Dresden: The World War Two bombing 75 years on

- Published

The bombing of Dresden created a firestorm that destroyed the centre of the city

"The firestorm is incredible... Insane fear grips me and from then on I repeat one simple sentence to myself continuously: 'I don't want to burn to death'. I do not know how many people I fell over. I know only one thing: that I must not burn."

On 13 February 1945, British aircraft launched an attack on the eastern German city of Dresden. In the days that followed, they and their US allies would drop nearly 4,000 tons of bombs in the assault.

The ensuing firestorm killed 25,000 people, ravaging the city centre, sucking the oxygen from the air and suffocating people trying to escape the flames.

Dresden was not unique. Allied bombers killed tens of thousands and destroyed large areas with attacks on Cologne, Hamburg and Berlin, and the Japanese cities of Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

But the bombing has become one of the most controversial Allied acts of World War Two. Some have questioned the military value of Dresden. Even British Prime Minister Winston Churchill expressed doubts immediately after the attack.

"It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed," he wrote in a memo.

"The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing."

This story contains graphic images.

Dresden is the capital of the state of Saxony. Before the bombing it was referred to as the Florence on the Elbe or the Jewel Box, for its climate and its architecture.

A colour image of Dresden from 1900, showing a number of monuments which were later heavily damaged in the bombing

By February 1945, Dresden was only about 250km (155 miles) from the Eastern Front, where Nazi Germany was defending against the advancing armies of the Soviet Union in the final months of the war.

The city was a major industrial and transportation hub. Scores of factories provided munitions, aircraft parts and other supplies for the Nazi war effort. Troops, tanks and artillery travelled through Dresden by train and by road. Hundreds of thousands of German refugees fleeing the fighting had also arrived in the city.

At the time, the UK's Royal Air Force (RAF) said it was the largest German city yet to be bombed. Air chiefs decided an attack on Dresden could help their Soviet allies - by stopping Nazi troop movements but also by disrupting the German evacuations from the east.

RAF bombers dropped incendiary bombs as well as explosive weapons on German cities to maximise damage

RAF bomber raids on German cities had increased in size and power after more than five years of war.

Planes carried a mix of high explosive and incendiary bombs: the explosives would blast buildings apart, while the incendiaries would set the remains on fire, causing further destruction.

Previous attacks had annihilated entire German cities. In July 1943, hundreds of RAF bombers took part in a mission against Hamburg, named Operation Gomorrah. The resulting assault and unusually dry and hot weather caused a firestorm - a blaze so great it creates its own weather system, sucking winds in to feed the flames - which destroyed almost the whole city.

