reached through correspondence sent to a certain box in the Post Office."

It seems not to have occurred to the Tribune that Ward might be able to offer his "Utopian" prices precisely because he kept no expensive premises and employed no middlemen.

But the threat of a lawsuit soon helped the editors to wrap their heads around Ward's new business model, and a few weeks later they printed a grovelling apology. Ward put it on his next flyer.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Still in his 20s, Aaron Montgomery Ward had made his way to Chicago after working as a clerk at a country store, and got a job as a salesman for the future department store magnate Marshall Field.

It involved touring more of those rural general stores in farming communities, and Ward realised what a limited selection of goods they stocked, and how expensive they were.

The farmers had noticed that, too. They were already exploring other ways to get goods more cheaply to their far-flung rural outposts.

Mail order existed, but it wasn't common - just a few specialist firms with a limited line of wares.

The opening Ward saw was ambitious but simple: use mail order to sell many things, directly, with low mark-ups on wholesale prices. And let buyers pay on delivery - so if they didn't like what was delivered, they could refuse to pay and send it back.

A chastened Chicago Tribune finally got it: "It is difficult to see how any person can be swindled or imposed upon by business thus transacted."

Ward later gave the world the enduring phrase "satisfaction guaranteed or your money back".

Just two years after rousing the Tribune's suspicions, Ward's flyer had become a 72-page catalogue, listing nigh on 2,000 items.

For 55 cents for example, you could buy 250 5in canary-coloured envelopes or twelve dozen small kerosene wicks. For $6.50, you could treat yourself to an extra fine large white woollen blanket. Ward printed testimonials from satisfied customers, some mentioning that he'd undercut their local store by half.

Despite being basically just a list of goods and prices, Ward's catalogue was later named by New York literary society, the Grolier Club, as one of the 100 most influential books published in America before 1900, up there with Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin and The Whole Booke of Psalmes.

It was, the society said, "perhaps the greatest single influence in increasing the standard of American middle-class living".

