How a creative legal leap helped create vast wealth

- Published

Nicholas Murray Butler was one of the leading thinkers of his age: a philosopher, Nobel Peace Prize winner, the president of Columbia University.

In 1911, someone asked Butler to name the most important invention of the industrial era.

Steam, perhaps? Electricity?

"No," he said. They would both "be reduced to comparative impotence" without "the greatest single discovery of modern times" - the limited liability corporation.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

It seems odd to say the corporation was "discovered". But it didn't just appear from nowhere.

Creative legal leap

The word "incorporate" means take on bodily form - not a physical body, but a legal one.

In the law's eyes, a corporation is something different from the people who own it, or run it, or work for it.

And that's a concept lawmakers had to dream up.

Without laws saying that a corporation can do certain things - such as own assets, or enter into contracts - the word would be meaningless.

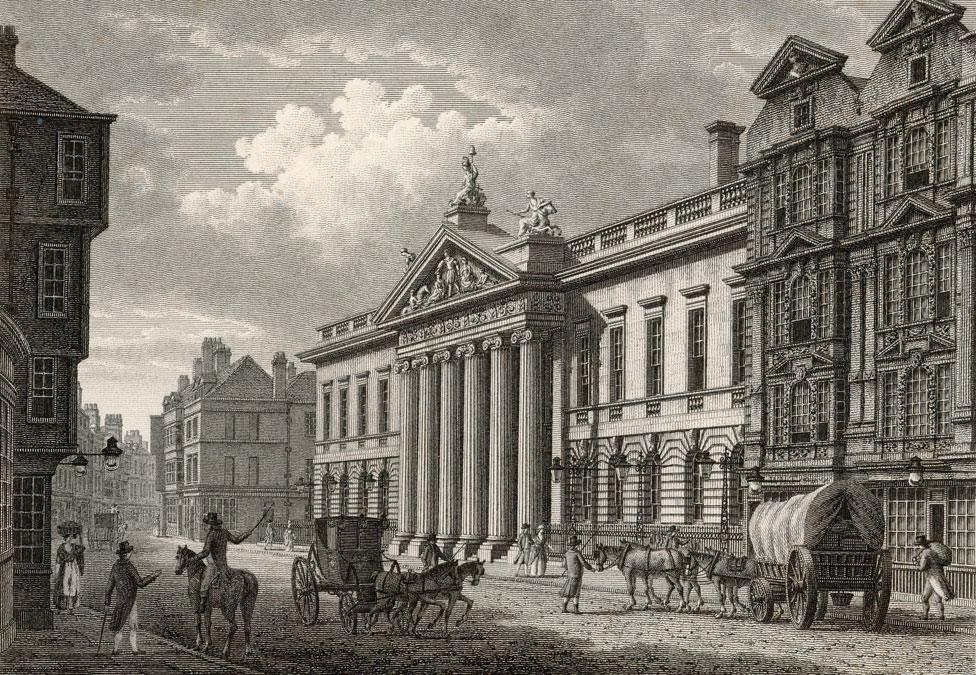

The legal ingredients that comprise a corporation came together in a form we would recognise in England, on New Year's Eve, in 1600.

Back then, creating a corporation didn't simply involve filing in some routine forms - you needed a royal charter.

And you couldn't incorporate with the general aim of doing business and making profits - a corporation's charter specifically said what it was allowed to do, and often also stipulated that nobody else was allowed to do it.

The East India Company's 218 shareholders had limited liability for the company's actions

The legal body created that New Year's Eve was the Honourable East India Company, charged with handling all of England's shipping trade east of the Cape of Good Hope.

Liability liberation

Its shareholders were 218 merchants. Crucially - and unusually - the charter granted those merchants limited liability for the company's actions.

Why was that so important? Because otherwise, investors were personally liable for everything the business did.

If you partnered in a business that ran up debts it couldn't pay, its debtors could come after you - not just for the value of your investment, but for everything you owned.

That's worth thinking about: whose business might you be willing to invest in, if you knew that it could lose you your home, and even land you in prison?

Perhaps a close family member's? At a push, a trusted friend's?

The way we invest today - buying shares in companies whose managers we will never meet - would be unthinkable. And that would severely limit the amount of capital a business venture could raise.

At its peak, the East India Company accounted for about half of the world's trade

Back in the 1500s, perhaps that wasn't much of a problem. Most business was local, and personal. But handling England's trade with half the world was a weighty undertaking.

Over the next two centuries, the East India Company grew to look less like a trading business than a colonial government.

At its peak, it ruled 90 million Indians and employed an army of 200,000 soldiers. It had a meritocratic civil service and issued its own coins.