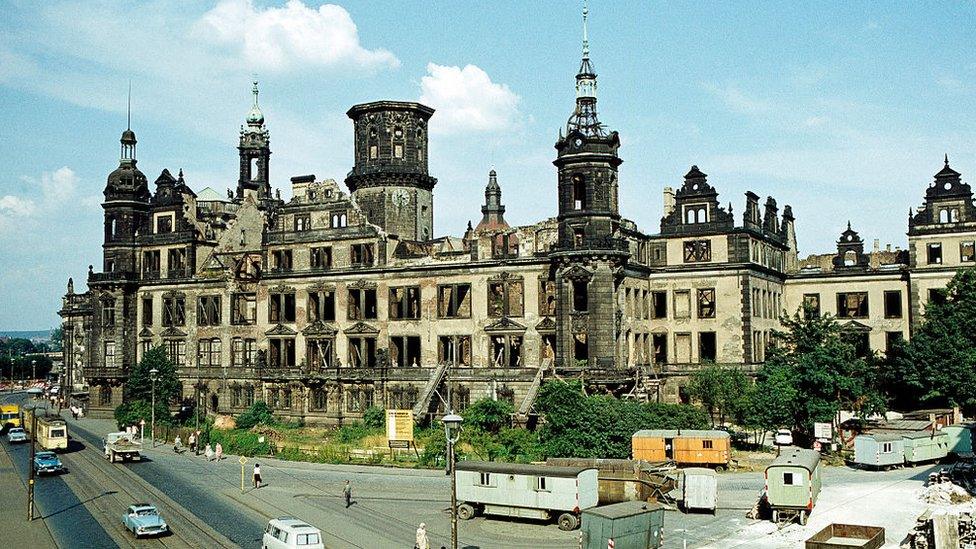

Most of Dresden was destroyed after the British and US attack

The attack on Dresden began on 13 February 1945. Close to 800 RAF aircraft - led by pathfinders, who dropped flares marking out the bombing area centred on the Ostragehege sports stadium - flew to Dresden that night. In the space of just 25 minutes, British planes dropped more than 1,800 tons of bombs.

As was common practice during the war, US aircraft followed up the attack with day-time raids. More than 520 USAAF bombers flew to Dresden over two days, aiming for the city's railway marshalling yards but in reality hitting a large area across the city.

Tens of thousands died, many suffocated in the firestorm

Major landmarks in the city were gutted

On the ground, civilians cowered under the onslaught. Many had fled to shelters after air raid sirens warned of the incoming bombers.

But the first wave of aircraft knocked out the electricity. Some came out of hiding just as the second wave arrived above the city.

People fell dead as they ran from the flames, the air sucked from their lungs by the fire storm. Eyewitness Margaret Freyer described a woman with her baby: "She runs, she falls, and the child flies in an arc into the fire... The woman remains lying on the ground, completely still".

Kurt Vonnegut survived the bombing as a prisoner of war in Dresden.

"Dresden was one big flame. The one flame ate everything organic, everything that would burn," he wrote in his work Slaughterhouse-Five.

He described the city after the attack as "like the moon now, nothing but minerals. The stones were hot. Everybody else in the neighbourhood was dead."

In total, the British lost six bombers in the attack, three to planes accidentally hitting each other with bombs. The US lost one.

The city was a wreck for years afterwards, as seen here, when city dwellers take trams through the ruins in 1946

It took years to clean up the damage

Many parts of Dresden remained as ruins throughout its time as part of East Germany

Nazi Germany immediately used the bombing to attack the Allies. The Propaganda Ministry claimed Dresden had no war industry and was only a city of culture. Though local officials said about 25,000 people had died - a figure historians agree with now - the Nazis claimed 200,000 civilians were killed.

In the UK, Dresden was known as a tourist destination, and some MPs and public figures questioned the value of the attack. A story at the time published by the Associated Press news agency said the Allies were conducting terror bombing, spreading further alarm.

US and UK military planners, however, insisted the attack was strategically justified, in the same way as attacks on other cities - by disrupting industry, destroying workers' homes and crippling transport in Germany.

Dresden's Frauenkirche was rebuilt with the help of donations from the UK and the US after serving as a war memorial for decades

Dresden has recovered since the war, although it still bears the scars

A 1953 US report on the bombing, external concluded that the attack destroyed or severely damaged 23% of the city's industrial buildings, and at least 50% of its residential buildings. But Dresden was "a legitimate military target", the report said, and the attack was no different "from established bombing policies".

The debate about the Allied bombing campaign, and about the attack on Dresden, continues to this day. Historians question if destruction of German cities hindered the Nazi war effort, or simply caused civilian deaths - especially towards the end of the conflict. Unlike an invasion like D-Day, it is harder to quantify how much these attacks helped win the war.

Some argue it is a moral failing for the Allies, or even a war crime. But defenders say it was a necessary part of the total war to defeat Nazi Germany.

It has even become a symbol for conspiracy theorists and some far-right activists - including Holocaust deniers and extremist parties - who have quoted Nazi casualty figures as fact and have commemorated the bombing.

Seventy-five years later, the bombing of Dresden remains a controversial act.

The 100-year-old survivor of Dresden tells BBC Newsday of the 'stupidity of war'

.

- Published10 July 2015

- Published26 September 2018

- Published16 October 2019

- Published13 November 2015

- Published4 February 2020

- Published11 February 2019