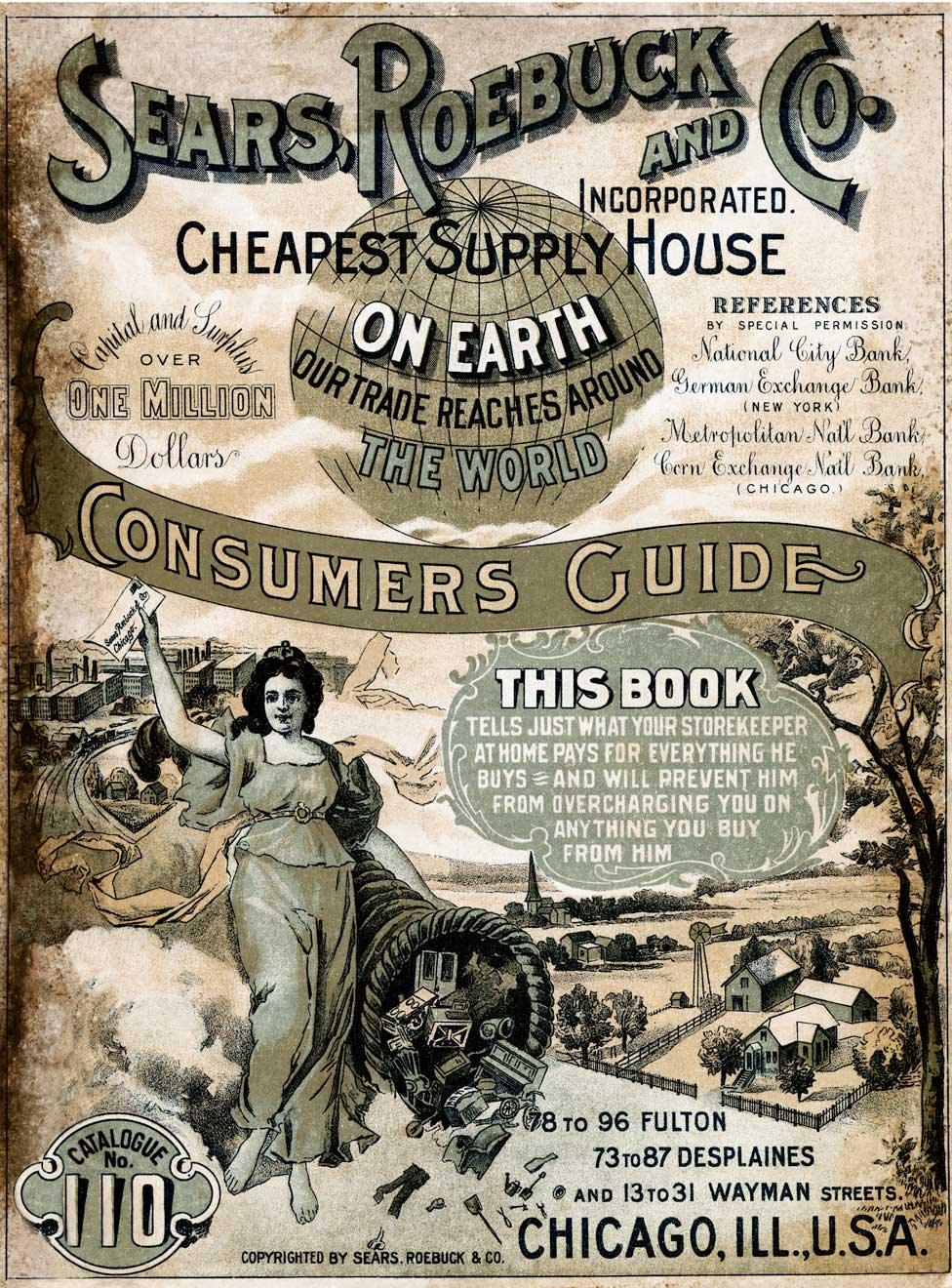

And it inspired competitors - notably Sears Roebuck, which soon became the market leader.

The Sears Roebuck catalogue had slightly smaller pages than Montgomery Ward's, because - it was said - a tidy-minded housewife would naturally stack the two with the Sears catalogue on top.

By the end of the 19th Century, mail order companies were bringing in $30m a year - a billion-dollar business in today's terms.

In the next 20 years, that figure grew almost twenty-fold.

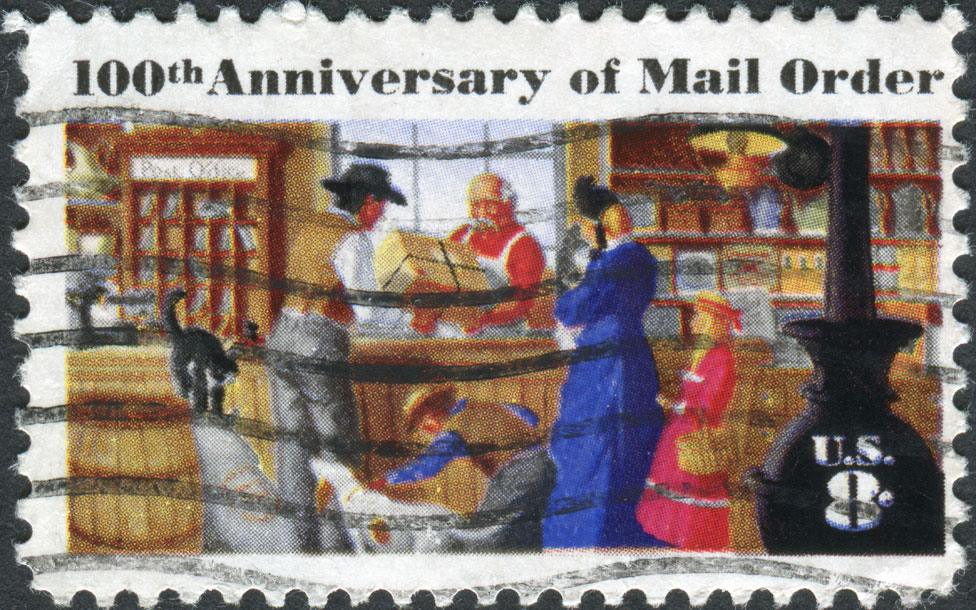

The popularity of mail order helped fuel demands to improve the postal service in the countryside. If you lived in a city, you'd get letters delivered to your door, but rural dwellers had to schlep to their nearest post office.

The government gave in - and realised that if it was going to send postal workers into the boondocks, it'd better improve the road network, too.

"Rural free delivery" was a huge success, and Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck were among the main beneficiaries.