The East India Company initially used silver coins from the New World, but soon began minting its own currency

Meanwhile, the idea of limited liability caught on.

In 1811, New York state introduced it, not as a royal privilege, but for any manufacturing company. Other states and countries followed, including the world's leading economy, Britain, in 1854.

Industrial growth

Not everyone approved. The Economist magazine was initially sniffy, pointing out that if people wanted limited liability they could agree it through private contracts.

But the limited liability company would prove its worth. The new industrial technologies of the 19th Century needed lots of capital.

A railway company, for example, needed to raise large sums to lay tracks before it could make a penny in profit. How many investors would risk everything on its success? Not many.

Soon, The Economist was gushing that the unknown inventors of limited liability deserved "a place of honour with Watt, Stephenson and other pioneers of the industrial revolution".

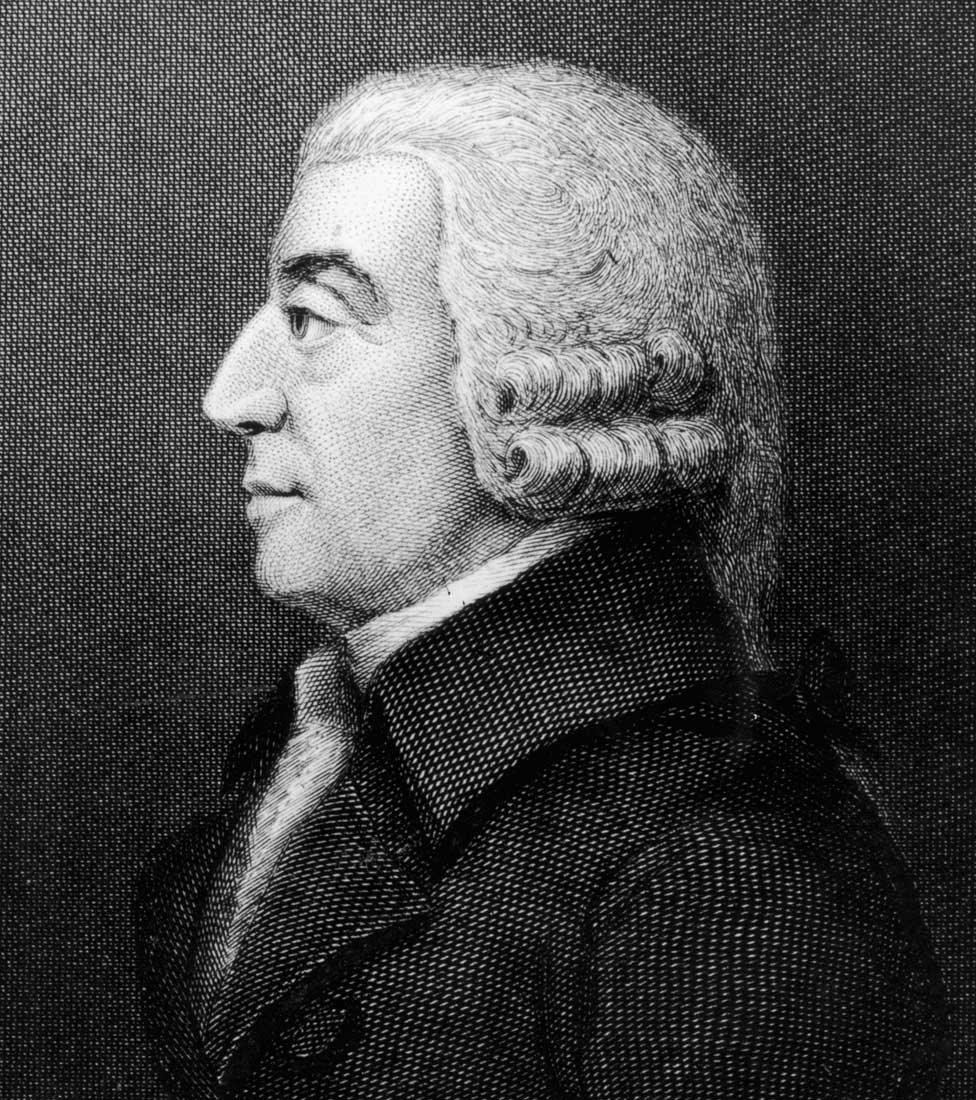

But the limited liability corporation has its problems, one of which was obvious to the father of modern economic thought, Adam Smith.

Adam Smith was sceptical about people looking after money that was not their own

In The Wealth of Nations, in 1776, Smith dismissed the idea that professional managers would do a good job of looking after shareholders' money.

"It cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which partners in a private co-partnery frequently watch over their own," he wrote.

In principle, Smith was right. There's always a temptation for managers to play fast and loose with investors' money.

Maximising profit

We've evolved corporate governance laws to try to protect shareholders, but they haven't always succeeded, as investors in Enron or Lehman Brothers might tell you.

And they generate their own tensions.

Enron's collapse in 2001 was the biggest in US corporate history

Consider the fashionable idea of "corporate social responsibility" - where a company might donate to charity, or decide to embrace higher labour or environmental standards than those stipulated in law.

It can be clever brand-building, and in some cases may result in higher sales. In others, managers may be using shareholders' money to buy social status or a quiet life.

For that reason, the economist Milton Friedman argued that "the social responsibility of business is to maximise its profits". If it's legal, and it makes money, they should do it. And if people don't like it, don't blame the company - change the law.

The trouble is that companies can influence the law, too. They can fund lobbyists. They can donate to electoral candidates' campaigns.

Short-sighted?

The East India Company quickly learned the value of maintaining cosy relationships with British politicians, who duly bailed it out whenever it got into trouble.

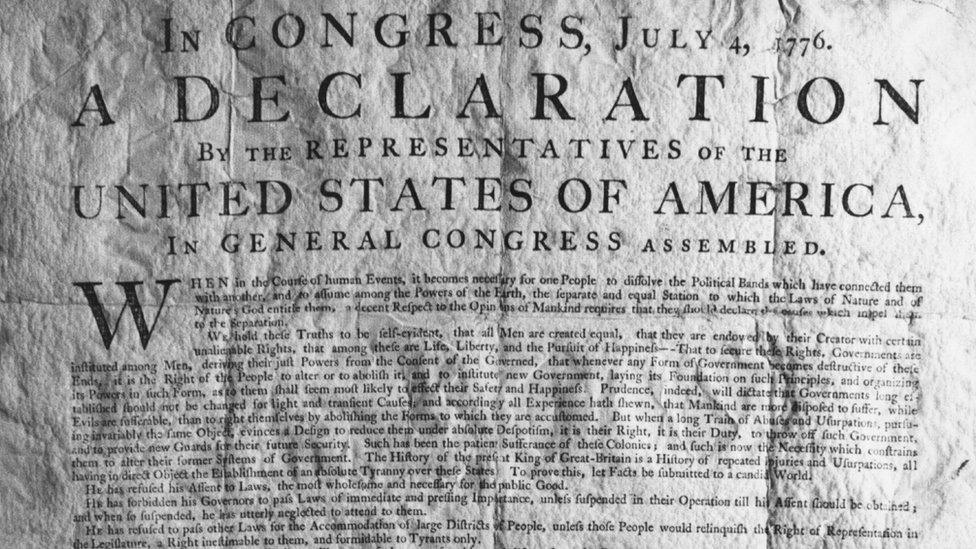

In 1770, for example, a famine in Bengal clobbered the company's revenue. British legislators saved it from bankruptcy, by exempting it from tariffs on tea exports to the American colonies, which was, perhaps, short-sighted on their part: it eventually led to the Boston Tea Party, and the American Declaration of Independence.

Does the United States owe its existence to excessive corporate influence on politicians?

You could say the United States owes its existence to excessive corporate influence on politicians.

And arguably, corporate power is even greater today, for a simple reason: in a global economy, corporations can threaten to move offshore.

When Britain's lawmakers eventually grew tired of the East India Company's demands, they had the ultimate sanction: in 1874, they revoked its charter.

For multinationals with opaque ownership structures, that threat is effectively off the table.

Power of hierarchy

We often think of ourselves as living in a world where free market capitalism is the dominant force. Few want a return to the command economies of Mao or Stalin, where hierarchies, not markets, decided what to produce.

And yet hierarchies, not markets, are exactly how decisions are taken within companies.

When a receptionist or an accounts payable clerk makes a decision, they're not doing so because the price of soy beans has risen. They're following orders from the boss.

More from Tim Harford:

In the US, bastion of free-market capitalism, about half of all private sector employees work for companies with a payroll of at least 500.

Some argue that companies have grown too big, too influential.

In 2016, Pew Research asked Americans if they thought the economic system was "generally fair", or "unfairly favours powerful interests", external. By two to one, unfair won. Even The Economist worries that regulators are now too timid about exposing market-dominating companies to a blast of healthy competition.

But let's not forget what the limited liability company has done for us.

By helping investors pool their capital without taking unacceptable risks, it enabled big industrial projects, stock markets and index funds. It played a foundational role in creating the modern economy.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published4 December 2015

- Published16 April 2015

- Published19 January 2012