This was the golden age of mail order. Catalogues ballooned to 1,000 lavishly illustrated pages, and new editions were eagerly awaited.

Forget canary-coloured envelopes - for $892, Sears Roebuck would send you a five-room bungalow.

Strictly speaking, you'd be sent "Lumber, Lath, Shingles, Mill Work, Flooring, Ceiling, Finishing Lumber, Building Paper, Pipe, Gutter, Sash Weights, Hardware and Painting Material". And plans of course, which were presumably rather more daunting than the ones you get from Ikea for a Billy Bookcase.

Many of these mail order kit houses are still standing, 100 years on. Some have changed hands for more than $1m.

The catalogue itself has endured less well.

Montgomery Ward and Sears both started building department stores - as wider car ownership made mall shopping more popular, the catalogues became irrelevant.

Montgomery Ward nixed the catalogue in 1985, Sears a few years later.

Then came the internet: Amazon doesn't feel the need to send you a 1,000-page catalogue every year either.

More things that made the modern economy:

But if the heyday of the mail order catalogue has long since passed, its dynamics are now playing out in one country all over again.

The world's rising economic power. A government building roads and communications infrastructure in isolated rural areas. Customers fed up with existing retail options. Visionary entrepreneurs with new business models that let you browse and order from home.

The country is China.

For the postal service, read the internet. And the roles of the mail order giants are being played by China's e-commerce titans: JD.com and Alibaba.

China has thrown itself into online shopping - its citizens spend about as much online as those of the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan… combined.

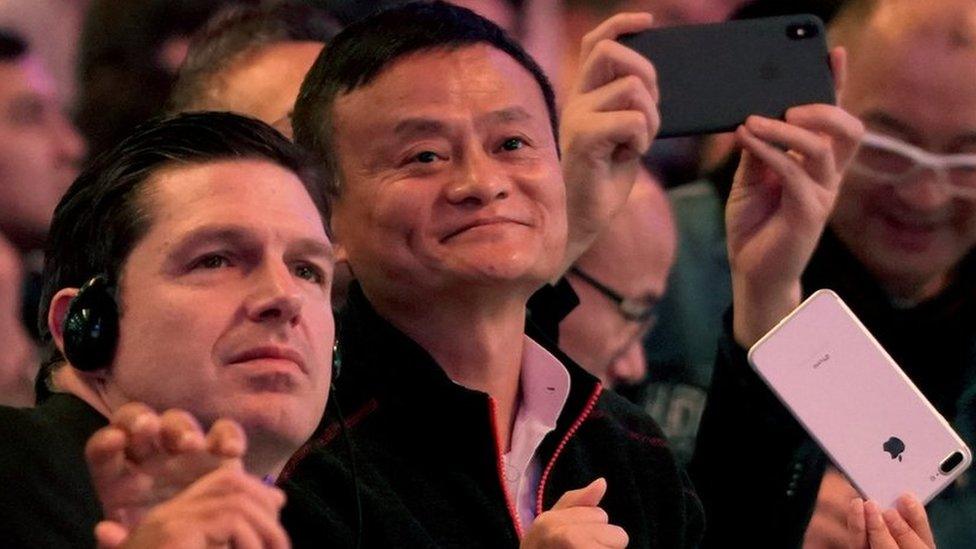

Mariah Carey performed as part of Alibaba's high profile 2018 Singles Day shopping event

Last November, Alibaba set new records on Singles Day, its biggest annual shopping event, hitting $1bn (£774m) in sales in just 85 seconds, and almost $10bn in the first hour of the promotion.

Singles Day is now the world's biggest online sales event, eclipsing Black Friday and Cyber Monday's totals combined.

But drawing rural areas into the economy isn't just about expanding consumer choice and middle-class living standards: when you have good roads and access to information, you have more scope to make and sell stuff.

Two economists studied how rural free delivery rolled out in America, external, and found that when it arrived in a new county, investment in manufacturing soon followed.

The same process seems to be unfolding in China, which has its "Taobao Villages": clusters of rural enterprises producing everything from red dates to silver handicrafts to children's bicycles.

Taobao is an online marketplace, owned by Alibaba. It's basically just a list of goods and prices.

But perhaps it can aspire to shape society as much as any titan of literature - like Montgomery Ward.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published11 November 2018

- Published2 February 2017